Nestled into the ISIS Reader: Milestone Texts of the Islamic State Movement is a brief mention of a Tunisian that went by kunya Abu Usamah al-Tunisi. Based on primary source research for my own book, Your Sons Are At Your Service: Tunisia’s Missionaries of Jihad, Abu Usamah came to Iraq at the latest in early 2004 and fought in the Battles of Fallujah where his close relationship with both Abu Mus’ab al-Zarqawi and Abu Hamzah al-Muhajir led to his rise in the organization: first as the military leader of Baghdad’s southern belt and later as the leader of Majlis Shura al-Mujahidin (MSM)/the Islamic State of Iraq’s (ISI) entire foreign fighter operation. His closeness to al-Zarqawi and al-Muhajir might also help explain why Abu Usamah appeared as one of the masked individuals in the video that showed the beheading of the American Nicholas Berg in May 2004. More importantly, the fact that Tunisians held high-level positions, especially ones related to foreign fighting, helps explain why so many Tunisians would later become connected to these networks that helped recruit people to fight in Iraq, Libya, and Syria after 2011. Abu Usamah would eventually be killed in a U.S. airstrike in the city of Musayyib, in Babil Province, on September 25, 2007, along with a number of other senior ISI leaders.

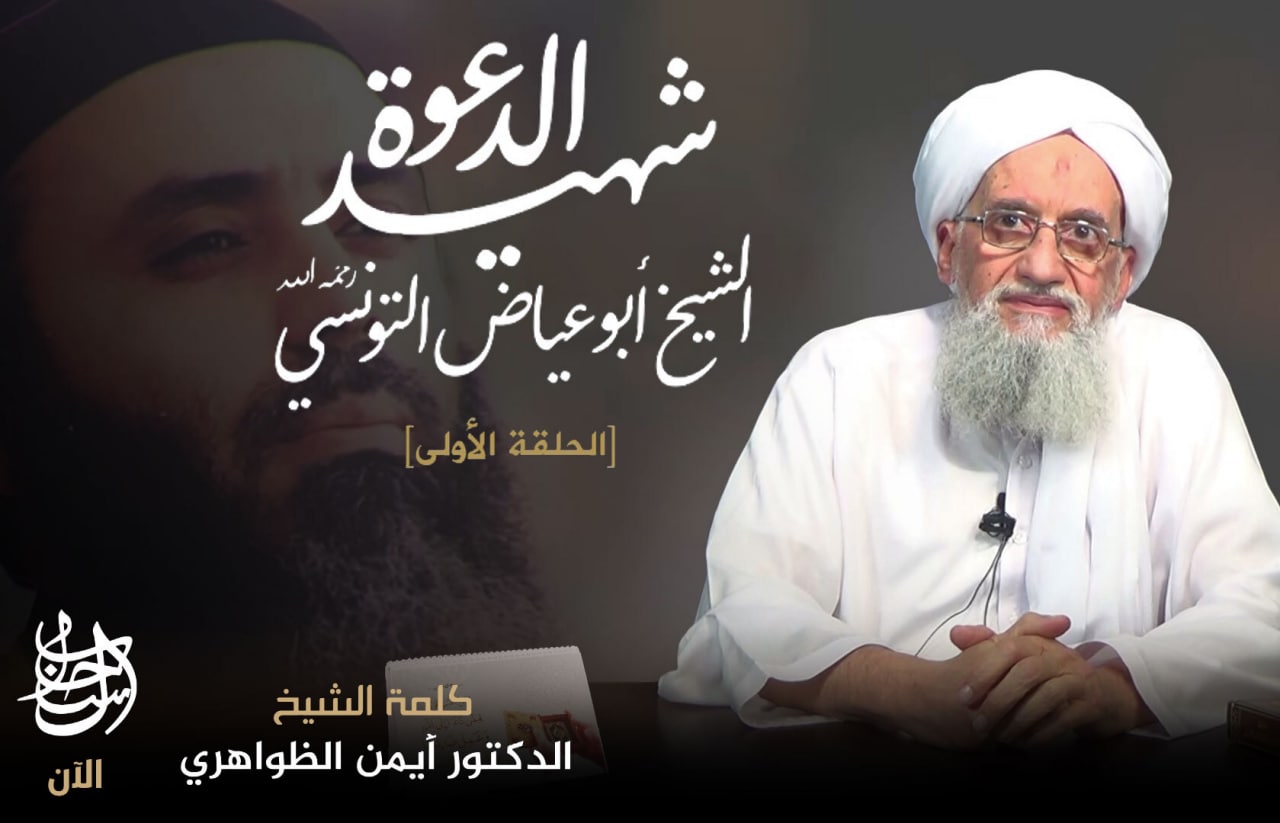

Although many Tunisians partook in jihadism prior to the Iraq war, the war inspired a new generation and cadre of individuals. For example, Hasan al-Brik, who would become Ansar al-Sharia in Tunisia’s (AST) head of dawa after the 2011 Tunisian revolution, traveled to Iraq in 2003. Like many others, he did not actually make it into Iraq, but rather took charge of a safe house in Syria where individuals were vetted before travelling to Iraq. For the Tunisians who survived, many, including al-Brik, would be arrested in Syria (and elsewhere) and rendered back to Tunisia to be placed into its prison system. Tunisia’s prisons in the seven to eight years before the revolution would be crucial for bringing together the first generation of Tunisian jihadis associated with Afghanistan and Europe-based networks and the second generation more associated with Iraq and the GSPC/AQIM networks. This prison exchange between the first and second generations of Tunisian jihadis would provide AST’s base for activities after the 2011 revolution and later the foreign fighter mobilization to Iraq, Libya, and Syria to either join Ansar al-Sharia in Libya, Jabhat al-Nusrah, or the Islamic State.

My book provides a lot of details on the Tunisians that joined the Iraq jihad, around 5,000 words in all. Due to that length and the focus of the ISIS Reader on primary sources, this post will highlight some details based strictly on research derived on this network from primary sources. However, if you want the entire picture, chapter four of my book gets into the entire history and story in full.

Click here to read the rest of this post.