NOTE: As with all guest posts, the opinions expressed below are those of the guest author and they do not necessarily represent the views of this blogs administrator and does not at all represent his employer at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy.

Jihadology.net aims to not only provide primary sources for researchers and occasional analysis of them, but also to allow other young and upcoming students as well as established academics or policy wonks to contribute original analysis on issues related to jihadism. If you would like to contribute a piece, please email your idea/post to azelin [at] jihadology [dot] net.

Click here to see an archive of all guest posts.

—

TTP Says That Baghdadi’s Caliphate Is Not Islamic—But Is Anyone Listening?

By Dur-e-Aden

On June 15, 2015, the Taliban in Pakistan released a 66 page document in Urdu detailing why Baghdadi’s caliphate is not Islamic. While organized in the form of an academic paper, with a central thesis and scholarly citations, the document itself is hastily written and is an exercise in repetition. Nevertheless, it gives a glimpse into the strategic thinking of TTP, and indicates that they feel threatened enough by Baghdadi to release this statement.

The introductory paragraphs discuss the time of the Prophet, and contrasts Baghdadi’s actions against it. For example, when the Prophet was militarily weak in Mecca, he did not break any idols in the Kaaba since this would have opened up a war on multiple fronts. Moreover, he did not kill those hypocrites who claimed to be Muslims but were actually enemies of Islam, as people would have accused him of killing his friends and starting a civil war. In short, he was a pragmatic military strategist, and doing so didn’t entail that he was giving in to the kuffar (infidels). Today, the Taliban in Afghanistan and Pakistan see themselves as following this path by only fighting the occupying forces, while both Hanafi and Salafi Muslims reside on this land. However, ISIS’s actions against other Muslims, especially in the Nangahar province, from the Taliban’s perspective is benefitting the enemies of Islam.

The document then lists 24 reasons laced with religious references, both from the Islamic history of different caliphates, as well as the opinions of various Salafi and non-Salafi scholars. The central theme is that a caliph cannot be appointed without the consensus of the majority of the Umma. In the case of Baghdadi, neither the majority of the Muslim Umma, nor the majority of the Jihadi Umma, have pledged allegiance to him. The document lists examples of people such as Mullah Omar, Ayman al-Zawahiri, Abu Mohammad al-Maqdisi, Abdollah Mohsini, Abu Qatada al-Falasteeni, as well as emirs of Al-Shabaab, AQAP, and South-east Asian militant groups, whose lack of support has rendered his caliphate to be invalid. Finally, even if Baghdadi claims to be elected by a Shura of representatives, how can a caliph that is supposed to be the leader of Muslims worldwide be selected only by a regional Shura?

The document goes on to discuss certain responsibilities of a caliph that Baghdadi is not equipped to carry out. For example, a caliph is supposed to defend all Muslims and create conditions where they can live in peace. However, considering that Baghdadi himself is in involved in war, how can he protect Muslims worldwide, from Xinjiang to Morocco, who are embroiled in different conflicts? Furthermore, a caliph has to be involved in the day to day affairs of his people such as resolving disputes, collecting zakat from the rich to give to the poor, and making people follow Sharia. Baghdadi on the other hand, can’t even appear in public. While talking about these issues, the document refers to a Prophet’s saying, which states that “Both me (the Prophet) and God curse him who forcefully imposes his rule without the consent of the Muslims.”

The final part of the document challenges specific interpretations of ISIS with regards to the primary Islamic sources. TTP argue that all the “misguided” sects throughout history have quoted the texts to justify their ideological positions. For example, Mu’tazila believe that Quran is a created book because God says in the Quran that “God created everything.” Similarly, Barelvis claim that Prophet is present everywhere because Quran mentions, “And among you is his Messenger.” However, the TTP argues, these interpretations are still wrong. Therefore, when Baghdadi quotes the hadith which urges Muslims to pledge allegiance to their caliph or they would die in ignorance, it does not refer to his caliphate. It only refers to the caliphate of a specific Imam who is appointed according to Sharia, and whose appointment fulfills all the conditions of the bayah. As we (the TTP) have shown, that is not the case.

But is this document going to be effective in persuading people to not join ISIS? It is very unlikely. As both Graeme Wood and Hassan Hassan have argued, one of the important characteristics of ISIS’s ideology is that it is anti-clerical. Hence, going against centuries of established Islamic traditions, and directly to the text of Quran and the Hadith gives them a certain purity. As a result, when others claim that ISIS is not Islamic, they are not only immune to this messaging, but actually enjoy it. ISIS refers to the Prophet’s hadith which states that during the end of times, there will be 73 sects of Muslims, and only one of them will be the true one. Seeing so many other Muslim sects united against them actually proves their point. Therefore, when it comes to the new generation of jihadists, even those in Afghanistan and Pakistan can get motivated by ISIS’s peculiar religious ideology, accompanied by a winning narrative, illusions of grandeur, and a promise to be part of an historical project.

However, because Pakistan in particular has a plethora of jihadist groups, their core members are unlikely to shift their allegiance to ISIS, especially if they have fought for a particular cause for a long time (e.g. against India, against Coalition forces in Afghanistan, against Pakistani state etc.), and that cause has become central to their identity. Being part of a coherent organizational structure increases the likelihood that those members are clearheaded of what their short term goals are, and being part of a worldwide caliphate doesn’t appear near the top of their lists.

Finally, while this is true that some of the defectors from these established groups, such as the TTP itself, have pledged allegiance to ISIS; it should be noted that those members defected at a time when they were dissatisfied with their positions in the existing organization, and the organization was going through infighting. In other words, there might be an underlying opportunistic motivation for their defection, as opposed to an ideological one. Not to mention that Taliban comes from a Deobandi tradition within Islam, which is distinctive from the Salafist background of ISIS. This can spell good and bad news for ISIS. The good news is that they have helped ISIS in establishing a presence in the Af-Pak region. The bad news is that opportunistic fighters are more likely to accelerate the divisions within ISIS’s ranks as well, as they compete for money and power (the reasons that they left their previous organizations for). Moreover, they are more likely to neglect or disobey ISIS’s orders over the long run, especially if the ideological commitment to ISIS’s cause is absent.

Therefore for now, as far as this document goes, TTP might be preaching to an already convinced audience.

Dur-e-Aden is a PhD student at University of Toronto where her research focuses on rebel recruitment within Islamist insurgent organizations. She holds a MA in Political Science from University of British Columbia, and tweets @aden1990.

Search Results for: but if they fight you

The Clear Banner: From Paradise Now To Paradise Hereafter: Maldivian Fighters In Syria

The Clear Banner sub-blog on Jihadology.net is primarily focused on Sunni foreign fighting. It does not have to just be related to the phenomenon in Syria. It can also cover any location that contains Sunni foreign fighters. If you are interested in writing on this subject please email me at azelin [at] jihadology [dot] net.

—

From Paradise Now To Paradise Hereafter: Maldivian Fighters In Syria

By Dr. Azra Naseem

The young man was on his way to school when Ali Adam first saw him. He was a high achiever; among national Top Ten in the GCE O’Level examinations1. Every day after school the young man worked in a shop. That’s where Adam met him next. Slowly, Adam cultivated a relationship with him until he became a close friend. This is when Adam’s real work began.

Everyday the two friends met. They discussed religion. Adam always started the discussions with stories about the plight of Muslims living in countries like Palestine, Pakistan, Yemen and Syria. The stories were meant to arouse the young man’s sympathies. When they ended, the young man understood ‘Jihad is a duty.’ Half of Adam’s work was done.

About six months later, Adam began the second phase of his work: to take the young man as far as Pakistan. Adam first accompanied him to India. The young man’s parents cried, begged him not to go. Their pleas fell on deaf ears. The young man’s sister was a student in India; she, too, decided to go with him. He wanted to take another woman with him. Adam only agreed on condition the young man married her. About five people were gathered together and a wedding was quickly performed.

“When we got to Pakistan, a Lashkar–e–Taiba agent said the marriage was not valid. We were told to return home. I came to Male’. The young man’s sister went back to study in India. He stayed in Pakistan for about five years, doing odd jobs,’ Adam said, when asked what the most memorable events in his story were.

Adam says he is a recruiter who finds Maldivians to fight in Syria. About a year ago, he ‘saw the errors of his ways’ and stopped the work. He described his job, and that of his co-workers, as operating within ‘a major network’. It is an endless task, beginning with collecting funds and recruiting people in the Maldives.

[…]

The recruitment work is done in parallel with procuring finance. Adam described the recruitment process step by step: sermons that encourage ‘Jihad’ are given in mosques like Dharumavantha Mosque where people hold the Friday prayers in a separatist congregation [away from the mainstream mosques]. Some people travel to outer islands on the pretext of teaching Quran recitation and providing religious counselling. Envoys are also sent to Maldivian students in countries like Sudan, Egypt and Yemen to enlist their support. They look for people ‘who can be easily convinced’, and seek to ‘play with their minds’.

According to Hussein Rasheed, who was arrested at Male’ airport en route to Syria, Maldivian fighters travel to Syria via Sri Lanka, India or Thailand – all popular travel destinations with Maldivians. The would-be fighters stopover at these destinations [for varying lengths of time] before travelling to Turkey to cross the border into Syria. That’s when ‘Jihad’ begins. They don weapons, and carry out suicide attacks.

‘I know 15 to 20 Maldivians who are in Syria right now. This includes a woman, too. Some Maldivian students who had been studying in Egypt, Sudan and Yemen lead these fighters. One of them has a family in Syria, including a baby. All Maldivians are fighting with Al-Qaida affiliated Jabhat Al-Nusra’, Rasheed said.

What type of Maldivian goes to Syria? Do any of them want to return to Maldives? What happens to their families [in Syria] if one of them dies in battle? All questions.

‘I know that among the fighters are people who have been convicted and sentenced in relation to the Himandhoo case and in connection with the Sultan Park bombing. I don’t think anyone who went there has returned. I doubt any would. If one of them dies, someone else will marry his [the deceased man’s] widow. Expenses will also be looked after, and money given,’ Rasheed, who was arrested last year, said in answer to those questions.

[…]

The above text is a translation of an article in Maldivian daily newspaper, Haveeru, published on 4 June 2014, shortly after the first Maldivian died fighting in Syria2. It serves as an introduction to a growing problem confronted by Maldives – a steady increase in the number of people leaving for ‘Jihad’ in Syria.

Background

Officially, the Maldives is a ‘100% Muslim’ country. The state religion is Islam, and its constitution stipulates every citizen must be a Muslim. Only a Sunni Muslim can be President, or become a judge. Despite what the legal stipulations may suggest, for centuries Islam in Maldives has been fundamentally different from the strict, fundamentalist Islam practised in some ‘Islamic states’. Both the island culture and the centuries old pre-Islamic Buddhist history, as well as its remote geography and distance from the ‘Islamic world’ leant itself to the evolution of an Islam that, while adhering to the five basic tenets of the religion, reflected few of the common practises and jurisprudence followed by other ‘100% Muslim’ countries. This, however, changed drastically in the 21st Century, especially after the United States-led War on Terror began. With seemingly unlimited funding from Islamist societies and organisations—mostly Saudi Arabia—Islam that follows the teachings of ‘Revolutionary Islamism’3 has become predominant, side-lining the country’s Traditionalist Islamic practises with astounding success4.

Dying in Syria

Figure 1. Abu Turab (L) first Maldivian known to have died fighting in Syria

The first Maldivian fighter known to have died in Syria was a 44-year-old named as Abu Turab He was later identified as Ali Adam from the island of Feydhoo in Shaviyani Atoll5.

Two days later, another man, Abu Nuh, was reported killed in Syria. He was later identified as Hassan Shifaz from the capital island of Male’. Since then, around a dozen Maldivians are known to have died fighting in Syria.

Figure 2 Abu Nuh, second Maldivian to die in Syria

Authorities differ greatly on the number of Maldivians who have travelled to join the war in Syria. The most recent police estimate put the figure at 50, while the Maldivian Democratic Party (MDP) puts the figure at around 200. While it is hard to get an accurate figure, judging from the number of reported deaths and the increasing numbers reported as leaving for Syria, the police estimate is ultra-conservative and, not unintentionally, misleading. The Maldives Police Service and the government have been largely6 unable or unwilling to address the issue. This is not surprising, given the links said to exist between the government, Islamists and law enforcement authorities7. At the UN Human Rights Council’s Universal Periodic Review in Geneva on 6 May 2015, Maldivian Foreign Minister Dunya Maumoon denied any Maldivian links to terrorism, and refrained from making any reference to the growing number of people leaving to Syria.

In contrast to the government’s reluctant admission to existence of limited extremism, the opposition has, for several years now, highlighted religious extremism as a major concern. Their figure of 200 fighters in Syria, however, appears inflated—at least for now. A more accurate figure would be somewhere in-between. From a population of just over 300,000 this is still a shockingly large number. There are more Maldivian fighters in Syria than there are from Afghanistan or many other countries in the Middle East8.

‘Hijra’ in large groups

In October 2014, Ahsan Ibrahim (23) left for Syria with his mother, wife and 11-year-old sister. They left their island Meedhoo, in Raa Atoll, on the pretext of seeking medical treatment in the capital Male’. Ali Ibrahim, father of Ahsan and the 11-year-old girl, only became aware of their plans a week later. In the five months since, Ali Ibrahim has only heard from his family once. ‘We are in Iraq’, Ahsan told his father in a phone call made on Viber. Ahsan told his father they have no intention of returning to the Maldives, which he described as ‘a land of sin’. They left it behind to be ‘on the right path’. With help from Maldivian authorities Ali Ibrahim confirmed his family has crossed the Turkish border into Syria, but he has no way of knowing whether his wife and children are dead or alive.9

Increasingly, Maldivians are leaving for Syria in large groups. This new trend can be spotted from early January 2015 onwards, when it was reported that a group of seven Maldivians had left together for Syria. It was also the first time connections emerged between dangerous criminal elements in society and those travelling to Syria. All seven members of the group belonged to a criminal gang. Among them was Azleef Rauf, a notorious gangster accused of involvement, among other violent crimes, in the murder of Dr Afrasheem Ali, an MP and a religious scholar known for relatively moderate views. The group entered Syria via the Turkish border. According to local media reports, Azleef planned to take his pregnant wife, one-year-old son and four-year-old daughter with him but was prevented by the wife’s family.10

Another group of six, en route to Syria to join with Azleef’s group, were stopped in Malaysia and returned to the Maldives on 12 January 2015. Their plans were reported to the police by a family member and four were stopped by a joint operation by Malaysian and Maldives police. Whereabouts of the other two are unknown, but they are believed to be in Indonesia11.

Another group of six Maldivians left for Syria on 29 January 2015. The group included the Imam of a mosque in capital Male’,

Check out my new article co-authored with Oula Abdulhamid Alrifai for The National Interest: "Assad Plays America the Fool… Again"

Last decade, Bashar al-Assad’s regime fooled Washington into believing that he would bring about reform. He did not. The lack of institutional and economic reforms led to the uprising and civil war in Syria.

It is a shame then that Assad is fooling Washington a second time, now arguing he is the lesser of two evils compared to ISIS, an argument that has influenced Secretary of State John Kerry, who is now calling for negotiations. Assad’s regime is just as bad as ISIS. If Washington falls for Assad’s manipulation and deceptions again, what will be the result?

The stakes are greater now than in the last decade and the security situation more tenuous, so why would anyone put trust in a regime that has not only failed its own people, but also blatantly conned Western leaders not once, but twice?

Assad’s “reforms” were nothing more than a thin cover for further corruption. There was never a real intention to improve economic or living conditions. Not only was the international community fooled, but many Syrians bought into the lies. It did not take long for the “ophthalmologist” to be proven short-sighted as protesters took to the streets in Damascus in February 2011 chanting “Syrian people will not be humiliated!” Forty percent of Syria’s population was living under the poverty line and more than twenty-five percent of young men were unemployed. Consequently, many Syrians were immigrating to neighboring countries looking for work and a better life.

According to United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), between 2003-2004, two million Syrians could not obtain basic needs. Fifty-six percent of Syria’s rural population depend on agriculture for survival, and in 2004,more than seventy-seven percent of them were landless. Today, the situation is substantially worse despite Assad’s June 2014 referendum campaign dubbed“Sawa” to “improve” Syria’s economy. In fact, the overall poverty rate has nowreached eighty percent.

Shopping malls and high-rise hotels were purposely built in Damascus to fool tourists, journalists, celebrities, and goodwill ambassadors. Even elites and upper-class families found shopping at these malls too expensive. The middle-class was crushed during Assad’s “reform era” and the gap between rich and poor was growing ever wider. In contrast, the families of the regime and its allies were making billions. The era of pseudo-reforms led to a mass exodus of the population to the cities, which only became more acute during a droughtlast decade.

With the rise of ISIS and its open brutality, the United States has stoppedcalling for the overthrow of Assad and is actually now working together with Assad to “defeat” ISIS. This is the height of delusion. From the beginning of the uprising, the regime portrayed non-violent protesters as terrorists even though they were not. Assad needed to create the atmosphere, which would lead to the rise of more radicals in order to serve his narrative and “prove” that the choice boiled down to either him or the “terrorists.” Assad has been the godfather of ISIS and other jihadis. The regime guessed correctly that Washington would fall for this.

The regime is one of the key reasons why radicals were able to flourish post-uprising. It is true that elements within the mainstream rebellion did not push back against the rise of radicals, in part due to short-sighted leadership and Islamist co-optation, but Assad was the one that put many of the radicals back out onto the battlefield after he released numerous radicalized individuals from Sednaya prison in mid-2011.

Ninety percent of those in the prison had been accused of previously fighting in Iraq and key Jabhat al-Nusra, Ahrar al-Sham, and Jaysh al-Islam leaders were part of this “amnesty.” Their subsequent actions were the logical conclusion of a radicalization process that occurred over the previous decade due to the regime’s treatment of prisoners. Besides heavily-documentedphysical torture, the regime mentally and emotionally abused prisoners through burning, urinating, and stepping on the Qur’an. Additionally, the prison was located in a Christian town known for large-scale religious ceremonies and partying. These carefully orchestrated actions created the setting for the incubation of radicalization.

This type of manipulation is nothing new, and the regime helped facilitate and train members of al-Qaeda in Iraq last decade as well as enabled Fatah al-Islam in Lebanon. Once these radicals were freed in 2011, Assad’s military focused on mainly fighting the mainstream rebels while only occasionally targeting the radicals. This is because the regime knew that jihadis would also move against the rebels, indirectly helping the regime. Both were mutually benefiting from one another even if there was no coordination. Because of this, the Assad regime can now claim that he is fighting terrorists as the pool of moderates has shrunk due to the regime and jihadi onslaught.

This policy got more out of control than the regime would have predicted: the consolidation of three provinces (Jabhat al-Nusra in Idlib and ISIS in al-Raqqa and Deir al-Zour) under jihadi control. Even with the assistance of the Iranian Revolutionary Guards, Hezbollah, and others, Assad cannot roll back these groups due to a lack of capacity, illustrating the inability of the regime to have true sovereignty over Syria. And this is without even mentioning that mainstream rebels also control parts of the north and south, Israel’s airstrikes against Hezbollah, coalition airstrikes against Jabhat al-Nusra and ISIS, and Turkey sending tanks into Syria to protect the tomb of Süleyman Şah.

Closer to the regime, the power of the jihadis has grown, demonstrating it is not just a periphery issue. ISIS gained the allegiance of the Rijal al-Haq rebels in Wadi Barada area in Rif Dimashq (Damascus countryside). It has also taken control of Hajr al-Aswad, fifteen minutes from the center of Damascus–about the distance from Silver Spring to downtown Washington, D.C. Additionally, Jabhat al-Nusra conducted a suicide bombing of a bus of alleged Shia pilgrims outside the Citadel of Damascus. Another group, Jaysh al-Islam shelled the core of Damascus. If the regime cannot keep the peace where it is based, how can one expect it to do so in the rest of the country?

Even with help of outside forces, Assad has still been losing territory. His regime is more reliant than ever on Iran and Hezbollah. The Revolutionary Consultative Council released a statement saying that Iran is occupying Syria. This shows that Iran is able to gain hegemony over yet another Arab state and put itself in a better position to challenge its rivals in the Gulf. Iran is already consolidating its grip over Iraq, building up proxies in Bahrain, and obtaining closer relations with the Huthis in Yemen. Iran is de-facto surrounding its nemesis Saudi Arabia, which would potentially lead to more brazen policies on its part that would go against American interests and embolden more radicals.

Iran and its Shia-proxy networks in Syria have caused not only the radicalization of the local population, but is the original reason why so many Sunni foreign fighters began to come to Syria. This pushed many moderates into

The Clear Banner: Canadian Foreign Fighters in Syria: An Overview

The Clear Banner sub-blog on Jihadology.net is primarily focused on Sunni foreign fighting. It does not have to just be related to the phenomenon in Syria. It can also cover any location that contains Sunni foreign fighters. If you are interested in writing on this subject please email me at azelin [at] jihadology [dot] net.

—

Canadian Foreign Fighters in Syria: An Overview

By Amarnath Amarasingam

Public Safety Canada noted, in its 2014 terrorist threat assessment as well as later public statements, that the Canadian government was aware of at least 130-145 individuals “with Canadian connections who were abroad and who were suspected of terrorism-related activities” [1]. The Syrian conflict, as well as the more recent establishment of the “caliphate” by the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), has captured the imagination of some Muslim youth from around the world, who now migrate into Syria and Iraq to wage jihad. According to the 2014 threat report, there are at least 30-40 Canadians who are currently fighting in Syria/Iraq [2], but based on interviews with community members in Canada, I would place the number closer to sixty.

While the number of Canadians traveling to Syria has been relatively low, compared to other Western countries like the United Kingdom or Belgium, Canadian fighters have been quite prominently featured by the English-language Al Hayat Media Centre of the Islamic State. Andre Poulin, from Timmins, Ontario, was the first Canadian to appear in Islamic State propaganda materials [3]. The slickly produced video, using stock footage of ski slopes and skyscrapers, runs for eleven minutes and shows Poulin (known as ‘Abu Muslim’) speaking directly to the camera. “Before Islam I was like any other regular Canadian,” he says. “I watched hockey. I went to the cottage in the summertime. I loved to fish.” As the video depicts, Poulin died in August 2013 during an attack on Mennegh Military Airport in Aleppo.

Another Canadian featured in early 2014 is Farah Shirdon from Calgary, Alberta. Shirdon, known as Abu Usamah, can be seen burning his Canadian passport and threatening Western powers [4]. Shirdon, who for a time was thought to have been killed, achieved greater fame when he conducted a Skype interview with Vice News in September 2014 [5]. The most recent Canadian to appear in an Islamic State recruitment video is John Maguire from Ottawa. Standing amidst rubble, Maguire, much like Poulin, implores Muslims in the West to make hijrah, or emigrate, to the Islamic State [6]. In the interim period between the Poulin and Maguire videos, the Canadian government joined the coalition of countries seeking to militarily dismantle the Islamic State. Accordingly, Maguire’s video is more confrontational, lambasting the Canadian government for its military aggression, and arguing that the attacks in Ottawa and Montreal in October 2014 should be seen as a natural consequence.

The Canadian Clusters

Since early 2014, I have been tracking and attempting to build a database of Canadian fighters in Syria and Iraq. In discussions with community members, friends and families, and journalists, we have confirmed the identities (albeit unevenly and incompletely) of around 35-40 Canadians who have traveled to Syria and Iraq. Of these Canadians, at least 5-7 individuals are women and 5-7 are converts to Islam. At the time of writing, at least 12 Canadians have died in the fighting – 7 from Alberta, 4 from Ontario, and 1 from Quebec. The vast majority of fighters are first or second generation youth who were born Muslim into a variety of South Asian and Middle Eastern backgrounds. As many scholars have noted, there is no one single profile of these individuals – their ethnic, cultural, economic and religious backgrounds are varied and diverse. What does seem to be a common characteristic of almost all Canadian foreign fighters is the role played by group dynamics and friendship networks in influencing their decision to fight abroad [7].

One of the first clusters that the Canadian public became aware of was in Calgary, Alberta. The Calgary cluster consisted of Damian Clairmont, Salman Ashrafi, Gregory and Collin Gordon, Farah Shirdon, as well as a few other individuals who have yet to be identified [8]. While they were friends, their biographical details are quite varied. Ashrafi was born Muslim, educated at the University of Lethbridge, held a prestigious job at Talisman Energy, and was married with a child at the time of his departure in November or December 2012. In November 2013, he engaged in a suicide attack in Iraq that would kill him and 40 others [9].

Clairmont, on the other hand, was a white convert, suffered from bipolar disorder, was a high school dropout, and was homeless for a time in Calgary. Clairmont and Ashrafi were close friends and part of a study circle with the Gordon brothers and several others. In interviews with their friends in Calgary, it is evident that Clairmont was the dominant personality, and influenced many of the other young men. Clairmont would leave Calgary in late 2012. He fought with the Al-Qaeda affiliated Jabhat Al-Nusra, and was captured and killed by the Free Syrian Army in January 2014 [10].

Another fighter with some connection to the Calgary study circle is Ahmed Waseem from Windsor, Ontario. Waseem’s story is particularly interesting because he came back to Canada after an injury sometime in 2013 [11]. After experiencing increased surveillance and having his passport seized by Canadian intelligence agents, he secured a fraudulent passport and has, according to his Twitter feed (now suspended), been regularly involved in fierce battles in Syria ever since.

While it was the Calgary cluster that initially made the news in Canada, Ontario is still home to a far greater number of foreign fighters than Alberta. Of the Canadian foreign fighters in Syria and Iraq, close to half are from Ontario. Perhaps the most intriguing case is the story of Andre Poulin from Timmins. Born in 1989, Poulin converted from Roman Catholicism sometime in 2009, noting in an online forum that he was “convinced through the scientific nature of the Qur’an that it was indeed the truth.” Poulin traveled to Syria in November or December 2012.

In the early stages of researching Poulin’s story, he did not seem to be part of any “cluster” – indeed, there are only a handful of Muslims in Timmins, a small city of 43,000 people with no mosque. Around 2011, Poulin told family and friends that he was moving to Toronto to be closer to Muslims. In Toronto, Poulin met with Muhammad Ali from Mississauga [12]. They had become friends in an online forum long before this first meeting. Once Poulin was in Toronto, they would see each other regularly. Ali was born in 1990 and went to Ryerson University to study aerospace engineering. He did not do well in school, however, and was kicked out a year later. It was then that he started asking questions about life and the afterlife, and found many of the answers in Islam, the religion of his upbringing. He went to online forums and began interacting with fellow Muslims – one of them being Poulin. Ali would leave for Syria in April 2014, several months after Poulin had died.

Poulin made other friends as well, and seems to have influenced them towards his way of thinking. At least four others from Toronto – Tabirul Islam, Abdul Malik, Noor, and Adib – became friends with Poulin and left for Syria around the same time he did. However, very little is known about them currently, except that some or all of them returned to Toronto in Feb 2013 – only to leave again in July 2014. Interestingly, on 13 July 2014, Muhammad Ali posted a screenshot of a text-message conversation he was having on his phone. The message read: “This is the friends of Omar Abu Muslim from Canada. We are in Turkey now and we want to know which way to get into Syria and join Islamic State.” From this message we can deduce that while Ali and Poulin were friends in Toronto, Ali likely did not know Poulin’s other Toronto friends until later. In discussions with some members of the Islamic State over social media, it seems likely that these four Canadians may currently be fighting in Iraq.

Despite these significant gaps we know quite a bit about the Calgary and Toronto clusters. As of this writing, community sources in Edmonton also confirmed that three Somali Canadians – brothers Hamsa and Hirsi Kariye and their cousin Mahad Hersi – had died fighting in Syria, and as many as ten may have departed from the city in 2014. In early March 2015, it was also reported that six individuals from Quebec (the Laval and Montreal areas) – Bilel Zouaidia, Shayma Senouci, Mohamed Rifaat, Imad Eddine Rafai, Ouardia Kadem, and Yahia Alaoui Ismaili – had departed to the Islamic State. There are also discussions in various communities across the country of possible clusters in a variety of major cities across Canada. At the moment, however, very little is known about them.

Conclusion: Foreign Conflicts, Local Implications

The involvement of Canadians in foreign conflicts has always been a cause for concern. There are fears that Canadians may contribute, either financially or otherwise, to violent social movements abroad. There are related fears that these individuals may arrive back in Canada to radicalize others or to launch attacks on the homeland. As the 2014 threat assessment noted, “The Government is aware of about 80 individuals who have returned to Canada after travel abroad for a variety of suspected terrorism-related purposes. Those purposes varied widely.

Some may have engaged in paramilitary activities. Others may have studied in extremist schools, raised money or otherwise supported terrorist groups” [13].

It

The Clear Banner: The Forgotten Fighters: Azerbaijani Foreign Fighters in Syria and Iraq

The Clear Banner sub-blog on Jihadology.net is primarily focused on Sunni foreign fighting. It does not have to just be related to the phenomenon in Syria. It can also cover any location that contains Sunni foreign fighters. If you are interested in writing on this subject please email me at azelin [at] jihadology [dot] net.

—

The Forgotten Fighters: Azerbaijani Foreign Fighters in Syria and Iraq

By North Caucasus Caucus

This article, the first of two parts, will focus on the activities of Azerbaijani foreign fighters in Syria and Iraq in 2014 – their leadership, units, and overall trends. The follow-up will focus on the impact of the conflict in Syria on the Azerbaijani domestic scene and the Azerbaijani government’s response.

My first article on Azerbaijani foreign fighters for Jihadology was published in January 2014 and focused on their activities since the beginning of the conflict in Syria. Several incidents that occurred around that time caused the Azerbaijani mainstream media to begin actively covering developments relating to the actions of their countrymen in Syria. The most prominent such incident occurred on 03 January 2014, when the Islamic Front attack on the Sheikh Suleyman Islamic State (IS) training camp led to the death of six Azerbaijani foreign fighters. During the infighting, some Azerbaijani fighters were reportedly taken hostage, but they were still texting friends in Azerbaijan who posted their messages on Facebook. At this time, Azerbaijani journalists began to follow the social media postings of fighters in Syria regularly.

Since then, the main source of information about the activities and views of fighters has shifted from their own social media postings to mainstream media coverage. With this shift, a problem has arisen of parsing fact from misinterpretation, as well as the general lack of fact-checking endemic to the Azerbaijani media. I have tried to corroborate press reports with social media reporting whenever possible. Repeatedly throughout 2014, the Azerbaijani media published photos of fighters as having recently been killed, when in fact they had been killed up to a year earlier. There were also indications as early as February 2014 that Azerbaijani foreign fighters were aware of the scrutiny of their online activities and were in some cases counting on the media helping to distribute their messages or videos.

One somewhat surprising trend that has held since the publication of my last article is that there have been no confirmed reports of Azerbaijani citizens fighting with pro-government Shi’a units in Syria or Iraq, despite Shi’a making up approximately 70% of Azerbaijan’s population (though the occasional news story on the trend is still occasionally published). Instead, all confirmed Azerbaijani foreign fighters in Syria have fought with Sunni rebel groups, and many with IS in particular. Although an Azerbaijani Sunni news website posted the names of eight Azerbaijanis from Nardaran, the center of conservative Shiism in Azerbaijan, and claimed they had been killed in Syria, leaders from Nardaran denied the story. No visual evidence has emerged to corroborate it and the claims remain questionable considering the source. The impact of Syria on sectarian issues within Azerbaijan will be covered in-depth in a follow-up to this piece.

Hometowns and Numbers

Despite some very prominent databases overlooking Azerbaijani foreign fighters, leading to their exclusion from several prominent infographics, they continue to have a presence in Syria and Iraq. Azerbaijani media outlets consistently report that close to 200 Azerbaijanis have died fighting in Syria since the beginning of the conflict. An April 2014 estimate put the number of Azerbaijanis in Syria at approximately 250. In May 2014, according to a survey of 40 police districts in Azerbaijan, 104 people were identified as having gone to fight in Syria, with 60 killed. In December, the Azerbaijani Border Service reported that 30 returning former fighters had been detained throughout the year.

Along with fellow analysts, I have identified 216 Azerbaijani foreign fighters and their family members in Syria (88 killed, including 64 in 2014 alone, 49 returned, of whom 40 were arrested, 66 still in Syria or Iraq, and 13 whose status is unknown). The number is likely higher since this database only includes fighters and their family members with some unique personal identifying information.

The hometowns of fighters remain relatively consistent with the data from 2013. According to the survey of police districts mentioned above, of the 104 identified by police, 40 were from Sumqayit, 22 from Shabran, and 15 from Qusar. Other locations mentioned in the police report were Xacmaz, Zaqatala, Qax, Yevlax, Oguz, Quba, and Sheki. From my own data, Baku, Terter, and Ismayilli were also other hometowns that appeared to be prominent.

Units

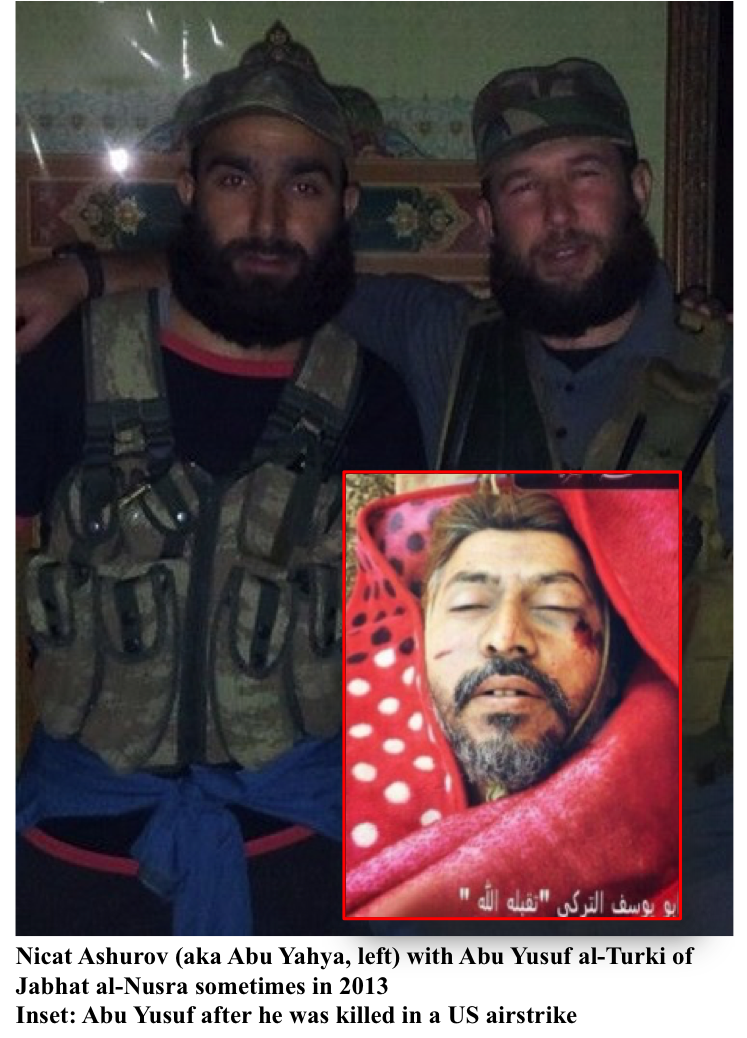

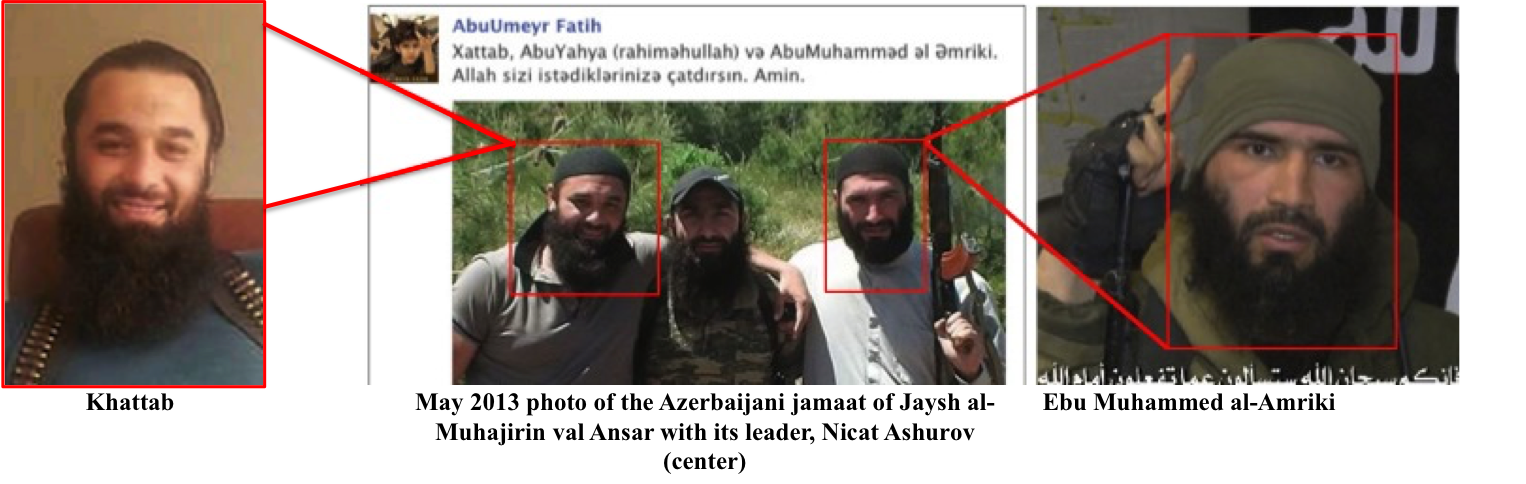

At the beginning of 2013, Azerbaijani foreign fighters started out primarily fighting with the Azerbaijani jamaat of Jaysh al-Muhajirin val Ansar, led by the charismatic leader and face of Azerbaijani fighters in Syria, Nicat Ashurov (aka Abu Yahya al-Azeri). After Ashurov was killed in September 2013, the majority of Azerbaijani fighters appeared to have joined the Islamic State.

Islamic State

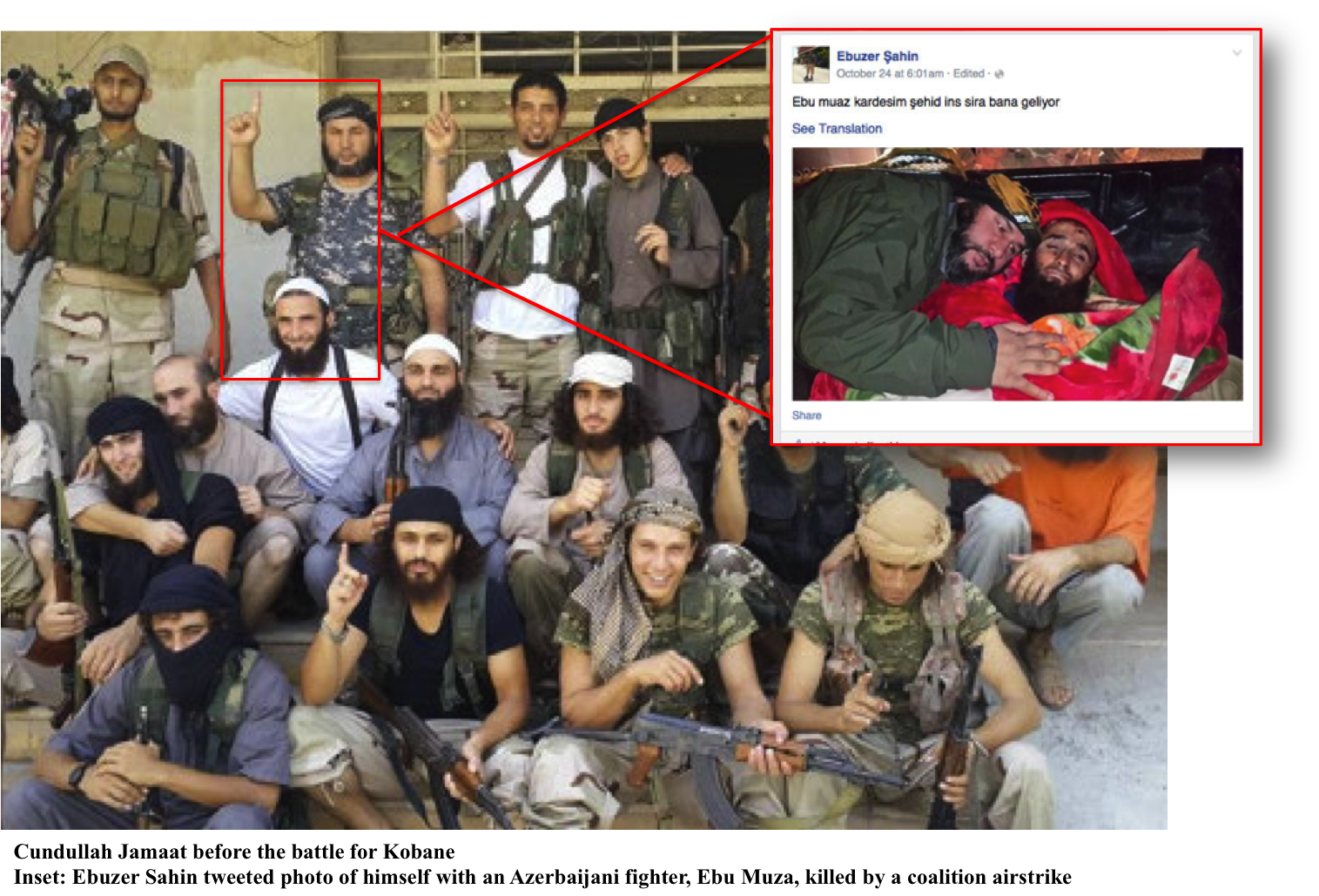

Though an Azerbaijani fighter appeared in photos posted by the Twitter account of the Bitar Battalion, a predominately Libyan affiliate of IS, there appear to be two primary units within IS in which Azerbaijanis fight. The first is a mixed Turkish-Azerbaijani unit previously based on Raqqa, which appears to have been engaged in Kobane. Ebuzer Sahin, a Turkish citizen and likely spiritual leader of the unit identified it on social media as the Cundullah (pronounced Jundullah) jamaat.

Jabhat al-Nusra (JAN)

Despite the majority of Azerbaijani foreign fighters appearing to fight with IS, there are at least several still fighting within various JAN units. In early 2014, Fariz Abdullayev from Sumqayit was reported killed in Syria. As recently as 18 December, Ruslan Aliyev was reported to have been killed fighting in attack on Wadi al-Deif military base in Idlib, likely fighting alongside Jabhat al-Nusra that was engaged there.

Azerbaijanis have also aided in the JAN-IS propaganda war. In May 2014, A pro-JAN Turkish language outlet Ummetislam.com, published an interview conducted by Turkish Islamist journalist Muhammed Isra with a man named Ebu Hasan Kerimov, an alleged IS defector who disparaged the group and its activities. He described how he travelled to Sanliurfa in southern Turkey and met with an IS facilitator who smuggled him into Raqqa via Tal Abyad.

Conversely an Azerbaijani was part of a major propaganda coup by IS against JAN. In February 2014, an English-speaking fighter calling himself Abu Muhammed al-Amriki briefly gained some prominence. In the video Abu Muhammed claimed that he had lived in the US for 10-11 years and described when he had left JAN to join IS. The video gained enough attention that Abu Muhammad al-Jolani, JAN’s emir personally responded to al-Amriki’s accusations. There is strong evidence that Abu Muhammed (who was reportedly killed by an airstrike in October 2014) was an Azerbaijani in reality (though he might have been a resident of the US at some point). First, Abu Muhammed appeared in a major address by Abu Yahya in May 2013. In the address, Abu Yahya calls on his countrymen to come to Syria and join the Azerbaijani jamaat of Jaysh al-Muhajirin val Ansar, indicating all the men appearing in the video. Besides the February video in which Abu Muhammed spoke English, he appeared in a number of other videos in which he exclusively spoke Russian. Second, Turkish IS member Ebuzer Sahin posted a photo of himself with Abu Muhammed, indicating that he was also from Azerbaijan. He was likely primarily a Russian speaker.

Leadership

The death of Ashurov (mentioned above) in September 2013 appears to have been a major blow to Azerbaijani fighters in Syria. Ashurov appears to have been communicating with contacts in Azerbaijan and trying to convince them to join the fight. Since Ashurov’s death, several other leaders have emerged, but none appear to command the same respect.

“Karabakh Partisans”

Some of the leadership came from an older cadre of Azerbaijani jihadis – including those who fought in Afghanistan and Chechnya. Several of the experienced Azerbaijani jihadis in Syria had been part of a group known as a “Karabakh Partisans.” This was a group of Azerbaijanis who fought in Chechnya and then desired to start a jihadi paramilitary campaign against Armenian forces in Nagorno-Karabakh. Azerbaijani security forces captured and imprisoned them in 2004. However, a number of those imprisoned were quietly released in 2010. One of these fighters was a highly respected fighter, Rustem Askerov, who was killed in 2013. More information about this fighter emerged in 2014. A journalist from al Jazeera Turkish interviewed Askerov’s mother, who still lives in Baku and is taking care of three of his children. Askerov had attended religious studies in Medina in 1998 before eventually going to fight in Chechnya.

Rovshan Badalov, a second member of the “Karabakh Partisans” was killed in Kobane in October 2014 – some reports claim he was killed in an airstrike, while others state he conducted a suicide attack. Like Rustem Askerov, Badalov had also fought in Chechnya in 2001, reportedly leading a group called the Tabuk jamaat. According to a report from Azerinfo, Badalov had connections to the pro-IS Turkish preacher

The Clear Banner: Tajik Fighters in Iraq and Syria

The Clear Banner sub-blog on Jihadology.net is primarily focused on Sunni foreign fighting. It does not have to just be related to the phenomenon in Syria. It can also cover any location that contains Sunni foreign fighters. If you are interested in writing on this subject please email me at azelin [at] jihadology [dot] net.

–

Tajik Fighters in Iraq and Syria

By Edward Lemon

Wreaked by violence in the 1990s, Tajikistan played host to prominent Arab foreign fighters including Ibn Khattab and Abu Walid. Now the situation has reversed and young men are travelling from the mountainous Central Asian republic to fight in Iraq and Syria. Whereas some of the first reported fighters joined Jabhat al-Nusra, now the vast majority have been lured into the ranks of the Islamic State.

With a population of almost eight million, the post-Soviet republic of Tajikistan lies in Central Asia. Ruled by strongman president Emomali Rahmon since 1992, the government defeated an opposition it labelled as “Islamist” in the country’s civil war. Remittances sent by more than a million migrants in Russia form the backbone of the economy, with narcotics smuggling from Afghanistan also playing a key role. Although the majority of the population are Muslim, a seventy year Soviet-led campaign against religion has rendered understandings of Islam as secular; Islam is a key part of national identity but does not correspond to a defined set of beliefs and practices.

Continuing in the footsteps of its predecessor, the Tajik government has promoted a good, national religion, and restricted bad, foreign forms of Islam. Salafism was banned in 2009, studying in foreign madrassas without a permit was criminalised in 2011, and imams were given a list of approved sermon topics in 2012. Tajiks who have joined the Islamic State are reacting to this assertive state secularism back home.

Unsubstantiated Estimates: How many Tajiks are Fighting with the Islamic State?

A great deal of scaremongering surrounds the foreign fighter problem in Central Asia. Russian experts, eyeing a return to the Afghan-Tajik border, which it left in 2005, have been keen to highlight the imminent threat that the Islamic State poses to the region. Yevgeny Satanovsky, president of the Russian Institute for Middle East Studies, stated in September that “the catastrophic wave of violence at the hands of the Islamic State will repeat itself in Afghanistan and then move on to Central Asia.” According to Satanovsky, as many as five thousand Central Asian nationals have uprooted for Syria and Iraq. In late October, Rafal Rohozynsky – identified as a Canadian terrorism expert – told a conference in Astana that four thousand Central Asians are fighting with the Islamic State. He claimed he derived the figure from a “careful” reading of online material. His comments were widely circulated by Russian language news services.

International news agencies have been even more arbitrary in guessing the number of Tajik foreign fighters in Syria and Iraq. In September, a CNN map did not mention Central Asian fighters at all. The next month, the Washington Post published a map stating that thirty Kyrgyz fighters were in Syria; it ignored all the other Central Asian republics.

Ever eager to appear in control, the Tajik government itself has offered more circumspect figures. Addressing officials in September 2014, President Emomali Rahmon said that two hundred Tajik nationals are fighting in Syria. This figure conflicts with the State Committee on National Security’s estimate of three hundred. Interior Minister Ramazon Rahimzoda announced in October that fifty Tajiks have been killed in Syria, though only eleven of these deaths have been reported. Online evidence for sixty five fighters exists. This figure includes twenty fighters from the village of Chorqishloq in the north of Tajikistan. Of these, eleven have been reported killed and a further twenty arrested. The fate of the remaining thirty two remains unreported.

Profiling Tajik Fighters in Syria and Iraq

All the reported Tajik fighters have been young men; the oldest being 41 and the youngest 23. Most fighters are recruited in Russia. From Russia, like most foreign fighters, Tajik jihadists transit through Turkey to reach Syria. Approximately one million Tajiks currently work in Russia. Migrants are allegedly more “vulnerable” to radicalisation. They work in low-paid jobs, often experience xenophobia, and endure abuse at the hands of the government. The offer of a steady income and potential glory of becoming shadid (a martyr) in Syria may be a tempting prospect for some disillusioned young migrants. Although a link between migration and radicalisation seems to exist, this remains an understudied phenomenon. Further study is needed in order to examine the dynamics through which this relationship manifests itself.

Many of the fighters did not express an interest in religion before they left Tajikistan. After a video of Islamic State fighter Akhtam Olimov appeared online in September 2014, his family were in shock. Neighbours commented that he was never particularly pious when growing up. “He never wore a beard” before he went to Russia, his mother told reporters. After Bobojon Kurbonov was killed in August 2014, his brother told the media that “Bobodjon was not a religious man, and we do not understand how he was persuaded to go to war.” Like many young Muslims who join extremist groups, the Tajik recruits appear to lack knowledge of the Qu’ran, Sunnah, Sharia, or hadith.

The case of twenty six year old Bakhtiyor Sherov – also known as Abu Akhmad Tajiki – is typical. Born in Kulob in the south of Tajikistan, like many of his countrymen he left for Russia in 2011. After sending money back to his family for a few months, he disappeared. The next thing his family knew he was dead. Sherov was killed fighting with al-Nusra in March 2014.

The Role of Tajik Jihadists in Syria and Iraq

Recently, users uploaded twenty videos showing Tajiks fighting with the Islamic State to Russian social networking site Odnoklassniki (Classmates). Ranging from scenes of jihadists eating dinner, joking in a public square, and warnings to the Tajik government, the videos shed some light on the lives of foreign fighters in al-Sham. In one video, a man who identifies himself as Abu Umariyon can be seen at the checkpoint on the edge of an Iraqi town. He stops a car and, speaking in broken Arabic, checks that the driver is not carrying contraband cigarettes.

It is clear that the Tajiks have connections with fellow Russian speaking jihadists from the North Caucasus, Russia, and the other Central Asian republics. In September 2014, Iraqi TV showed an interview with twenty five year old Tajik national Olim Yusuf who had been arrested on the border with Syria. Although he admitted to working for the Islamic State, he said he was only a driver. His interrogation, however, suggested links with fellow Russian speaking fighters. According to Yusuf, “I went to Raqqa, to a town called Sadaashri. We spent 14 days there. The camp was commanded by Umar Shishani [IS Chechen leader]. There were 18 or 20 people there. Some were Arabs and others were Chechens.” In the interview Yusuf claims that he did not participate in the hostilities.

The Government’s Repressive Response

The Tajik government has frequently highlighted the potential threat posed by violent radicalisation. President Rahmon has referred to IS as “the plague of the new century and a global threat” and warned Tajiks not to underestimate the “negative role in Tajikistan” of the militant group. Evidence of the threat posed by returnees has been deployed by the regime. In October 2014 the government foiled a terrorist plot to blow up two major tunnels in the north of the country; the group, it claimed, had links with Syria. In response to the foreign fighter problem, Tajik legislators amended to Criminal Code in May 2014 so that it now covers fighting abroad; those found guilty will be jailed for twenty years. The country’s clerical council has also issued a fatwa against travelling abroad to fight, calling it a “great sin.”

Although the government has frequently announced that it will amnesty any fighters who return and even paraded one reformed “returnee” on national TV, the evidence on the ground indicates a less tolerant policy. The spectre of the Islamic State has been used to legitimise a crackdown on “foreign” forms of Islam. The first Tajik citizens with links to Syria were imprisoned in December 2013. By the end of 2014, one hundred and sixteen citizens had been arrested on charges of “extremism,” almost twice as many as in previous years. A witch hunt is well and truly under way. The walls of local police

The Clear Banner: French Foreign Fighters in Iraq 2003-2008

The Clear Banner sub-blog on Jihadology.net is primarily focused on Sunni foreign fighting. It does not have to just be related to the phenomenon in Syria. It can also cover any location that contains Sunni foreign fighters. If you are interested in writing on this subject please email me at azelin [at] jihadology [dot] net.

—

French Foreign Fighters in Iraq 2003 – 2008

By Timothy Holman

Initial assessments by French and US intelligence from 2005, cited in press in 2008, evaluated that there was a significant risk of attacks by eventual returnees from the Iraq theatre. These assessments were drawn-up amongst early reports of hundreds of foreign fighters from Europe.i By 2008, the numbers of European foreign fighters had not reached the initially anticipated volumes and attacks had not materialized.ii In fact, French foreign fighters were now seeking to enter Afghanistan, having abandoned the idea of foreign fighting in Iraq as either too dangerous or as no longer being a ‘pristine jihad’.iii

The attention of French and other Western authorities turned to al-Qaeda core (AQC) members in the Af/Pak zone who remained active in planning and supporting attacks against the West, and later towards Yemen, where a rejuvenated al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), demonstrated deadly intent and resourcefulness in targeting the United States.iv The Iraq-era networks and their apparently diminishing threat slowly receded into the background as these AQ-affiliated entities focused their attention on attacking the West. The beginning of the conflict in Syria and the flood of European foreign fighters meant the Iraq-era networks were for the most part not a subject of study or analysis.v

The Paris and Toulouse attacks in France were perpetrated by foreign fighters with associations to jihadist networks that first came to the attention of the French authorities in the wake of the United States invasion of Iraq and a renewed surge in interest in foreign fighting. The French and Belgian authorities disrupted these networks in early 2005 (Buttes-Chaumont, Paris) and early 2007 (Artigat, Toulouse region and Brussels, Belgium). Despite the action and activities (arrests, trials and imprisonment) by the French authorities, members of the networks continued to associate, radicalize, and form new relationships, in the context of these evolving networks. In the cases of some, their intent moved from foreign fighting abroad, to attacking inside France.

The French Iraq-era Networks and Clusters

In September 2004, the French authorities opened a judicial investigation into what they termed the ‘filières irakiennes’ (Iraq networks). Six cases were brought to trial; the 19th network/ Buttes-Chaumont group, the Montpellier cluster, the Nice cluster, the Ansar al-Fath group, the Tours cluster, and the Artigat network.vi The 19th network sent the most individuals into Iraq. The Montpellier cluster sent two persons to Syria; one travelled to Iraq, the second desisted and returned to France where he was arrested. The Nice cluster network was an investigation into connections to individuals in the Kari network in Belgium, which also resulted in a trial and convictions. The Ansar al-Fath group was formed around a former Groupe Islamique Armé (GIA) member and individuals he had met in prison. The group initially had the intention of engaging in foreign fighter activity but was redirected into domestic plotting through the instructions of a Syria-based Tunisian facilitator. The group then concentrated its energy into this activity; overseas travel was to Lebanon for training in explosives. The French authorities disrupted the group and the individuals imprisoned.vii In October 2006, three residents of Tours, France traveled to Damascus, Syria with the intention of crossing into Iraq to fight against United States (US) military forces. The three men were rapidly arrested by Syrian security forces as they sought to locate a smuggler to take them across border. They were eventually deported to France and tried.viii This cluster mostly closely resembles the types of individuals that would later participate in the Syria mobilization from France.ix

The Artigat network was a Toulouse-based entity, whose members congregated around a Syrian Afghanistan-veteran in the small town of Artigat. Others traveled to Cairo, Damascus, and in the case of one to Medina, in Saudi Arabia. The travel was for a combination of Arab-language training and to be able to live in countries perceived as better adapted to their faith.x Over-time some members became interested in foreign fighting. Attempts were made to enter Iraq using a Saudi Arabia-based facilitator, who had come into contact with the student based in Medina. The existence and activities of the group became well known to the general public following the 2012 attacks in southwest France by Mohamed Merah. Merah was friends with a core member of the group, and Merah’s brother and sister were also actively engaged in the network. The network continued to exist in some form even after the Toulouse attacks, and members associated with the network have traveled to Syria, including Merah’s sister.xi Since the network formed, participants have been involved in a combination of ‘hijra’, foreign fighting, and domestic terrorist activity.

The story of the 19th network is now well known following the Paris attacks.xii It has origins in Farid Benyettou’s contacts with individuals engaged in militant activity and el-Hakim’s travel to Syria and Iraq and relationships formed while living there. A group of comprised of friends and family members grew around Benyettou in their neighborhood in Paris. Incensed by the war in Iraq and images of Abu Ghraib, the network mobilized to send themselves to fight in Iraq. The group was eventually disrupted from 2004 onwards by a combination of arrests by the US, Syrians and French. A 2008 trial saw members sentenced with some released due to time-served while others returned to prison to see out the remainder of their sentences. In 2010, a small cluster of members through contacts made in prison sought to organize to free an imprisoned GIA bomb maker responsible for the 1995 metro bombings.xiii The planning was organized by a former Afghanistan networks facilitator, Djamel Behgal, who had been assigned to residence following the end of his prison term, while awaiting the result of court proceedings to expel him from France to Algeria. Some members of this group were tried and sentenced in 2013, while others were released due to lack of evidence. A third and final cluster formed between the remnants of the 19th network, and the Beghal cluster. This small cluster would go on to plan and execute the most lethal attacks in France since 1961.xiv

What happened to the French foreign fighters?

Thomas Hegghammer estimates that about 100 European foreign fighters travelled to Iraq.xv My preliminary research has found traces of approximately 54 names of foreign fighters from Europe, who traveled or tried to travel to Iraq from 2003 onwards. They originate from ten countries, nine in Western Europe and one in the Western Balkans. It is probable that there were more fighters, but to-date searches in press reports, judicial documents, martyrs lists, captured terrorist documentation and estimates of captured foreign fighters by the US military give a figure of 54 foreign fighters originating from Europe. This figure is a long way from the estimated 3000 Western Europeans who have traveled to Syria and more recently again to Iraq.xvi

A Preliminary Estimate of European Foreign Fighters in Iraq (2003-2008) and Syria (2011 onwards)

The Iraq numbers are calculated from known travelers to Iraq. The list includes some who were arrested in Syria while attempting to enter Iraq and others who reached Syria but returned home unable to find a facilitator. The Syria numbers come from press reporting or statements by governments compiled in late 2014. See blog post, “Black Math: Getting more from the Foreign Fighter Numbers”, October 10, 2014, https://acrossthegreenmountain.wordpress.com/2014/10/10/black-math-getting-more-from-the-foreign-fighter-numbers/. The French numbers exclude those wanting to travel and those in transit.

Despite the low absolute numbers, but similar to Syria, French foreign fighters formed the largest proportion – 39% – of the European contingent. According to my research there were 21 persons who traveled at least as far as Syria. Marc Trévidic estimates that there were 30 French foreign fighters but publicly available information currently exists for 21.xvii The French foreign fighters came in their majority from the Buttes-Chaumont network. The numbers used in the analysis that follows draw on the figure of 21, as there is some data on what happened to these fighters. The small sample size means that the observations from the analysis are tentative and subject to revision as more information becomes available.xviii

What Happened to the French Foreign Fighters in Iraq

|

Status |

Number |

Notes |

| Arrested in Syria |

5 |

Two from the Artigat network and three from Tours cluster. |

| Dead |

5 |

Four from 19th, and one from Montpellier |

| Imprisoned in Iraq |

1 |

One from 19th (excludes second 19th member who escaped prison and returned to France, counted as a returnee) |

| Returnee |

4 |

Three from 19th and one from Montpellier |

| Unknown |

2 |

Individual who traveled possibly from Marseilles with Italy-based Tunisians, individual mentioned in Sinjar documents. |

| Unknown presumed dead |

3 |

One from 19th, one from Nice cluster and one from Artigat network. |

| Unsuccessful |

1 |

Associate of 19th who traveled later to Syria circa. 2007 |

| Total |

21 |

|

The majority of the French foreign fighters traveled in two waves to try and enter Iraq, 41% (9 fighters) in 2004 and 30% (6 fighters) in 2006. The largest number of successful entries was in 2004, when all of the foreign fighters were able to enter Iraq compared to 2006, when only one of the six travelers is reported to have successfully crossed from Syria into Iraq.

The data indicates that there were four returnees. The Montpellier grouping provided the first returnee, although, this individual’s status as returnee could be questioned, as he appears to have traveled as far as Syria and then renounced traveling further when he understood he could be tasked to carry-out a suicide bombing. The other three returnees came from the 19th network.

Three of the four returnees engaged in some form of domestic activity.

The Clear Banner: Turkish Foreign Fighters and the Ogaden

The Clear Banner sub-blog on Jihadology.net is primarily focused on Sunni foreign fighting. It does not have to just be related to the phenomenon in Syria. It can also cover any location that contains Sunni foreign fighters. If you are interested in writing on this subject please email me at azelin [at] jihadology [dot] net.

—

Turkish Foreign Fighters and the Ogaden

By OSMahmood and North Caucasus Caucus

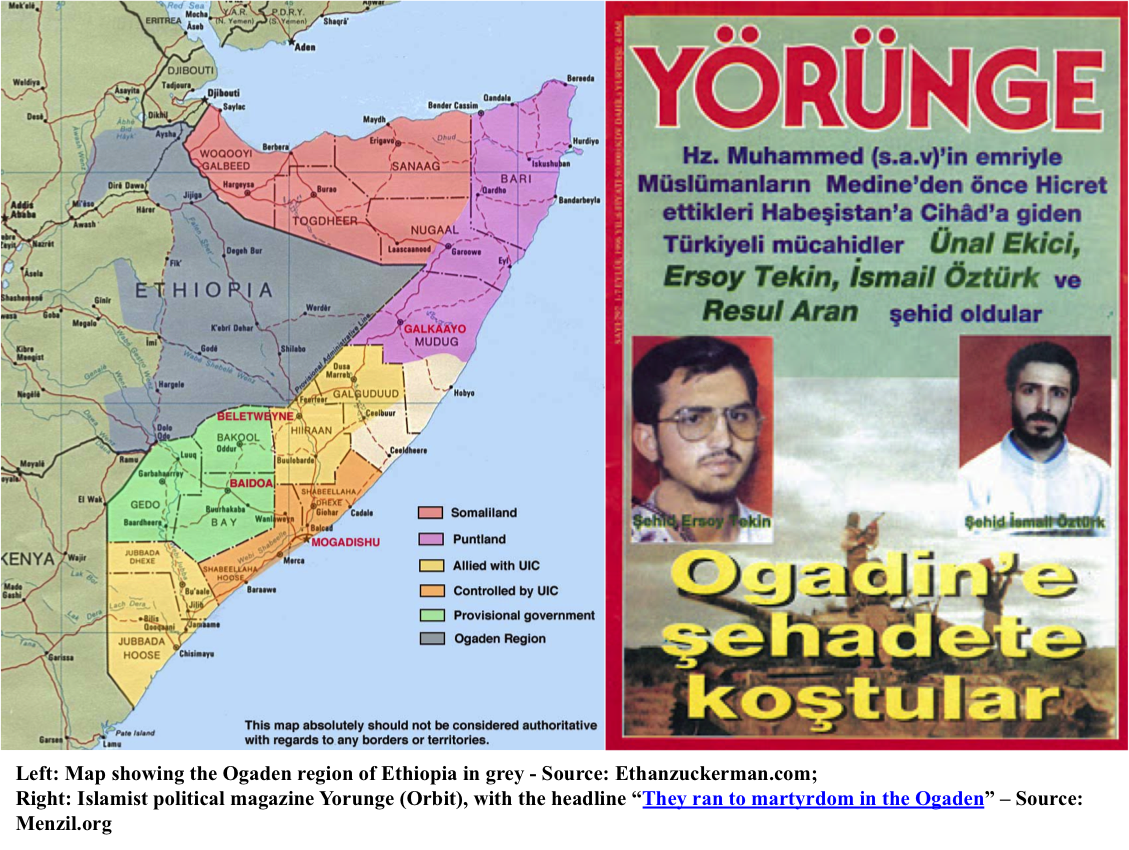

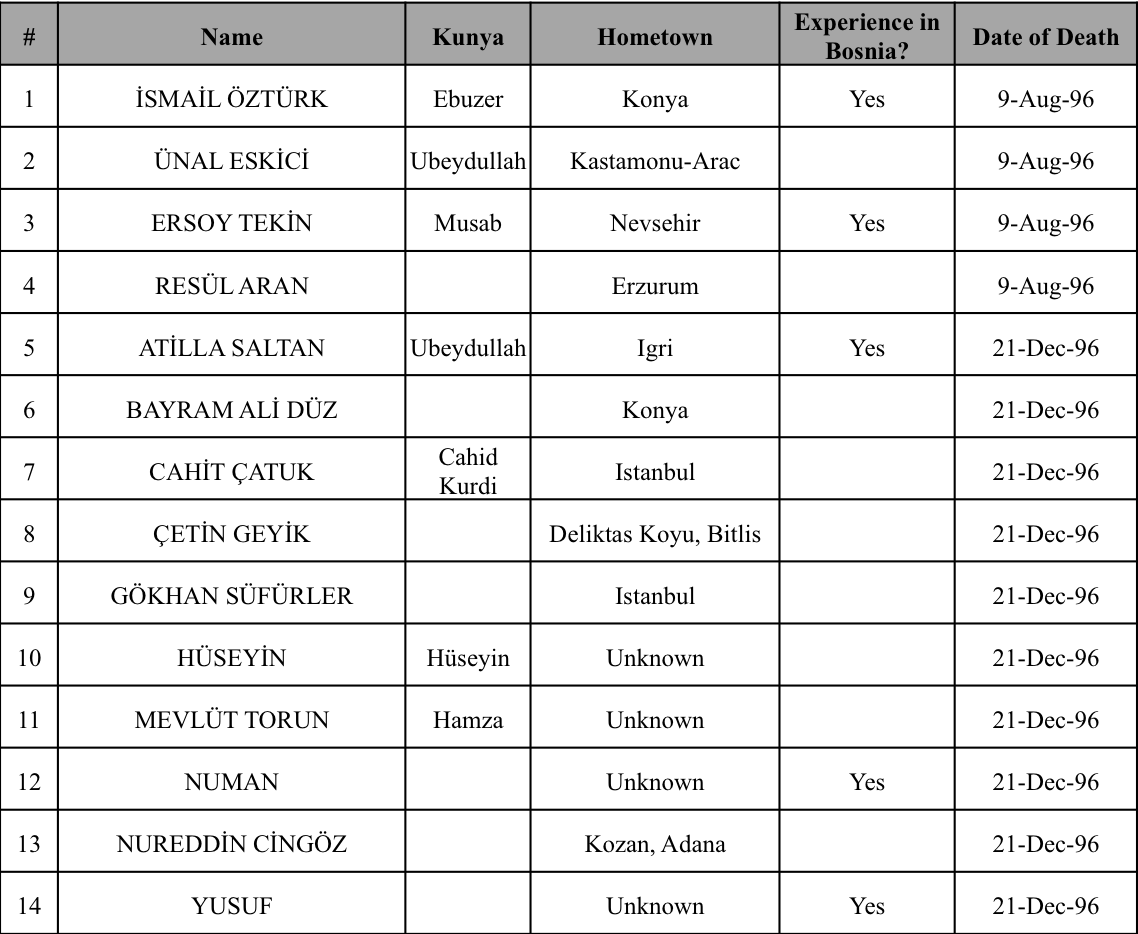

In recent months, there has been a major increase in international media coverage of Turkish citizens fighting alongside The Islamic State (IS). Much of the commentary has focused on the notion that this is abnormal behavior for citizens of the secular state. While this is partially true (the percentage of Turks in IS is even lower than some European countries by comparisons of percentage of total population), it should be recognized that at least for certain communities in Turkey, participating in jihadist conflicts is not abnormal, and those who participate are often honored. To provide a vivid example of this trend, this article will focus on a very specific case from 1996 of 14 Turkish foreign fighters who were killed in one of the lesser-known jihadi conflicts.

Conflict in the Ogaden

The year 1996 must have been a confusing time to be an aspiring jihadi. With the Dayton Accords ending the war in Bosnia the previous year, and the Khasavyurt Agreement temporarily halting hostilities in Chechnya, two of the premiere jihadist conflicts enticing foreign fighters came to an end. Given this context, some jihadis, including a group of young Turkish citizens, looked further afield to participate in one of the more obscure Islamist conflicts – the battle between ethnic Muslim Somalis and Ethiopian government forces in the Ogaden region of Ethiopia.

The Ogaden – A Basic Background

The Ogaden, consisting of the mainly ethnic Somali-inhabited eastern region of Ethiopia, has long had a contentious history. By the early 20th century, the region slowly came under the domain of the Christian empire based in the highlands of central Ethiopia, though control shifted to the British after the Second World War. The British returned the Ogaden to Ethiopia in 1948, along with the Haud in 1954 (the north-eastern section used as a grazing land by nomadic Somali herders), effectively signaling the demise of a ‘Greater Somalia’ that united all Somali-inhabited lands, much to the chagrin of many Somali nationalists.

The reincorporation of the Ogaden into Ethiopia sparked a host of resistance movements and a devastating Cold War-infused proxy battle with Somalia in 1977-78. Following the collapse of the Mengistu government in Ethiopia in 1991, the Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF) assumed control of the region under Ethiopia’s federal structure. The harmonious relationship between the ONLF and the new Ethiopian government, however, did not last – by 1994 the ONLF had divided, with a wing renouncing its political position in favor of armed resistance.

The Rise and Fall of Islamist Interest in the Ogaden

During this time, the struggle for the Ogaden caught the eye of Islamist actors in Somalia. While the ONLF operated as a secular, nationalist party within Ethiopia, often accused of narrowly representing the Ogaden clan, al-Ittihaad al-Islami (AIAI) in Somalia developed a branch focused on the Ogaden that infused Somali irredentism with Islamist rhetoric, adding a new, albeit somewhat peripheral dimension to the struggle. The conflict was often portrayed in terms of Somali Muslims rising up against a Christian entity. Based in Luuq along the Ethiopian-Somali border, AIAI’s Ogaden wing also established training camps within the Ogaden itself, and even conducted a series of attacks in Ethiopia’s two largest cities in 1995-6.

Osama bin Laden also developed an interest in the Ogaden during his stay in Sudan from 1992-96, so much so that during his August 1996 declaration of jihad against the United States, the al Qa’ida (AQ) leader referenced the region amongst a host of other global hotspots where Muslims have suffered at the hands of a “Judeo-Christian alliance.” Representatives from al Qa’ida traveled to the Ogaden in the early 1990s and aided in the establishment of training camps, with bin Laden himself reportedly investing $3 million to bring foreign fighters to the region, cementing the Ogaden on AQ’s early 1990s horizon [Note: The vast majority of open-source information regarding AQ activities in the Ogaden during this time period comes from declassified documents in the Harmony Database, obtained by the Combating Terrorism Center and analyzed in its 2007 report Al-Qaida’s (Mis)Adventures in the Horn of Africa].

Ethiopia, however, responded forcefully to the 1995-6 attacks, bombing camps in Luuq on 9 August 1996 and again in January 1997, effectively routing AIAI. Combined with Osama bin Laden’s move to Afghanistan and AQ’s struggles in Somalia, the Ogaden likely fell off AQ’s map. With AIAI decimated, resistance to Ethiopian rule returned to the realm of the secular, clan-based ONLF, a stiutation that largely persists to the present day.

Turkish Involvement in the Ogaden

Much of the information for this article was drawn from Turkish language sites dedicated to Turkish Islamist martyrs killed in conflicts outside Turkey (as well as those killed fighting Kurdish separatists), such as sehidlerimiz.com and menzil.org. These websites purport to reproduce contemporary reporting from the time of the fighters’ deaths and often provide images of the news articles, primarily from local newspapers. Due to the age and second hand nature of much of this material, some caveats apply, especially as data on Turkish fighters who may have gone to fight but ultimately survived is not available.

As in Syria, looking into the backgrounds of fighters reveals connections to other jihadist conflicts and/or friends and family serving as pulling factors. Below we will describe the experience of a number of the Turkish fighters – who likely joined with the Islamist AIAI’s Ogaden wing, and were all reportedly killed along the Ethiopian-Somali border on two different days between August and December 1996.

Backgrounds and Parental Involvement

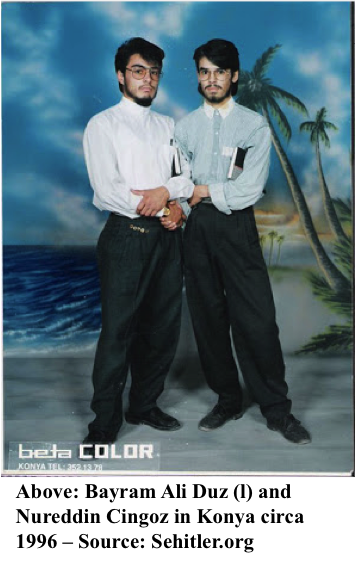

From the available information, the majority of the 14 Turkish fighters killed in Ogaden had similar backgrounds – early 20s, often college students or professionals, and idealistic. One fighter, Nureddin Cingöz from Kozan, Adana, had graduated from a theological imam-hatip high school, where he allegedly won first place in a hadith knowledge competition. However, when he left with his friend, Bayram Ali Düz, for the Ogaden, both were students at Konya’s Selcuk University.

In some cases, fighters seemed to travel without support from their families. For example, Gökhan Süfürler graduated from a vocational high school in Istanbul before taking a job as an accountant working at a company in Kartal. After he left his job, Süfürler’s father wanted him to work at a different job before completing his military service, but Süfürler “claimed to have higher ideals,” according to his father. According to a letter he sent home, Süfürler wrote that he felt guilty living a good life in Turkey while injustice and deprivation occurred elsewhere. In an interview with Selam Gazetesi, Sufurler’s father explained that while he was born in Istanbul, his family was originally from Salonica, Greece and was quite secular. However, his father and other family members started praying more regularly after his son’s death.

In other cases, families appear to have been supportive. In an interview after his death in the Ogaden, Ismail Ozturk’s father stated that his son’s death should not be treated as a tragedy, but as martyrdom. Ozturk’s father went on to say that when his sons were young he brought back Islamic books from Libya where he was working, and that he tried to pass on his religious convictions. Ismail took his upbringing to heart and went to Bosnia, but the war ended two or three weeks after his arrival. He returned to Turkey changed and even more committed to jihad. He later tried to join the conflict in Chechnya, but was turned back by Russian preventative measures. After these failures, Ozturk decided try his luck in the Ogaden. This time, however, his father allegedly tried to convince him to stay and get married, demonstrating the at times shifting nature of familial support for such activities.

The Bosnian Connection

The conflict in Bosnia appears to have served as a central bridge to the Ogaden, with many fighters meeting there and deciding their next destination. One figure who seems to be especially important as a link between Bosnia and the Ogaden is Atilla Saltan. A young man from Agri in eastern Turkey, Atilla eventually got a job in advertising in Istanbul. While there, he became engaged in the study of the Quran and other religious activites, eventually leaving his job. He moved to Germany, staying with family and decorating a local mosque. His apparent motivation was to make his way to Bosnia to fight, arriving there in November 1995. When the ceasefire came into effect on 14 December 1995, however,

The Clear Banner: Belgian Fighters In Syria and Iraq – November 2014

NOTE: For prior parts in the Clear Banner series you can view an archive of it all here. Also for earlier updates on Belgian foreign fighters see: September 2013, January 2014 I and II, and May 2014.

—

Belgian Fighters In Syria and Iraq – November 2014

By Pieter Van Ostaeyen

Some demographics:

Islam is the largest minority religion in Belgium, it is estimated that about 6% (about 630.000 people) of Belgium’s total population are Muslims. In the 1960’s, when Belgium still was recovering from the total devastation of World War II, the country invited thousands of Moroccan and Turkish immigrants to work in the heavy industry which at that time dominated the Belgian economy. Most of these unschooled people had relatively well-paid jobs in the steel industry or coal mines. The guest-worker program was abolished in 1974, yet a lot of these people stayed in Belgium and brought in their families taking use of the family reunification laws. Today the Muslim population keeps on growing due to marriage migrations.

In 1974 Islam was officially recognized by the Belgian government as a subsidized religion; from 1996 onwards the Belgian Muslim community has been represented by the Muslim Executive of Belgium.1 Although this first generation of Muslims seems to have integrated quite well in Belgium, this surely doesn’t stand for their children and grandchildren. Cities like Antwerp, Mechelen, Vilvoorde, and Brussels now have important minorities of descendants of these guest-worker immigrants. As such one would say this isn’t problematic at all, taking into respect on how their parents and grandparents managed to build a career and family.

However, in the 1980’s and 1990’s Belgium started facing increasing problems and mishaps with its Muslim immigrant community. Cities like Mechelen in the 1990’s were known as hubs of petty theft and drug dealing (especially by Moroccan Berbers dealing hashish). More and more of these youngsters were cruising the city with expensive cars like BMW’s and Mercedes’s. It was commonly known these cars were paid with drug-money. At that time, the city of Mechelen was referred to as ‘Chicago at the river Dijle’2, due to its extreme crime rates. Other Flemish cities were facing the same problem. In Antwerp the district of Borgerhout was known as Borgerokko because of its high amount of inhabitants from Maghrebi origin. Brussels, Belgium’s capital, had entire no-go zones. It is in this climate of fear and mutual mistrust that extreme right wing parties like Vlaams Blok (now Vlaams Belang) thrived. On the federal elections of Sunday November 24th, 1991, out of the blue Vlaams Blok gained around 6.5 % of the votes. The tone of voice was set for the years to come; using slogans like ‘adapt or get lost’, Vlaams Blok profited highly from the general mistrust amongst the Belgian public towards the Muslim community.

In the course of the next few years Vlaams Blok started building up its anti-Islamic theme, criticizing Muslims on head scarves, the slaughter of sheep on ‘Eid festivities and the fact they didn’t manage to integrate in our society. They easily disregarded the fact it was mainly because of political parties and narratives as their own that the Muslim society in Belgium had little or no chance to assimilate or let alone integrate. In the course of the next few years Vlaams Blok was forbidden and reappeared as Vlaams Belang. As such the name was dropped but the rhetoric remained the same; intolerance and latent racism in Flanders grew steadily.

It should be noted that well before Belgium was confronted with its huge amount of fighters engaged in the war in Syria (and later Iraq), the country already was a main supplier of Jihadist Fighters. On September 10th, 2001, the suicide attack on Ahmed Shah Masoud, leader of the Northern Alliance in Afghanistan was conducted by a Belgian Muslim. And even before 9/11 Belgians played a quite important role in international Jihad. Several Belgians were engaged in GICM (Groupe Islamiste Combattante Marrocaine) and GIA. Shaykh Bassam al-Ayashi, the oldest Belgian fighter in Syria, who once was suspected to be a main al-Qaeda recruiter now is leading his own little branch of Suqur as-Sham in Northern Syria.

As one of the main reasons for all, these Belgians involved all refer to the Belgian policy on its inaptitude to integrate the Muslims in our democratic society. These guys don’t see us as being democratic; they rather see how Muslims are being oppressed on what they consider to be their basic rights. The fact that Belgium forbad the face-veil or Niqab, headscarves are forbidden in schools and in public service, next year private Halal-slaughter will no longer be allowed, and so on. It is a message even confirmed by Sharia4Belgium’s spokesman Fouad Belkacem. In a statement he recently published from prison, he states: If I look back upon these days I think about the arrogance and the deep-rooted islamophobia of the Belgian State […] The head-scarf ban in 2009 hit us like an atom bomb […] For almost 50 years we saw humiliated Muslims beg for basic rights […].3