NOTE: For prior parts in the Hizballah Cavalcade series you can view an archive of it all here. This piece is part of Hizballah Cavalcade’s “Pearl & The Molotov” sub-series on Bahraini Shia militant groups.

—

Saraya al-Karar: Bahrain’s Sporadic Bombers

By Phillip Smyth

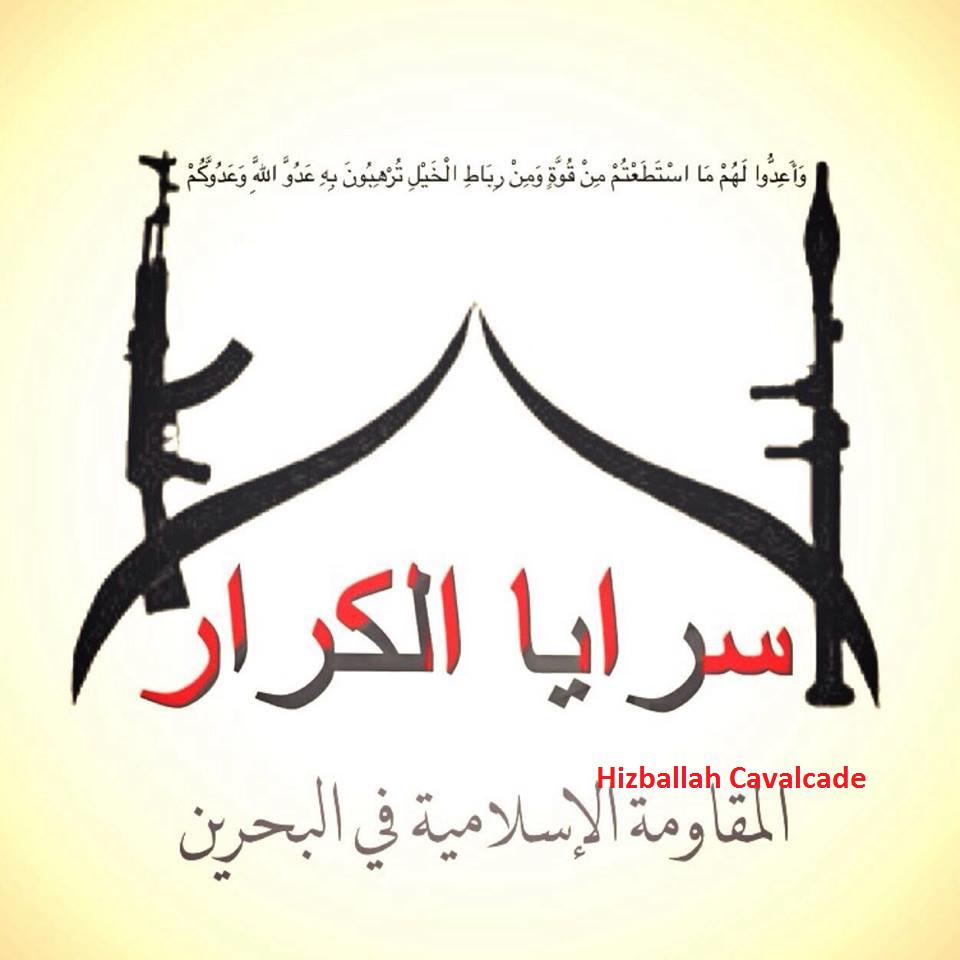

Figure 1: Saraya al-Karar’s newest logo. This symbol was first used in mid-August 2014.

Along with a number of other Bahraini Shia militant organizations, Saraya al-Karar (SaK) came onto the scene in early 2014, announcing itself via the creation of a Facebook page and a Twitter account. At first, SaK mirrored other declared militant groups like Liwa ‘Abis—Smaller than other groups, possibly a front, not as well established, and it appeared likely (as with what happened with the aforementioned organization) that after an initial wave of activity, the group would fade into obscurity. Additionally, the organization initially appeared to be either a front-group for other more established Bahraini militant groups like Saraya al-Ashtar or Saraya al-Mukhtar. While the links to those groups and what appears to be a growing public alliance between them is in the footing, the group has continued its periodic bombing campaign.

Weapons and Operations

The weapons systems SaK prefers to deploy appear to be improvised explosive devises (IEDs). Additionally, their targets have been, almost exclusively, Bahraini police officers. In general, this fits a model witnessed with other Bahraini militant groups, which have primarily targeted internal security forces.

SaK’s first round of bombings began with an announcement on February 13, 2014. The next attack occurred over a month later in March, when the group claimed an attack against a vehicle. The following attack launched by SaK occurred a month after their claimed attack on a vehicle; this time SaK claimed to target Bahraini “troops.” In both attacks, no casualties were claimed. Once again, a month later another attack was announced.

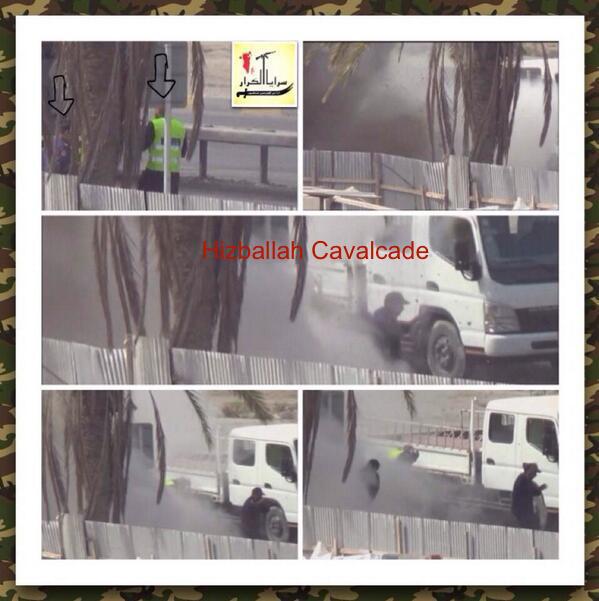

Figure 2: SaK’s July bombing photos (posted on July 8, 2014).

Figure 3: Another July SaK bombing photo series (posted on July 14, 2014).

After SaK claimed attack in late-May, the group appeared to go quiet. However, beginning in July, 2014, the organization began a renewed bombing campaign. As before, the organization targeted Bahraini police. However, unlike previous events, SaK released a series of images throughout their social media apparatus. Throughout July, a number of what appeared to be video captured photos were pieced together and posted by the group. The last of these images was for a bomb targeting a police deployment in Al-Qurayyah. Later in August, a video was posted online showing the Qurayyah attack.

Figure 4: Posted video captures from the SaK August bombing video. This photo set was posted on July 26, 2014.

However, the posting of the video (posted here) did not initially occur on an official account belonging to Saraya al-Karar. In fact, SaK, using other social media platforms, published two video versions of the attack. Neither of these clips featured the group’s logo. However, one of the clips and the main re-edited video both included the instrumental sections from Hizballah singer/songwriter Ali Barakat’s “Nasheed Faylaq Badr al-Iraq” (The song of Iraq’s Badr Corps).1 It is important to note that other Bahraini militant organizations have utilized Iranian proxy produced militant songs for their own productions. What level of connection this shows, if any, between SaK and Iran and/or their proxies are unknown.

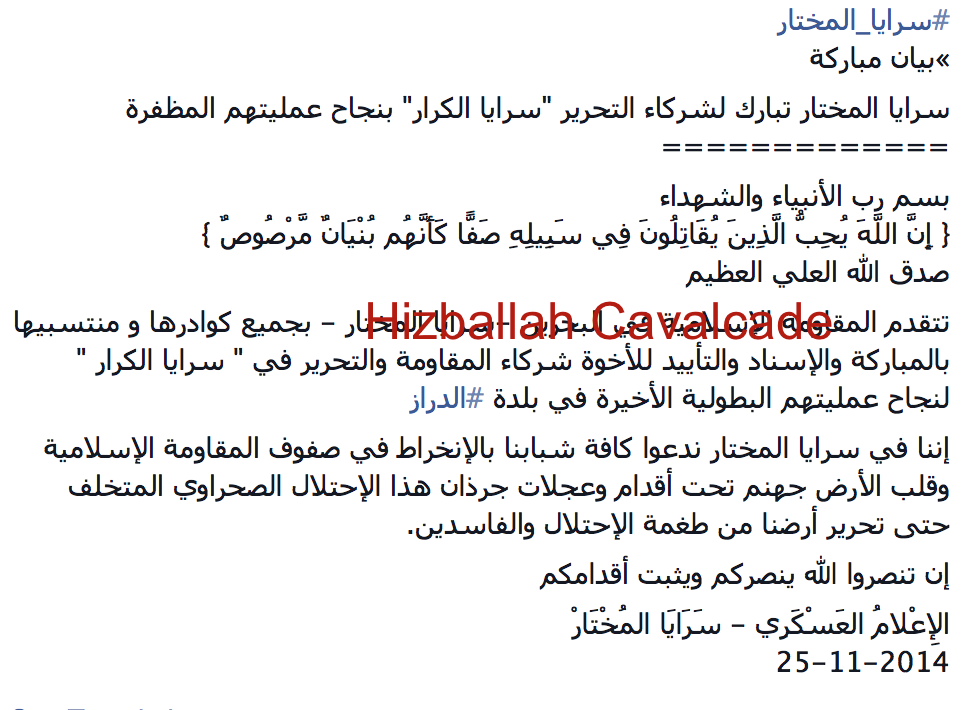

At the time of this writing, the most recent SaK attack occurred in November in the Bahraini town of Diraz. The bombing reportedly wounded two Bahraini police officers.2 The operation marked another small public turning point with Saraya al-Mukhtar praising the operation via a communiqué.

Figure 5: Saraya al-Mukhtar’s praise for SaK’s November operation that wounded 2 Bahraini police officers.

While other Bahraini militant organizations marched in lockstep in regard to their opposition to the Saudi trial and death sentence for radical cleric, Ayatollah Nimr al-Nimr, SaK has made little mention of the religious leader in recent months. However, on August 8, 2014, the group claimed an attack using a firearm in Bani Jamra. The attack was listed as, “Al-Nimr khat al-ahmar” or “the Nimr red line.” The use of the term, “red line” in relation to Ayatollah Nimr’s imprisonment and trial has been a common phrase used by other Bahrani militants.

Figure 6: SaK’s August 8 attack claim.

Symbolism & Saraya al-Karar’s Vocabulary

Figure 7 (Left): Saraya al-Karar’s first logo. This symbol was used by SaK from February-July 2014. On the left is a Kalashnikov-style rifle and on the right is what appears to be an RPG-7 type weapons system.

Figure 8 (Right): Saraya al-Karar’s second logo. This symbol, adopted in early July 2014, formed the basis for the current symbol.

SaK’s logo and presentation has seemingly become more professionalized than when the group was first announced. Initially, SaK’s symbol featured an RPG-7 and a Kalashnikov-type rifle flanking a stylized dome over the group’s name. Nevertheless, by the summer of 2014, the group set about changing its imagery into a more Hizballah-style logo with features found on the symbols of other Bahraini militant groups. First, a large red map of Bahrain was added to the logo, along with the fist-clenching-Kalashnikov (emerging from the alif in Al-Karar); a ubiquitous addition to most Iranian proxy group logos. SaK’s logo also received the addition of a Dhualfiqar-style bifurcated sword.

Mirroring other Bahraini militant groups and Iran’s proxies, Saraya al-Karar refers to its fighters as “Rijal Allah” or “Men of God.” Additionally, the SaK has called itself “Al-Muqawama al-Islamiyyah fi Bahrain” (The Islamic Resistance in Bahrain), as have the other Bahraini militant organizations. Like other Bahraini militants, the group calls their foes (Bahrain’s internal security services and police), “mercenaries.” This is a reference to non-native Bahraini individuals (often from the Arab World and the Indian subcontinent) who have joined the state’s security apparatus.

Conclusion

Thus far, SaK has not directly threatened the U.S., other Western, or Saudi interests in Bahrain. However, its public messaging and targets appear to be linked to Bahrain’s other militant groups. It is possible SaK is another Bahraini front group. Nevertheless, its continued operations appear to be establishing an independent identity for the organization. SaK attacks may continue to strike Bahraini security forces. Yet, only time can tell whether SaK will carry out future operations against other targets.

NOTES:

___________

1 See: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GYr-kdQeph8.

2 See: https://www.policemc.gov.bh/en/news_details.aspx?type=1&articleId=24462.

Category: Saraya al-Ashtar

Hizballah Cavalcade: Singing Hizballah’s Tune in Manama: Why Are Bahrain’s Militants Using the Music of Iran’s Proxies?

NOTE: For prior parts in the Hizballah Cavalcade series you can view an archive of it all here.

–

Singing Hizballah’s Tune in Manama: Why Are Bahrain’s Militants Using the Music of Iran’s Proxies?

By Phillip Smyth

Figure 1: A screenshot of a Hizballah musical band performing at the 2013 “Resistance and Liberation Festival”

Bahraini officials have repeatedly accused anti-government militants and protesters in the country of being supplied, trained, and supported by Iran and its numerous regional proxies. Still, the government of Bahrain has done little to bolster their claims of deep and intrinsic links between Bahraini militants and Tehran. Along with official Iranian denials, the issue of Iran-Bahraini militant links is still quite hazy. Nonetheless, this does not mean that within the material released by Bahraini militant organizations that there are not hints of some level of Iranian influence. One of the more intriguing pieces pointing to influence from Iranian-backed organizations comes from the utilization of specific types of music in the many propaganda videos released by Bahraini militants, their sympathizers, and amplifiers.

Numerous instances of Bahraini militants producing propaganda videos with different varieties of music created and utilized by Iranian-backed proxies could indicate a connection with Iran’s proxies. Nevertheless, this type of overlap should not be viewed as a “smoking gun” affirming Iranian involvement. However, it does assist in piecing together direct and indirect influences.

The pieces of music in question were originally developed and used by Iranian proxy organizations, particularly Lebanese Hizballah, Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq (AAH), and Kata’ib Hizballah. In fact, some of the songs that have been promoted fit a long standing media strategy employed by the aforementioned groups and Iran when manufacturing narratives and perceptions for themselves and other armed groups.

The use of music as a transferable propaganda medium follows a very formulaic strategy used by Iran and its “Islamic Resistance” proxy organizations for many years. Often, songs produced for one group are repackaged for newer organizations in other geographic locations. The songs are then altered in a way to make them appeal to the populations and target audience where the new group is located.

Possible Reasons for Using Specific Songs

Why would Bahraini militant groups utilize Hizballah and its Iraqi clones’ music and with such frequency? Some possible answers include:

- Direct Iranian influence or assistance provided to the developing militant groups.

- Video editing/production was offered to Bahraini militants by Iran and/or its proxies as a means to influence and shape militant organizations and to encourage the adoption of a more bellicose strategy to the broader (and more peaceful) protester audience.

- Bahraini militants sympathize with Iranian-proxy groups, their exploits, and with the general concept of “Al-Muqawama al-Islamiyya” (“The Islamic Resistance”). The hope to be as successful, feared, and/or respected as those organizations has led them to adopt the same varieties of music.

- Thumbing their nose at the government: With the government of Bahrain accusing protesters and militants of being Iranian proxies, militant groups may use the material as a way to subtly frighten or encourage speculation among Bahraini government and other observers.

- Narrative Goals: One song by Lebanese Hizballah’s Ali al-Attar called “Wa’ad al-Asra” or “The Prisoner’s Promise” was written to celebrate the release of prisoners Hizballah sought to free during the 2006 Hizballah-Israel War. While the song makes clear references to Lebanese Hizballah and themes related to the 2006 war, the same song was employed by some Bahraini protesters (as background music for their uploaded clips) when they protested the government’s detention of key protest-leaders.

Auto-Tuning the Revolution: Examples of the Musical Overlap

In March 2014, a music video which was claimed to have been produced by “Saraya al-Bahrainiyya al-Muqawama” or the Bahraini Resistance Brigades, (which is likely another name used by The February 14 Youth Coalition’s Saraya al-Muqawama al-Sha’biya [Popular Resistance Brigades]) was posted by the popular Revolution Bahrain’s YouTube Channel. The video featured a montage of edited clips, which purported to show Bahraini militants engaged in training. The music video also included a number of videos of bombings orchestrated by militant Bahraini organizations.

Yet, the music used was strikingly familiar in the circles of Iranian-backed Shi’a Islamist groups. In fact, Iranian-backed Iraqi group, Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq had released the exact tune back in 2011 to commemorate attacks the group orchestrated against U.S. targets to demonstrate solidarity with Bahrain’s protesters. Later in 2011, when fellow Iranian proxy Kata’ib Hizballah released footage of attacks it had also launched in solidarity with Bahraini protesters, it too used the same song.

However, the song was neither originally Bahraini nor Iraqi, instead its origins were rooted father to the west, in Lebanon. The original song, “Risalat al-Thuwar” (“Message of the Rebels”), was performed by one of Lebanese Hizballah’s official bands, Firqat al-Fajr (The Dawn Band), following the 2006 Hizballah-Israel War. It first appeared on the band’s 2007 “Lahan al-Turab” or “Melody of the Soil” album. Still, the rendition dealing with Bahrain was not the only version of the song. Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq had their own Iraq/Grand Ayatollah Muhammad Muhammad Sadiq Sadr (as opposed to Sayyid Hassan Nasrallah) themed “Risalat Thuwar” produced in 2011.

“Risalat al-Thuwar” is not the only Hizballah song which has been adopted and rebranded by Bahraini militants and their amplifiers. Another song used by Bahraini militants also comes from Firqat al-Fajr. The song, “Ya Wa’ad Allah” (“O Promise of God”) can be found on the group’s 2008 album, “Sharit Wa’ad Allah” (“Take the Promise of God”). The song has been released in different formats, with more recent music video varieties showcasing the assassinated Hizballah terror-mastermind Imad Mughniyeh. The album also included an instrumental version of the song. Both versions have been prominent features on productions done by Hizballah’s Al-Manar TV network.

In Bahrain, “Ya Wa’ad Allah” was used as background for clips released to the popular (particularly with militant groups) Revolution Bahrain’s YouTube account. One of these videos included the firebombing of an armored car used by Bahraini government forces.

It is not just the polished music video-quality material finding its way into Bahraini militant propaganda productions. Bahraini militant group Saraya al-Mukhtar released a video of their April 2014 targeting of Bahraini police with an improvised explosive device. Another bomb attack in Bani Jamra also utilized the same background music.

The musical selection in the background matched with instrumentals used by Iraq’s Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq. This music was first featured on the AAH-affiliated Al-Ahad TV in the late summer/fall of 2013 to commemorate Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq members killed fighting in Syria. Further pointing to some level of Iranian or Iranian proxy influence, is highly unlikely that this particular musical element could find its way into so many pieces of released footage. This may indicate some Bahraini militant footage being sent abroad (possibly to Iraq) where the footage is re-edited and put back together for a later introduction.

Another similar instrumental used by Bahraini militants with Saraya al-Mukhtar and Saraya al-Ashtar was also the same exact tune utilized in a number of Kata’ib Hizballah video releases (see: 00.17-00.40 on “Kata’ib Hizballah Anti-America Video”).

The use of the last two instrumentals create further questions. Why would these groups, which have resorted to using a variety of improvised weapons, and exist under increasing heavy security crackdowns, spend the time to find, edit, and utilize background instrumentals which already have obscure points of origin. Why pick these two exact instrumentals, which have only been found in the repertoire of Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq and Kata’ib Hizballah? Other Bahraini protest organizations have utilized a variety of different musical accompaniments. Thus, the use of these particular musical pieces seem out of place when compared to the rest of what has been released.

Whatever the reasons, closely assessing the propaganda published by these organizations may provide insight into rather opaque organizations. While assessing the musical selections may appear to be a tangential escapade, AAH, Kata’ib Hizballah, and Lebanese Hizballah have all demonstrated their strategy of using this material as another method to push the narrative of the “Islamic Resistance.”

Hizballah Cavalcade: Asa’ib al-Muqawama al-Bahrainia: An Emerging Militant Group in Bahrain?

NOTE: For prior parts in the Hizballah Cavalcade series you can view an archive of it all here.

—

Asa’ib al-Muqawama al-Bahrainia: An Emerging Militant Group in Bahrain?

By Phillip Smyth

Figure 1: Asa’ib al-Muqawama al-Bahrainia’s logo.

Asa’ib al-Muqawama al-Bahrainia (The League of Bahraini Resistance or AMB) was first established and marketed as an independent militant organization on February 22, 2014. The group’s founding announcement claimed that the time had become ripe for armed opposition against Bahrain’s ruling monarchy due to the government’s actions. As with other Bahraini militant groups, little is known about AMB’s manpower or armed capabilities.

Regardless, unlike other Bahraini militant organizations, AMB’s founding announcement has found its way onto many different online venues catering to a wide range of readers.[1]

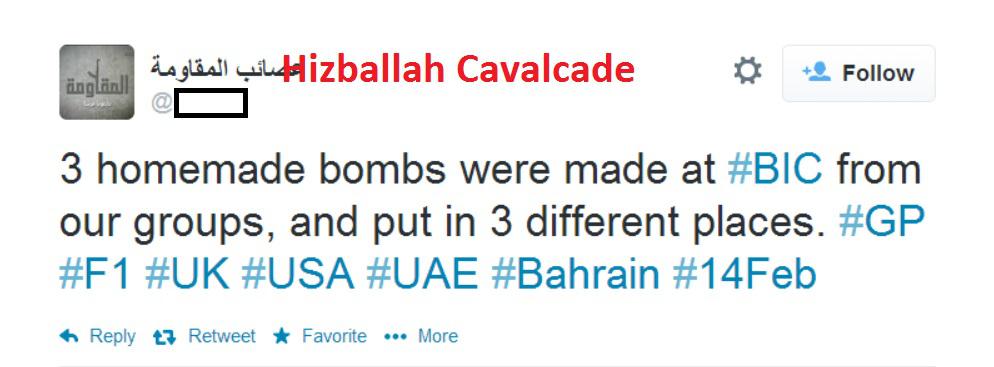

AMB’s statements appear online in bursts. February 22 and February 28, 2014 have been the two dates this organization has placed a series of announcements in public. This pattern is reminiscent of another Bahraini organization, a proto-militant group which went by a similar name, Asa’ib al-Muqawama (The Resistance League). Using Twitter, Asa’ib al-Muqawama released 33 announcements (in both Arabic and English) between April 21 and 22, 2012. Asa’ib al-Muqawama’s threats centered on Bahrain’s controversial Formula One race. One of these statements claimed responsibility for planting three homemade bombs at the race location. At time, there were also instances of Molotov cocktails being thrown at some (from Team India) affiliated with the race.[2] Additionally, on April 9, 2012, seven Bahraini police were wounded due to an improvised bomb planted in the town of Akr.[3] Albeit, neither of these attacks were linked to Asa’ib al-Muqawama.

After their last tweet on April 22, 2012, Asa’ib al-Muqawama went quiet. This is similar to how AMB went silent after their last February 28, 2014 statement. There is a possibility of a link between AMB and Asa’ib al-Muqawama, considering the groups espouse the same militarism, utilized a similar name, and have released announcements in bursts over two-day periods. In fact, AMB’s official Twitter account also describes itself as “Asa’ib al-Muqawama.” It is possible that AMB developed out of the original Asa’ib al-Muqawama. However, beyond these assumptions, there is little substantiating open-source information to assist in confirming any links.

Figure 2: Asa’ib al-Muqawama’s English language Tweet-announcement, declaring they had planted 3 bombs at the Bahrain F1 race.

Figure 3: Asa’ib Muqawama’s logo.

Figure 4: AMB’s first announcement.

On February 28, 2014 AMB announced the launch of their, “Fist of Righteousness” operation to avenge the death of Ja’afar al-Derazi. Derazi, whose burial occurred the day of the announcement, was a 22 year old anti-government activist. According to opposition and pro-Iran sources, Derazi died due to torture and other forms of maltreatment when he was detained within a government jail cell.[4] In revenge for Derazi’s death, on April 11, 2014, Saraya al-Mukhtar claimed responsibility for an attack targeting Bahraini police. Nevertheless, AMB has not yet claimed any other attacks as part of their “Fist of Righteousness” campaign.

Figure 5: AMB’s second announcement from February 28, 2014.

AMB Joins YouTube

AMB’s official YouTube account claimed to release a video introducing the group on February 21, 2014. However, the first publicly accessible copy of the video was uploaded and released on February 22, 2014. In the video, supposed AMB members are shown marching in formation, extending their arms in a Roman salute. Demonstrating their potential roots as militant offshoots of the larger Bahraini protest movement, young balaclava wearing men hold tires in one of their displays. Tires are a regular feature in some protests; often laid across stretches of road, coated in gasoline, and lit on fire.

Furthering religious themes was also a feature of the film. Young marching militants are seen holding Qurans, wearing white (in addition to other colors) burial shrouds symbolizing a willingness to be martyred, and holding flags with “Ya Husayn” (“O Husayn”) written on them. The “Ya Husayn” flags symbolize a Shia-centric theme, recalling Husayn’s martyrdom via beheading, at the pivotal Battle of Karbala.[5] These flags have also made regular appearances during anti-government protests.

The promotional clip also claims to show AMB launching operations against internal security elements (primarily the Bahraini police). Segments of film featuring Molotov throwing youths are a main theme. However, these clips are usually from earlier films recorded by more violent activists associated with the February 14 Youth Coalition. It is possible this footage demonstrates a further link to the February 14 Youth Coalition or it was simply repackaged by AMB to show a broader theme surrounding the “resistance” against the Bahraini government and their forces.

AMB also appears to have a preoccupation with utilizing weapons which can burn their foes. This may be the result of protester use of Molotov cocktails. Utilizing the limited available tools, some Bahraini protesters, particularly younger male militants, have often thrown Molotov cocktails at Bahraini internal security forces. The theme of the Molotov thrown at Bahraini police, particularly their vehicles, was regularly utilized in AMB’s introductory video. However, the focus on using weapons which can kill and injure using fire does not appear to stop with Molotovs. In one part of their video, AMB shows Bahraini police engulfed in a wall of flame, likely caused by a bomb or another incendiary device.

AMB’s Badge

AMB’s logo may also show links to Saraya al-Ashtar (SaM), one of the first publicly established Bahraini militant organizations. Featuring two crossed M16-style rifles within a circle (which could potentially symbolize a pearl, a recognized emblem of Bahrain), the group’s logo mirrors SaM’s official symbol. This logo also included two crossed rifles (albeit, of the Kalashnikov variety) within a circle representing a pearl.

An Asa’ib of Their Own?

When investigating potential links between AMB, Iran, or Iranian-backed proxies, there was some evidence of overlap between AMB & Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq (AAH). On March 13, 2014, AMB’s founding statement was circulated on AAH’s extensive network of Facebook pages. This often coincided with claims that AMB was representative of AAH’s spreading brand. Claims of this nature may be an Iranian proxy attempt to demonstrate a substantial link to the Bahraini militant group. Both groups utilize similar language, with AMB describing itself as the “Bahraini Resistance” and AAH calling itself the, “Islamic Resistance in Iraq.” Still, there is the possibility that AAH could be jumping on an organically constructed (in Bahrain) group while skillfully playing on AMB’s similar name, all in an effort to claim a connection and demonstrate a broader reach. It is important to note that it took AAH nearly a month before pages associated with the group started to carry AMB’s founding statement.

Another potential link includes religious and ideological themes. The AMB’s founding statement mentioned the group was following their taklif. A taklif, or religiously mandated order, was developed and utilized for political and social events by those embracing Iranian Islamic Revolutionary concepts.[6] The mention of a taklif mirrors a similar statement made by fellow Bahraini militant group, Saraya al-Mukhtar, which also mentioned they were picking-up arms against the government due to a taklif.

Figure 6: A post promoting the first AMB declaration on an official Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq Facebook page.

Is AMB Dormant?

At the time of this writing, the last statement issued by AMB was released via their Twitter account on February 28. Since that time, AMB has not itself claimed any new attacks, seen related militant groups, protest organizations, or the official Bahraini media, cite any new actions by the group. While little has been heard from this organization since it’s nearly 2 month-long period of silence, AMB’s release of formal statements, broad web-presence (including their YouTube video release), overlap between itself and other Bahraini militant groups, and other attack claims, may indicate AMB is still active.

AMB’s activities may be continuing as members of the organization act as integral elements within other Bahrain militant groups. If there is a true link between the AMB and Asa’ib al-Muqawama, it is possible that following the established model, a new wave of attack-claims could be registered on an entirely new online/social networking apparatus.

Nevertheless, until AMB claims another attack or has an allied organization claim an attack for them, it will be impossible to know what has become of this group

_____________

[1] Note: Numerous Sunni Islamist and Shia Islamist forums, Facebook

Hizballah Cavalcade: Bahrain’s Saraya al-Muqawama al-Sha’biya: Militants of the February 14 Youth Coalition

NOTE: For prior parts in the Hizballah Cavalcade series you can view an archive of it all here.

—

Bahrain’s Saraya al-Muqawama al-Sha’biya: Militants of the February 14 Youth Coalition

By Phillip Smyth

Figure 1: Saraya al-Muqawama al-Sha’biya’s logo.

Saraya al-Muqawama al-Sha’biya (The Popular Resistance Brigades or SMS), sometimes also called Saraya al-Muqawama (The Resistance Brigades), was listed by the government of Bahrain as a terrorist organization following the deadly March 3, 2014 bombing. The group, along with fellow militant group Saraya al-Ashtar, claimed responsibility for the attack. SMS has been operationally active and publishing its activities online since April 2012. Importantly, Saraya al-Muqawama al-Sha’biya does not hide that they are affiliated with one of the main anti-government protest groups, the February 14 Youth Coalition (which was also listed as a terrorist organization by the government of Bahrain). This is hardly a minor connection, since, both the February 14 Youth Coalition and SMS have also distributed images sharing one another’s logos, organized events (such as protests) together, and share a similar narrative. Other militant groups—namely Saraya al-Ashtar and Saraya al-Mukhtar—have only vaguely claimed to represent links to protestors, let alone main protest organizations.

In June 2013, the Bahraini government accused the February 14 Youth Coalition of having a “spiritual leader” based in Karbala, Iraq and of, “frequently travel[ing] between Iran, Iraq and Lebanon to obtain financial and moral support as well as weapons training.” However, Bahraini authorities provided little substantiating evidence dealing with claims of Iranian or Iranian proxy involvement. Nevertheless, according to Iranian reports, February 14 Youth Coalition representatives have thanked Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei for his comments supportive of their activities. Iranian media has also expressed their support for the “revolutionary activities” of the Bahraini group. Despite these pronouncements, the actual relationship between Iran and the February 14 Youth Coalition, particularly dealing with any attempts at training or equipping militant elements attached to the organization, is still unknown.

Figure 2: Both the February 14 Youth Coalition and Saraya al-Muqawama al-Sha’biya’s logos on a promotional image released onto multiple February 14 Youth Coalition pages.

Figure 3: SMS supporters carry the group’s flag during a march.

Figure 4: SMS and February 14 Youth Coalition supporters march together and carry February 14 Youth Coalition flags.

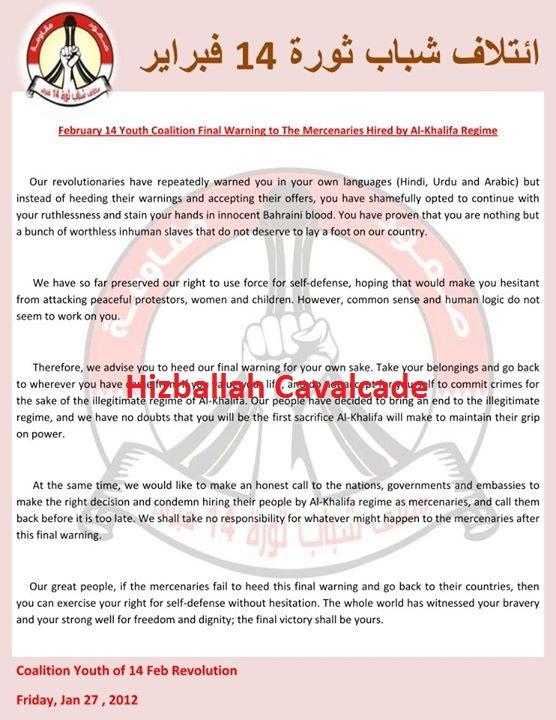

Initially, the February 14 Youth Coalition did not embrace violence. However, after publishing a series of “warnings” to the Bahraini government, Gulf Arab states (namely, Saudi Arabia and the UAE) which have deployed forces to Bahrain, and foreigners recruited into the Bahrain’s internal security forces (often referred to by the group and other Bahraini militants as, “mercenaries”), the coalition issued communiques demonstrating they would choose a more militant path of “resistance.” In a January 27, 2012 English-language statement made by a February 14 Youth Coalition affiliated page, the group issued a statement reading:

“We have so far preserved our right to use force for self-defense, hoping that would make you hesitant from attacking peaceful protestors, women and children. However, common sense and human logic do not seem to work on you…Our people have decided to bring an end to the illegitimate regime…We shall take no responsibility for whatever might happen to the mercenaries after this final warning.”

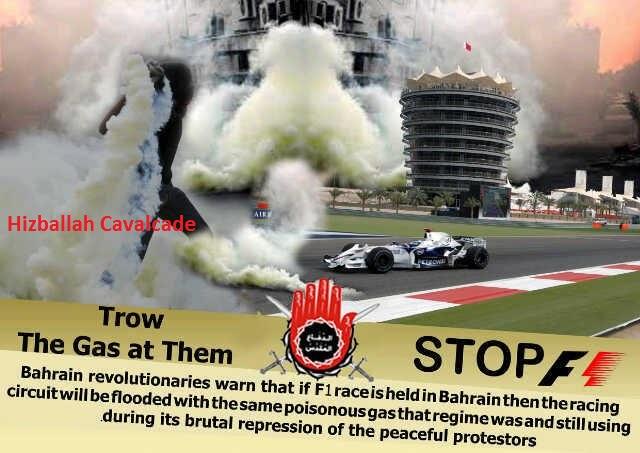

Three months after this announcement, SMS pushed for a response to the holding of the controversial 2012 Bahrain Grand Prix Formula 1 race. The group released images urging protestors to throw the gas (the group claimed it was poisonous) used by Bahraini police at the race cars. However, no armed action was taken against the race by SMS. It is likely that in such an early stage of development and combined with Bahraini government crackdowns, the group was unable to act.

Figure 5: One of SMS’s English language posters calling for action against the 2012 Grand Prix race.

Narrative Structure

SMS considers its fighters to be “jihadists,” refer to their attacks as “jihadist operations,” and believe they are fighting a “jihad against the infidel Khalifas [Bahrain’s ruling royal family].” While the message of jihad is repeated in many SMS statements, these statements do not share the same level of more complicated religious and ideological messaging found with other non-Bahraini Shia jihadist elements.

SMS also lacks a specific goal for what type of government will rule in Bahrain following a theoretical collapse of the currently ruling Khalifa royal family. Still, this has not stopped the group from constructing complex narratives via militant activity for their enemies.

Following Saraya al-Ashtar’s and SMS’s claim of responsibility for the March 3, 2014 bombing (which killed two Bahraini police officers and a police officer sent by the United Arab Emirates [UAE] to Bahrain), SMS used the opportunity to criticize government claims that forces of the Peninsula Shield Force were being used in conjunction with local Bahraini police forces to counter protests and riots.

Sent to Bahrain in 2011, the Peninsula Shield Force included hundreds from the Saudi military and the UAE’s police force. Officially, these units claimed they were not involved in internal matters in Bahrain and were only interested in securing strategic bases and locations from “external influence.” Regardless, the death of a UAE police officer attached to Bahraini police served as a propaganda coup for SMS.

The timing of the SMS’s bombing claim and messages which proceeded it also fit into a broader message dealing with the Peninsula Shield Force and particularly Saudi Arabia. SMS has demonstrated a specific ire for the Saudis. The organization’s communiques have called Saudi Arabia the “usurper of land,” “occupiers,” and have stated their operations are to “purge the land of its Saudi and Khalifa occupiers.”

In part, this may tie back to February 14 Youth Coalition links to Saudi Shia activists. Researcher Fredric M. Wehrey noted that an “important attribute of the February 14 Youth Coalition is its strong affinity with Shi’a activists in neighboring Saudi Arabia.” Wehrey went on to explain how coordinated protests were conducted by Bahraini and Saudi groups out of solidarity. The February 14 Youth Coalition’s and SMS’s links to the Saudi Shia is also important when viewed in context with announcements by fellow militant organization, Saraya al-Mukhtar. Saraya al-Mukhtar has issued a number of announcements saying they share the cause of the “people of the [Saudi] Eastern Region” –an area heavily populated by Saudi Shia. The shared narrative may demonstrate deeper links between Saraya al-Mukhtar, SMS, and the February 14 Youth Coalition.

Figure 6: A poster released by the February 14 Youth Coalition asking, “Who are the terrorists?” The photo shows Saudi forces crossing the King Fahd Causeway which links Bahrain to Saudi Arabia.

As part of the view casting the Saudis as foreign occupiers, activists from SMS and the February 14 Youth Coalition have drawn parallels between Israel and Saudi Arabia; accusing both counties of using the same techniques of occupation. Prior to a series of March 2014 protests against “Saudi occupation”, the February 14 Youth Coalition and SMS circulated images attempting to link Saudi Arabia and Israel as fellow occupying states. This also extended into the realm of February 14 Youth Coalition partisans attempting to directly link the causes of Palestinian and Bahraini demonstrators.

Figure 7: The Israeli flag flies behind Jerusalem’s Dome of the Rock (left) while a bulldozer is shown destroying the 400 year old Amir Mohammed Braighi Mosque with a Saudi flag behind it (right). The latter incident occurred in 2011 along with the Bahraini government destruction of other Shia mosques. This picture was used as a tool to organize activists for protests and events against the “Saudi occupation.”

Figure 8: A poster showing a Bahraini protester (with February 14 Youth Coalition) and a Palestinian activist. The former looks to the now demolished Pearl Roundabout statue, the latter looks to the Dome of the Rock. The picture attempts to show a unity of purpose and cause between Palestinian and Bahraini demonstrators.

Symbols of the “Popular Resistance”

Figure 9: SMS protesters at a February 14 Youth Coalition event demonstrating against “The Saudi Occupation.”

Shia symbolism is heavily featured in the group’s logo. The most prominent image is the symbolic hand of Shia leader Abbas Ibn Ali; son of the first Shia imam and loyal aid and military leader for the third Shia imam, Husayn ibn Ali. Serving as Husayn’s flag bearer during the historic Battle of Karbala, Abbas’s hand was cut off by one of the forces of Yazid, the reviled leader of the Umayyads, as Abbas went alone to collect water for Husayn’s dehydrated camp. Abbas went on to fight singlehandedly until his other arm was cut off by sword strikes from Yazid’s forces and was then killed. Abbas’s loyalty and steadfastness until being cut down remains an important message for many Shia Muslims.

Another unique feature from the logo is that “The Sacred Defense” is written within the symbolic hand of Abbas. This helps convey that the group’s conflict with the government is viewed as both a defensive and religiously justified action. Intriguingly, the Shia jihad in Syria and the Iran-Iraq War (1980-1988) have (by Shia actors) both been described as “The Sacred Defense.”

Behind the

Hizballah Cavalcade: Saraya al-Mukhtar: A Bahraini Militant Group with Regional Goals

NOTE: For prior parts in the Hizballah Cavalcade series you can view an archive of it all here.

—

Saraya al-Mukhtar: A Bahraini Militant Group with Regional Goals

Figure 1: Saraya al-Mukhtar’s newest logo. The group’s name is on the bottom, a black zulfiqar style sword combines in with a a black roundel featuring a green fist and black barrel and forearm of a Kalashnikov-type rifle. On the left is a red map of Bahrain.

Figure 2: Saraya al-Mukhtar’s first logo. The symbol appears to show two crossed bifurcated Zufiqar-type swords resting on a book (most likely the Quran). The organization’s name appears at the bottom of the logo.

First announcing itself to larger audiences online in a September 26, 2013 statement on Facebook (albeit, the statement itself was dated September 27), Saraya al-Mukhtar (The Mukhtar Brigade or SaM) has claimed numerous attacks on Bahraini security forces and has developed a sophisticated messaging strategy. At the time, the then new group promised to strike at the ruling Khalifa royal family and their security forces with, “operations of quality”. Despite the group’s September online appearance, it still claimed attacks since the summer of 2013. These operations have primarily included the use of crudely produced improvised explosive devices (IEDs) and types of arson attacks. SaM also has the unique distinction among Bahraini militant groups for claiming their first fallen member, or “martyr”, Ali al-Sayyid Ahmed al-Musawi. The group’s narrative on both a regional and potential religious-ideological level have also set it aside from other Bahraini armed organizations.

Figure 3: Saraya al-Mukhtar’s martyrdom poster for Ali Sayyid Ahmed al-Musawi.

Save for the occasional mentions state-run Bahraini press organs and opposition reports on the situation in Bahrain, for the most part, the group has not received as much media scrutiny as militant groups such as Saraya al-Ashtar. Additionally, SaM appears to have escaped specific mention on Bahrain’s terror group list.[1]

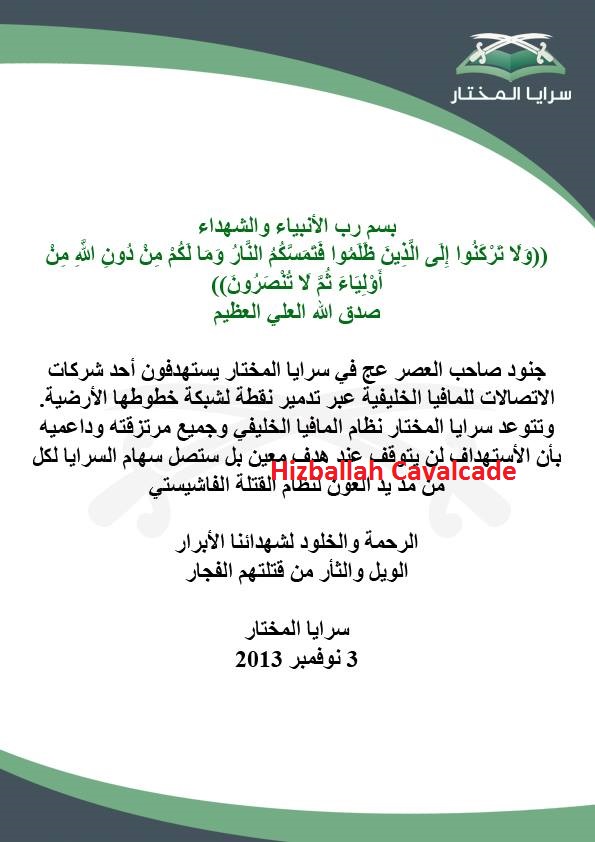

The group calls their foes; The Khalifa royal family, Bahraini security forces, and Saudi Arabia, “a mafia/the Khalifa mafia”, “mercenaries/criminals”, and “occupiers”, respectively. In a November 3, 2013 announcement, SaM vowed to “crush the fascistic regime.” This type of discourse generally fits with most rhetoric issued by Bahraini militant groups. Though, SaM appears to be a bit more colorful when describing their enemies.

Figure 4: SaM’s November 3, 2013 statement.

In terms of promoting the group’s goals, narrative, and attacks, Saraya al-Mukhtar has exhibited the most advanced strategy and online presence when compared to other Bahraini militant organizations. The group has Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram accounts, among other modes of digital communication with supporters. On March 5, 2014, the group’s main Facebook was taken offline. Another page was quickly made in its place where the group claimed “the tyrant’s mercenaries” took the last page down. On YouTube, the group (or possibly loosely-linked supporters) started separate accounts which would upload one clip of an attack the group claimed and then become inactive. It is unclear whether this is done as an operational security method or for some other purpose. As with Saraya al-Ashtar, the group has also sent footage of its attacks to popular pro-revolution YouTube stations for broader dissemination.

Shia religiously-based rhetoric is a more established common feature in SaM’s releases, rhetoric and even the group’s name. The organization also calls itself, “Al-Muqawama al-Islamiyya al-Bahrania” or the “Bahraini Islamic Resistance.” Most Iranian-backed militant organizations also use this term as a self-descriptor.[2] However, it is possible this could be an example of mimicry, demonstrating the group respects the strength of those organizations and is attempting to adopt their rhetoric to appear more powerful.

Saraya al-Mukhtar’s moniker is likely a reference to Mukhtar al-Thaqafi. Mukhtar al-Thaqafi was a figure who launched a failed rebellion against the Umayyad’s in the 7th century. The rebellion was initiated in southern Iraq and executed in order to get revenge for the death of the third Shia imam, Husayn ibn Ali, who was killed by the Umayyads during the Battle of Karbala.[3]

Interestingly, the name of the group and its background history plays into the style of media campaigns and announcements made by SaM. Often, the group brands their attacks and those launched by other groups against internal security elements as “revenge.” On January 27, 2014 SaM launched the “Vengeance Has Been Achieved Media Campaign.” Until the time of this writing, the slogan, “Vengeance has been achieved” is still stamped onto the photos of injured (often in hospital) Bahraini police.

The recruitment and naturalization of foreigners (particularly from Sunni Muslim religious backgrounds) into Bahrain’s internal security forces has been a main objection for peaceful protesters and militants alike. This is a main reason why SaM, other Bahraini militants, and peaceful protesters have referred to these internal security elements as “mercenaries.” Tapping into this grievance, SaM regularly posts images of police officers with foreign backgrounds that the group has targeted.

Additionally, the motive of “revenge” may be another attempt to appeal to some younger portions of the protest movement. Due to numerous bloody crackdowns by the government, these elements have become fed-up with more traditional groups leading peaceful protests.[4] Thus, SaM likely sees them as a component which can be brought into to give some level of support (even passive) to the organization’s activities.

Figure 5: On February 9, 2014, SaM claimed to kill Ahmed Rashid al-Moraysi, a Syrian working for the Bahraini police. “Vengence has been achieved” was stamped on the photo.

Claimed Militant Activities

Saraya al-Mukhtar has been quite prolific in the production of videos and the release of photographs to show off its attacks. In one November, 2013 attack on what the group claimed was a communications network station, photos and a video of the target being attacked (with what appears to be a crude incendiary device) were posted online.

Following Saraya al-Ashtar’s claimed March 3 bomb attack against Bahraini police, Saraya al-Mukhtar praised the, “Bahraini Resistance.” On March 5 SaM released an edited photo showing the aftermath of the bombing and praising the action.

Figure 6: Saraya al-Mukhtar’s image praising the bomb attack on March 3, 2014.

The group also claims to be in possession of a special sniper weapon they call the “Mukhtar 1”. It is unclear if the weapon is a firearm or some other improvised device. However, SaM has released video on March 4, 2014 of the Mukhtar 1 in use against Bahraini police forces. Like Saraya al-Ashtar, SaM’s videos were released through a combination of the group’s own YouTube pages.

Another uploaded Saraya al-Mukhtar video claimed to show a January IED attack against a Bahraini police checkpoint. This video was also sent into other YouTube stations in a possible effort to increase viewership.

Figure 7: A Saraya al-Mukhtar released photo claiming a January attack against “mercenaries”.

Regional Outlook & Ideology

Figure 8: Saraya al-Mukhtar’s February 20, 2014 post.

Saraya al-Mukhtar’s potential links with radical Shia Islamist ideology and the group’s regional aspirations were showcased in a small post made on their official Facebook page on February 20, 2014. The group appears to view the conflict in Bahrain as part of a larger regional conflagration involving Saudi Arabia. Their post read, “The cause of the people in the Eastern Region [of Saudi Arabia] and our defense is one…Resistance against Saudi occupation, our taklif, and our fate are united.”

The statement about Saudi Arabia’s “Eastern Region” is a direct reference to an area which not only borders Bahrain, but is main zone where much of the Saudi Shia Islamic community, 15 percent of the Saudi population, call home.[5] Saudi Shia have faced exclusion from politics, government positions, and many economic opportunities, not to mention suffering religious discrimination. Throughout 2013, Saudi Shia groups organized numerous protests—particularly in Qatif,

Hizballah Cavalcade: Saraya al-Ashtar: Bahrain’s Illusive Bomb Throwers

NOTE: For prior parts in the Hizballah Cavalcade series you can view an archive of it all here. For the first part in the subseries on Bahraini militant groups: “The Pearl and the Molotov.”

—

Saraya al-Ashtar: Bahrain’s Illusive Bomb Throwers

by Phillip Smyth

Figure 1: Saraya al-Ashtar’s main logo. The symbol shows two Kalashnikov-type rifles crossed over a roundel which resembles a pearl. The base includes the group’s name.

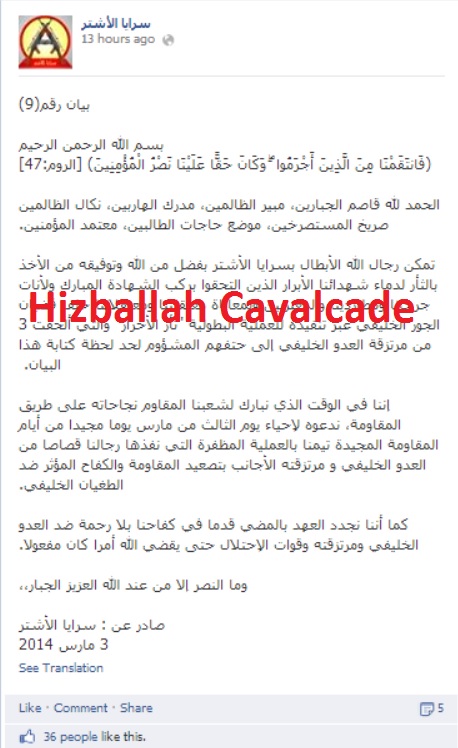

“The operation comes in revenge for our martyrs”, read the March 3, 2014 “Statement No. 9”, issued by Saraya al-Ashtar (The Ashtar Brigades or SaA) on Facebook and Twitter. This declaration directly referred to a bomb which was detonated during a Bahraini police operation in the town of Daih. Three were killed, including an Emirati officer who was deployed to Bahrain as part of the “Gulf Waves Force”.[1] Reportedly, the police were attempting to disperse what was claimed in an official statement as a “riot.” The protests occurred following funeral demos for another Bahraini protester.[2] However, the group claiming responsibly for the bombing received little attention in Western media and passing mention in Arabic language news. Regardless, the Saraya al-Ashtar group is quickly making a name for itself via it bombing campaign.

Since the summer of 2013, the group claimed almost twenty attacks against security personnel in Bahrain. The March 3 blast appears to be another attack in a long and developing list of bombings carried out by the group. This will probably not be the group’s last. On March 4, the Bahraini government listed Saraya al-Ashtar as a terrorist group.[3] Still, the organization is quite shadowy and despite Bahraini government arrests, appears to be active.

Figure 2: Saraya al-Ashtar’s Statement 9, which claimed responsibility for the bombing of Bahraini police officers.

Figure 3: A member of the Bahraini internal security forces looks at blood-stained concrete following the March 3rd blast. (Source: Facebook)

Saraya al-Ashtar released its first statement via their Facebook page on April 27, 2013 (albeit, the written statement was dated April 28, 2013). In part, it stated, “Enough is enough” in regard to the actions of, “the rabid dogs of al-Khalifa [Bahrain’s ruling royal family].” The group promised to strike their enemies the next day. Keeping to their word, on April 29 SaA claimed in another post that they had, “Targeted a collection of mercenaries [the term most Bahraini militants use to describe Bahraini internal security forces] at the Adra roundabout”.[4]

Attacks such as these have demonstrated SaA’s preferred method of operation: Building and detonating improvised explosive devices and their direct targeting of Bahraini government security personnel.

SaA has an extensive social media presence with Facebook and Twitter accounts. These platforms are used to promote the group, broadcast threats, and to claim responsibility for attacks. Nevertheless, the group has not posted any photographs of their operations, membership, or weapons systems.

In fact, SaA has not released any photographs save for their logos. With the logos come further questions. SaA’s first displayed symbol was clearly modeled off of Iranian-backed groups, most likely Kata’ib Hizballah’s logo. Their second, showing crossed Kalashnikovs over what appears to be a pearl (a national symbol for Bahrain) continues the militant theme.

Figure 4: SaA’s first logo.

Figure 5: Kata’ib Hizballah’s logo. Note the similarities between the fist-clenching-Kalashnikov images.

While photographs have been lacking, there have been a number of videos released onto the internet showing SaA’s attacks. Since the summer of 2013 the group has also posted video footage of some of the attacks it has carried out against Bahraini security personnel. One of the videos claimed to show an attack the group made in Bani Jamra, a town in northwestern Bahrain.[5] In another video from October, the group wrote, “This is just the beginning.”

Designed to coincide with the major February 14 protests (which commemorate the start of the 2011 Bahraini Uprising), SaA carried out another nighttime attack against Bahraini internal security forces and also released a film of their action. Albeit, instead of using their own accounts, this time the group sent the video to the popular “Revolution Bahrain” YouTube station. This style of release was repeated following the March 3 bombing when the group released footage it claims to have taken showing the aftermath of the bomb. In all cases, films of their attacks are regularly edited in order to give the group a level of operational security.

Following the March 3 blast, supporters of the group published clips which reportedly showed protests in support of the “holy warriors of Saraya al-Ashtar.” During the protest, candy was handed out to show support for the attack.[6]

The Rhetoric of Saraya al-Ashtar

Demonstrating a direct link to the adoption of Shia-centric forms of messaging, Saraya al-Ashtar’s name was likely no coincidence. It’s possible the group draws the roots of its name from Malik al-Ashtar, one of Imam Ali Ibn Abi Talib’s most loyal aids and colleagues. Malik al-Ashtar was also known to be a brave warrior and took part in a number of major battles at the behest of Ali. Ali Ibn Abi Talib, was the Islamic Prophet Muhammad’s relative and viewed by Shia as the Prophet’s successor and the first Imam.

The organization also refers to its combatants as “Rijal Allah” or the “Men of God.” The utilization of the phrase sets the underpinning for a religiously focused message: These fighters are doing the work of God. This immediately casts their foes as agents of a notably less than holy origin. The term finds regular use as a descriptor for Lebanese Hizballah and Iraqi Shia Islamist fighters among the supporters and members from Iranian-backed proxy organizations currently fighting in Syria.

Nevertheless, it is still essential to acknowledge that despite the organization’s clear Shia-centric messaging, it has attempted to argue that it is not a sectarian entity. In Saraya al-Ashtar’s July “Statement No.4”, the group accused the government of “igniting sectarian strife between the communities.” SaA also claimed that, “all of [Saraya al-Ashtar’s] operations are directed at the pillars of the corrupt regime and its mercenaries.”

There are a few ways to measure such a statement. When compared to the bulk of Iranian-backed Shia Islamist group rhetoric, those organizations also claim to be non-sectarian while simultaneously promoting an undercurrent of heavy Shia-centric sectarian messaging. There is also the possibility the group is honestly conveying its “revolutionary” beliefs. Arguing that its enemy is not Sunni Muslims, just the government under the Khalifa royal family and their supporting elements, is given more weight considering the group has only directly targeted security personnel.

As with other Bahraini militant groups, Bahrain’s security personnel are regularly referred to as “mercenaries.” The charge that Bahraini security forces are “mercenaries” stems from Bahraini recruitment of outsiders, primarily Sunnis from Pakistan and other Arab states. Additionally, while the organization has not specifically called-out Saudi Arabia or other Gulf states which sent forces to Bahrain in 2011, it does make passing references to their presence as, “the occupation.” In an effort to demonstrate the weakness of the Khalifa royal family, the SaA regularly refers to the Bahraini royals as a “collapsing regime”.

Saraya al-Ashtar’s Messaging & Links to Iran

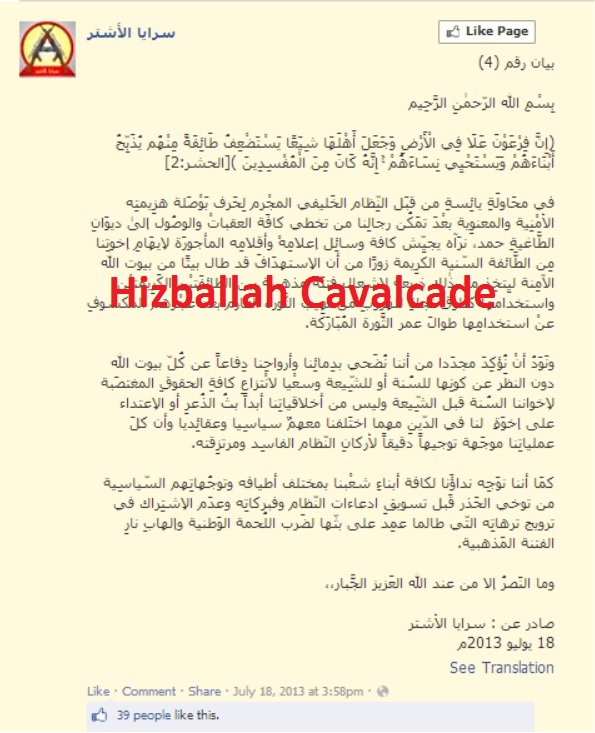

Figure 6: Saraya al-Ashtar’s Statement No. 4.

At the time this post was written the group had released nine statements dealing primarily with their militant activity. Besides claiming responsibility for bomb attacks, another main focal point for SaA’s releases have dealt with the fate of political prisoners and to show support for main figures involved with the protests The condition of Abdulwahab Husayn Ali Ahmed Isma’il (A.K.A. Abdulwahab Husayn), a major ideologue, politician, and protest leader since the uprisings in Bahrain in the 1990s, was a core concern in SaA’s 2nd (May 17, 2013) and 8th (November 10, 2013) released statements. At the start of the 2011 Bahrain protests, Husayn was arrested by Bahraini authorities,