NOTE: As with all guest posts, the opinions expressed below are those of the guest author and they do not necessarily represent the views of this blogs administrator and does not represent at all his employer at the Washington Institute for Near East.

Jihadology.net aims to not only provide primary sources for researchers and occasional analysis of them, but also to allow other young and upcoming students as well as established academics or policy wonks to contribute original analysis on issues related to Global Jihadism. If you would like to contribute a piece, please email your idea/post to azelin [at] jihadology [dot] net. Pieces should be no longer than 2,000 words please.

Past Guest Posts:

Behnam Said, “A Brief Look at the History and Power of Anasheed in Jihadist Culture,” May 31, 2012.

Jonah Ondieki and Jake Zenn, “Gaidi Mtaani,” April 24, 2012.

Joshua Foust, “Jihadi Ideology Is Not As Important As We Think,” January 25, 2011.

Charles Cameron, “Hitting the Blind-Spot- A Review of Jean-Pierre Filiu’s “Apocalypse in Islam,” January 24, 2011.

Daveed Gartenstein-Ross, “Why Jihadi Ideology Matters,” January 21, 2011.

Joshua Foust, “Some Inchoate Thoughts on Ideology,” January 19, 2011.

Marissa Allison, “Militants Seize Mecca: Juhaymān al ‘Utaybī and the Siege of the Grand Mosque in Mecca,” June 9, 2010.

—

By Kévin Jackson

Defining al Qa’ida’s membership has always represented a divise issue among analysts. I’ll approach this topic by focusing on a fundamental practice commonly used by jihadi organizations, namely vowing an oath of allegiance or bay’a.

In a nutshell, the bay’a procedure constitutes the cornerstone defining one’s membership. A longstanding ritual featuring in the early Islamic tradition, giving bay’a (individually or collectively) consists in recognizing the legitimacy of a group/state leader authority. The covenant between the amir (leader) and the one who gives the bay’a lies in listening and obeying, in hard and easy times, as long as the amirship follows the right path. Rendering allegiance to the amir of al Qa’ida, for example, would thus imply not to dispute his and/or al Qa’ida’s commanders’ directives and to fully support the organization’s agenda.

The Bay’a has been institutionalized within the jihadi milieu for the doctrinal foundations it acts upon stress the mandatory aspect of such a practice. Given that joining a jama’ah (group) of mujahidin is seen as an obligation (wajib) upon every Muslim and cannot be done except with a pledge of allegiance, the bay’a is thus considered as such too. From an organizational perspective, these doctrinal regulations secure the loyalty and cohesion within the ranks, while preventing core attrition by tightly binding new recruits through a formal covenant.

It is worthwhile underlining the contractual aspect of this longstanding ritual drawing lines of demarcation between jihadi organizations. If the one giving the oath promises to listen and obey whatever the hardships, the one receiving it is also entitled to fulfill his obligations as the amir. This counterpart from the leader amounts to a continuous commitment to respect the covenant provisos and serve the interests of Islam and Muslims through the policy he implements. The amirship also requires certain characteristics, which, for al Qa’ida, revolve around knowledge, experience, ethical qualities, etc.

On the other hand, a bay’a has to be accepted before one can be considered as a sworn member/organization. This decision falls upon the amir‘s goodwill and depends on the extent to which would-be comers meet the required criteria prescribed by the organization leadership. As a result, groups rendering their allegiance to Ayman al Zawahiri cannot be labeled al Qa’ida in the absence of an official recognition from the Pakistan-based leadership. This explains why assertions dubbing some al Qa’ida’s affiliates/franchises on the only basis that an oath has been sworn should be met with skepticism at the very least.

For example, while Harakat al Shabab al Mujahidin had pledged their loyalty to Usama bin Ladin in September 2009, the Somali group couldn’t be portrayed as being part of al Qa’ida without any further confirmation by the mothership in the Pakistan’s tribal areas. This changed only after February 2012, following a joint statement of Ayman al Zawahiri (amir of al Qa’ida) and Mukhtar Abu’l Zubayr (amir of al Shabab), where the Egyptian officially accepted al Shabab under al Qa’ida’s direction. This is the type of acknoweldgement which should be looked at to draw accurate distinctions between jihadi factions.

A cherished autonomy

Well-understood by jihadis, the binding burden of the oath can be sensed through the lens of militants’ own trajectory. The life story of Khalid Shaykh Muhammad (KSM) is a case in point. Even after having moved to Kandahar to work directly with al Qa’ida’s leadership in the late 1990’s, the 9/11 mastermind was still reluctant to formally join. Translation: while he had decided to play on al Qa’ida’s team via close work relationships, he was still refusing to swear allegiance to bin Ladin so as to maintain his operational room for manoeuvre. KSM became a core member only after 9/11 attacks were carried out, following pressures from his peers arguing that the persistent refusal of someone with his pedigree would establish a worrisome precedent for others.

Given how the pledge of allegiance undermines one’s autonomy, it should not come as a surprise that others have shared KSM’ sentiments by postponing the bay’a as long as they could or simply rejected it.

Before bin Ladin formally declared Mulla Muhammad Umar as his direct leader, the Saudi and his entourage made their best to avoid this option to ensure a complete freedom to their global jihad. Notwithstanding external pressures and an increased tense context, the late amir of al Qa’ida still kept using pretexts to shelve a proposal put forward by Abu’l Walid al Misri, a respected senior Egyptian mujahid, designed to improve his relationship with the Afghan Taliban leader. Bin Ladin eventually resigned himself to perform the bay’a in late November 1998 but (and this is a big one) only through Abu’l Walid acting as his proxy. The indirect oath would enable bin Ladin to play it both ways according to the circumstances and as a result, despite being virtually tied by his pledge, still retain his independence. And indeed, the following years, bin Ladin continued to by-pass Mulla Umar’s instructions, namely stopping his media campaign and external operations against the US.

Also instructive is Abu Jandal’ story, which outlines another way of keeping one’s room for manoeuvre. The Yemeni, along with some of the group of combatants he came with, vowed allegiance to bin Ladin after a three-day meeting with the al Qa’ida’s leader in Jalalabad in 1997. Except that it was not an integral but a conditional one. Hence, while Abu Jandal had accepted bin Ladin as his leader in Afghanistan, the deal was that he will not take his orders from the Saudi should he be in another battlefield. Later in 1998, the then bin Ladin’s bodyguard decided that the time has come and eventually pledged an unconditional oath, thereby making him a core member of al Qa’ida.

Muhammad al Owhali’s interrogation provides a further insightful glimpse into the meaning of the bay’a in terms of command and control, as well as the wariness it provokes among some. The 1998 East Africa bombing operative told his FBI interrogators that his refusal to formally join al Qa’ida, despite having been urged to do so, was linked to his fear that, once a core member, he might end up working in non-military activities while having a strong desire in armed jihad. His non-membership would thus enable him to accept or refuse a mission assigned to him by al Qa’ida’s leaders/ commanders according to his own will. As put it in his interrogation: « Once you take the bayat you no longer have a choice in what your missions would be. »

Theses various episodes clearly outline the concrete implications of pledging an oath of allegiance and also explain jihadis’ lack of promptness in giving it. Not

Search Results for: gaidi mtaani

GUEST POST: A Brief Look at the History and Power of Anasheed in Jihadist Culture

NOTE: As with all guest posts, the opinions expressed below are those of the guest author and they do not necessarily represent the views of this blogs administrator and does not represent at all his employer at the Washington Institute for Near East.

Jihadology.net aims to not only provide primary sources for researchers and occasional analysis of them, but also to allow other young and upcoming students as well as established academics or policy wonks to contribute original analysis on issues related to Global Jihadism. If you would like to contribute a piece, please email your idea/post to azelin [at] jihadology [dot] net. Pieces should be no longer than 2,000 words please.

Past Guest Posts:

Jonah Ondieki and Jake Zenn, “Gaidi Mtaani,” April 24, 2012.

Joshua Foust, “Jihadi Ideology Is Not As Important As We Think,” January 25, 2011.

Charles Cameron, “Hitting the Blind-Spot- A Review of Jean-Pierre Filiu’s “Apocalypse in Islam,” January 24, 2011.

Daveed Gartenstein-Ross, “Why Jihadi Ideology Matters,” January 21, 2011.

Joshua Foust, “Some Inchoate Thoughts on Ideology,” January 19, 2011.

Marissa Allison, “Militants Seize Mecca: Juhaymān al ‘Utaybī and the Siege of the Grand Mosque in Mecca,” June 9, 2010.

—

By Behnam Said

At the moment, I am working on my PhD-project on “Militant hymns (anasheed jihadiya) as a part of the Jihadist culture”. This culture I consider to be more effective in terms of propaganda and social cohesion than any ideology alone could be. Young radicals all over the world are listening to the nasheeds extensively – a fact, authorities are getting more and more aware of, as court papers and other sources show. Some of the most interesting findings (which are actually a lot) I will outline in an article to be published in November for Studies in Conflict and Terrorism. Until then Aaron gave me the opportunity to share at least some facts with the readers of “Jihadology” in advance.

Background

Nasheeds, as you all are aware of, are an integral part of almost every Jihadist video production. For example, we see al-Qaeda members in action on the battlefield accompanied by the soundtrack of a smooth a cappella song. On relevant internet forums and websites you will find a bulk of these nasheeds as mp3-files, sometimes even complete collections. There are also plenty of videos with these songs on YouTube. It appears as if no Jihadist can establish his YouTube channel without posting at least a few militant hymns. On Facebook there are also groups publishing militant nasheeds that obtain more than 10,000 “likes”.

Not all of the songs which are popular in the Jihadist scene are new. Many of them are based on songs which were included in the songbooks of the 1980s and in poems of the so called shu´ara ad-da´wa, a branch of poetry which began in the 1950s and ended approximately in the 1980s. For example one of the most popular songs at the moment is “Bi-Jihadina”, which is actually a song by Abu Mazin, a popular Syrian munasheed, who recorded it either in the late 70s or the early 80s. There is also one example of a song used in videos of the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) based on a poem by Muhammad Iqbal (1877-1938), the famous Pakistani poet, that has been translated to Arabic. Some other nasheeds, like the Somali ash-Shabab song “Rayatu t-Tauhid” or some AQAP songs, are contemporary.

The fascination of these songs is described by Samir Khan, the former editor of Inspire, in an article for Inspire:

I remember when I traveled from San´a, for what seemed like years, in a car to one of the bases of the mujahidin, the driver played this one nashīd repeatedly. It was “Sir ya bin Ladin”. I already knew of this nashīd from before, but something had struck me at that moment. The nashīd repeated lines pertaining to fighting the tyrants of the world for the purpose of giving victory to the Islamic nation. But it also reminded the listener that Shaykh Usama bin Ladin is the leader of this global fight. I looked out of the window at the tall mud houses below the beautiful sky and closed my eyes as the wind blew through my hair.”

This personal experience by Khan finds its equivalent in many theoretical descriptions of the desired effects of nasheeds on young people. The oldest sources in this context I found in some nasheed collections from the 1980s. Here it is clearly said, that nasheeds are an instrument to awaken the wish for martyrdom and self sacrifice in the hearts of young Muslims and to give them strength for da´wa and Jihad.

You can categorize nasheeds in accordance with the topics they cover. Often you will find that the poems fit into categories of classical poetry, for example:

- Mourning songs

- Praising songs

Other categories are more modern:

- Prisoners songs

- Songs regarding ongoing political processes (for example the battle for Syria)

- Palestine songs

But most of the songs I analyzed can be described as “battle songs”. Focusing on war and ones fighting group, which is described as heroic and brave in antipode to the tyrannical and oppressive enemy (taghut). Here I am not sure if such hymns can be described as classical by category, because the language of such songs are very Jihadist.

Legality and Influence

It is also interesting to have a look at the different legal stances towards nasheeds, especially from Salafi and Wahhabi scholars. I was surprised to find most of them skeptical towards nasheeds. They consider them allowed (mubah), but only under strict conditions regarding form (a cappella only) and content (purely Islamic and Jihad-supportive). So I tried to figure out why the Jihadists are making use of nasheeds so extensively even though Salafi and even more Wahhabi scholars underline the importance of limiting listening to nasheeds. The answer, I think, lies in the history of the nasheeds, which I mentioned above. Modern nasheeds have their origin with the Muslim Brotherhood (MB) and its radical branches in the Levant and in Egypt. From here they made their way to the Arabian Peninsula where nasheeds were known at least from the 70s on, but became more popular in the early 90s during the sahwa-period as sources underline. The stance of MB ideologues was always more positive towards music than that of the Wahhabis and Salafis. Nasir ad-Din al-Albani for example criticized articles from the 50s published in the MB magazine which called for “Islamic music”, which he called as absurd as “Islamic Communism”. So the addiction of Jihadis to nasheeds reflects the influence of the MB on the militant movement. The only clear influence on nasheeds by the Salafis/Wahhabis is the Jihadist adoption of the strict prohibition of any music instruments, except the use of hand drums in some cases.

The Jihadist culture thus is – like the movement itself – a merging of MB and Salafi/Wahhabi ideology. But in this case the MB influence is absolutely overwhelming and it shows that the culture of the MB and its militant branches is more crucial for the Jihadis than some might assume.

I hope that I hereby provided you some input for discussions about the history of Jihadism and its culture as well as about the relevance of this culture.

Behnam Said has studied Islamic Science, Political Science, and History in Hamburg, Germany. His main fields of interest are the relation of Sunna and Shia, history and culture of modern Afghanistan, and political and militant Islamism. Beside his current job as an intelligence analyst he is doing his PhD at the University of Jena on the topic of militant nasheeds. A more in depth version of this post will be published in a forthcoming issue of the academic journal “Studies in Conflict and Terrorism.”

Articles of the Week – 4/21-4/27

Sunday April 22:

On Reading Zawahiri – Marisa Urgo, Making Sense of Jihad: https://bit.ly/Jpx8e9

Examining Gaidi Mtaani, Al-Qaida Swahili-language magazine Issue 1 – Aaron Weisburd, Internet Haganah: https://bit.ly/I6S7C8

Al-Qaida Advises the Arab Spring: Egypt – Joas Wagemakers, Jihadica: https://bit.ly/Ixx3SB

Another day, another dead al Qâ’idah leader – Mr. Oranges’ War Tracker: https://bit.ly/I2zhcM

AUMF and Yemen – Gregory Johnsen, Waq al-Waq: https://bit.ly/JrzF6n

More on Islamist Performance in Algeria – Kal, The Moor Next Door: https://bit.ly/I4NKHY

Monday April 23:

North Caucasus Insurgency Leader Predicts ‘Results’ From Spring Offensive – Liz Fuller, Caucasus Report: https://bit.ly/I4NPeK

Knowing what you’re doing – Gregory Johnsen, Waq al-Waq: https://bit.ly/JrAKLh

Boko Haram Escalates Attacks on Christians in Northern Nigeria – David Cook, CTC Sentinel: https://bit.ly/JrAMCW

French Counterterrorism Policy in the Wake of Mohammed Merah’s Attack – Pascale Combelles Siegel, CTC Sentinel: https://bit.ly/IkQiAs

Revisiting Shaykh Atiyyatullah’s Works on Takfir and Mass Violence – Christopher Anzalone, CTC Sentinel: https://bit.ly/HWi2ZE

Taking the Place of Martyrs: Afghans and Arabs under the Banner of Islam – Darryl Li, Arab Studies Journal: https://bit.ly/Ib044R

Locating the Secular in Sayyid Qutb – Mohammad Salama and Rachel Friedman, Arab Studies Journal: https://bit.ly/Ib044R

Tuesday April 24:

Reply Delete Favorite · OpenCombating Terrorism in the New Media Environment – John Curtis Amble, Studies in Conflict & Terrorism: https://bit.ly/Ipueo7

Cooking the Books: Strategic Inflation of Casualty Reports by Extremists in the Afghanistan – Chris Lundry, Steven R. Corman, R. Bennett Furlow & Kirk W. Errickson, Conflict Studies in Conflict & Terrorism: https://bit.ly/K5zo5e

Analysis of Jihadi Terrorism Incidents in Western Europe, 2001–2010 – Javier Jordan, Studies in Conflict & Terrorism: https://bit.ly/K5ztpt

In short supply: The Britain-Pakistan jihadist trade flow – Raffaello Pantucci, The AfPak Channel: https://bit.ly/I8MNPt

Gaidi Mtaani – Jonah Ondieki and Jake Zenn, Jihadology: https://bit.ly/InjTIN

Wednesday April 25:

“Mystery solved” on the oldest member of al Qa’ida – Kévin Jackson, All Eyes on Jihadism: https://bit.ly/JBIoVL

Guest Posts

Jihadology.net aims to not only provide primary sources for researchers and occasional analysis of them, but also to allow other young and upcoming students as well as established academics or policy wonks to contribute original analysis on issues related to Global Jihadism. If you would like to contribute a piece, please email your idea/post to azelin [at] jihadology [dot] net.

Past Guest Posts:

Andrew Zammit, “Making Sense of Alleged AQAP-Houthi Cooperation: Local Pragmatism or Further Accommodation Between al-Qaeda and Iran?,” February 17, 2025.

Intel Cocktail, “SoundCloud’s ISIS Problem and How to Fix It,” July 24, 2023.

Kévin Jackson, “al-Zawahiri’s Line of Succession,” June 26, 2023.

Saleh al-Hamawi, “Intellectual Differences Between the Taliban, al-Qaeda, ISIS, and the Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham,” October 27, 2021.

Daveed Gartenstein-Ross and Madeleine Blackman, “Fringe Fluidity: How Prior Extremist Involvement Serves as a Distinct Radicalization Pathway,” February 28, 2019.

Nathan Vest, “Heretics, Pawns, and Traitors: Anti-Madkhali Propaganda on Libyan Salafi-Jihadi Telegram,” February 25, 2019.

Reinier Bergema and Colonel RNLAF (ret.) Peter Wijninga, “Coming Home: Explaining the Variance in Jihadi Foreign Fighter Returnees Across Western Europe,” February 15, 2018.

Abdulbasit Kassim, “‘Who Is a Muslim?’: Mubi Mosque Attack, Masjid ad-Ḍirār, and the Historical Attempt at Defining a Muslim in the 19th, 20th and 21st Century Hausaland and Bornu,” November 21, 2017.

Alexander Schinis, “Hymnal Propaganda: A Closer Look at ‘Clanging of the Swords’,” Octover 16, 2017.

Héni Nsaibia, “Jihadist Groups In The Sahel Region Formalize Merger,” March 27, 2017.

Amarnath Amarasingam, “An Interview with Rachid Kassim, Jihadist Orchestrating Attacks in France,” November 18, 2016.

Amarnath Amarasingam, “Searching for the Shadowy Canadian Leader of ISIS in Bangladesh,” August 2, 2016.

Aymenn al-Tamimi, “The Fitna in Deraa and the Islamic State Angle,” March 26, 2016.

Christopher Anzalone, “From al-Shabab to the Islamic State: The Bay‘a of ‘Abd al-Qadir Mu’min and Its Implications,” October 29, 2015.

Cori E. Dauber and Mark Robinson, “ISIS and the Hollywood Visual Style,” July 6, 2015.

Dur-e-Aden, “TTP Says That Baghdadi’s Caliphate Is Not Islamic—But Is Anyone Listening?,” June 29, 2015.

North Caucasus Caucus, “The Conquest of Constantinople: The Islamic State Targets a Turkish Audience,” June 9, 2015.

Sam Heller, “Ahrar al-Sham Spiritual Leader: The Idol of Democracy Has Shattered,” June 3, 2015.

Asher Berman, “The Syria Twitter Financiers Post-Sanctions,” May 18, 2015.

Sam Heller, “Abdullah al-Muheisini Weighs in on Killing of Alawite Women and Children,” May 12, 2015.

Maxwell Martin, “A Strong Ahrar al-Sham Is A Strong Nusra Front,” April 7, 2015.

Aimen Dean, “The End of al-Qaeda,” April 4, 2015.

Amarnath Amarasingam and Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi, “Is ISIS Islamic, and Other “Foolish” Debates,” April 3, 2015.

Charlie Winter, “Women of The Islamic State: Beyond the Rumor Mill,” March 31, 2015.

Anne Stenersen and Philipp Holtmann, “The Three Functions of UBL’s “Greater Pledge” to Mullah Omar (2001-2006-2014): Attract Jihadi Volunteers, Legitimize the Taliban as Guardians of the Caliphate and Denounce IS-leader al-Baghdadi,” January 8, 2015.

Sam Heller, “Muhammad al-Amin on Ahrar al-Sham’s Evolving Relationship with Jabhat al-Nusrah and Global Jihadism,” December 9, 2014.

Philipp Holtmann, “The Different Functions of IS Online and Offline Plegdes (bay’at): Creating A Multifaceted Nexus of Authority,” November 15, 2014.

Sam Heller, “Recriminations on Social Media Shed Light on Jabhat al-Nusrah’s Inner Workings,” November 4, 2014.

Sam Heller, “Jeish al-Muhajireen wal-Ansar Shar’is Debate Islamic Rule Inside and Outside the ‘Islamic State’,” October 25, 2014.

Goha’s Nail, “Manbij and The Islamic State’s Public Administration,” August 27, 2014.

Daveed Gartenstein-Ross and Oren Adaki, “Ansar al-Sharia in Tunisia’s Social Media Activity in 2014,” June 6, 2014.

Zach Goldberg, “Damned if They Do, Damned if They Don’t: The Gordian Knot of Europe’s Jihadi Homecoming,” April 22, 2014.

Daveed Gartenstein-Ross, “Ayman al-Zawahiri on Jihadist Infighting and the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham,” April 21, 2014.

Joel D. Parker, “Ahrar al-Sham versus Ahrar al-Sham: The band and the militia,” January 29, 2014.

Daveed Gartenstein-Ross, “Abdulhakim Mujahid Muhammad (Carlos Bledsoe): A Case Study in Lone Wolf Terrorism,” December 23, 2013.

Hazim Fouad, “Salafi-Jihadists and non-jihadist Salafists in Egypt – A case study about politics and methodology (manhaj),” April 30, 2013.

Daveed Gartenstein-Ross and Tara Vassefi, “Perceptions of the “Arab Spring” Within the Salafi-Jihadi Movement,” November 19, 2012.

Jack Roche, “The Indonesian Jamā’ah Islāmiyyah’s Constitution (PUPJI),” November 14, 2012.

Kévin Jackson, “The Pledge of Allegiance and its Implications,” July 27, 2012.

Behnam Said, “A Brief Look at the History and Power of Anasheed in Jihadist Culture,” May 31, 2012.

Jonah Ondieki and Jake Zenn, “Gaidi Mtaani,” April 24, 2012.

Joshua Foust, “Jihadi Ideology Is Not As Important As We Think,” January 25, 2011.

Charles Cameron, “Hitting the Blind-Spot- A Review of Jean-Pierre Filiu’s “Apocalypse in Islam”,” January 24, 2011.

Daveed Gartenstein-Ross, “Why Jihadi Ideology Matters,” January 21, 2011.

Joshua Foust, “Some Inchoate Thoughts on Ideology,” January 19, 2011.

Marissa Allison, “Militants Seize Mecca: Juhaymān al ‘Utaybī and the Siege of the Grand Mosque in Mecca,” June 9, 2010.

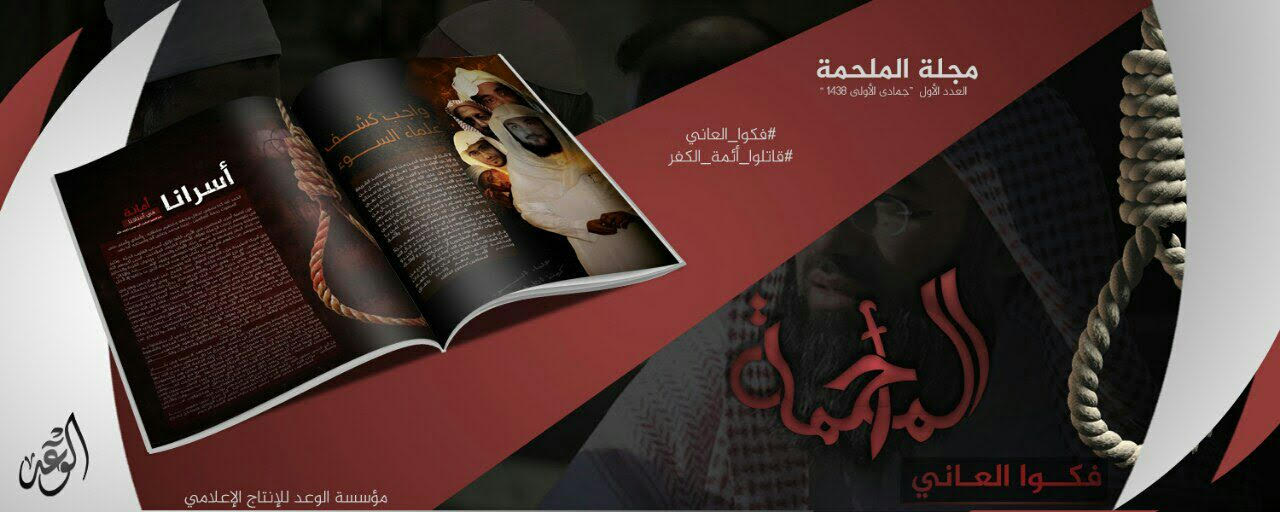

New magazine released: "al-Malḥamah Issue #1"

Click the following link for a safe PDF copy: al-Malḥamah Magazine Issue #1

_____________

To inquire about a translation for this magazine issue for a fee email: [email protected]