Video:

English translation:

___________

Source: Telegram

To inquire about a translation for this video message for a fee email: [email protected]

Video:

English translation:

___________

Source: Telegram

To inquire about a translation for this video message for a fee email: [email protected]

Abstract: Fifteen years ago this month, a Tunisian operative named Nizar Nawar detonated a truck bomb outside the el-Ghriba synagogue in Djerba, Tunisia, killing 19, including 16 German and French tourists. Orchestrated by Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, it was al-Qa`ida’s first successful international attack after 9/11, but it has received far less attention than other attacks launched by the group. Court documents, case files, and primary sources shed significant new light on the attack and al-Qa`ida’s then modus operandi for international attack planning, which has both similarities and differences with recent international terrorist plots carried out by the Islamic State. In retrospect, the Djerba attack should have been a warning sign of the international threat posed by Tunisian foreign fighters, who are now one of the most dangerous cohorts within the Islamic State.

On April 11, 2002, a Tunisian al-Qa`ida operative named Nizar Bin Muhammad Nasar Nawar (Sayf al-Din al-Tunisi) ignored security officers’ orders to stop and drove a truck filled with liquid propane into the wall of el-Ghriba Synagogue, one of Africa’s oldest Jewish synagogues, in Djerba, Tunisia.1 Masterminded by Khalid Sheikh Mohammed (KSM),a the attack killed 14 Germans, three Tunisians, and two Frenchmen and left 30 others injured. Although it was al-Qa`ida’s first successful external operation following the 9/11 attacks, little has been written about how the attack materialized. It is one of the only large-scale, post-9/11 attacks or plots that has not been given a full retrospective treatment based on information that has been gleaned since its execution.2 Additionally, in light of the current Islamic State external operation campaign, it is worth examining how the Djerba bombing compares to more recent terrorist attacks in order to shed light on the evolution of terrorist attack planning.

This article draws on court documents, media reports, Guantanamo Bay prisoner review files, and Arabic primary sources from the jihadi movement to tell the story of the attack. While there is much contradictory information, the author has attempted to piece together what really happened by cross-referencing sources and weighing their credibility. While many scholars and general observers were surprised at the number of Tunisians who became involved with jihadism following the country’s revolution, this study of the network behind the Djerba attack makes clear that Tunisians have, in fact, played a significant role in the global jihadi movement for decades. Equally relevant to understanding the contemporary threat picture, this article sheds light on the longstanding importance of entrepreneurial individuals who link different nodes of networks together.3

Click here to read the article in full.

Abstract: Fifteen years ago this month, a Tunisian operative named Nizar Nawar detonated a truck bomb outside the el-Ghriba synagogue in Djerba, Tunisia, killing 19, including 16 German and French tourists. Orchestrated by Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, it was al-Qa`ida’s first successful international attack after 9/11, but it has received far less attention than other attacks launched by the group. Court documents, case files, and primary sources shed significant new light on the attack and al-Qa`ida’s then modus operandi for international attack planning, which has both similarities and differences with recent international terrorist plots carried out by the Islamic State. In retrospect, the Djerba attack should have been a warning sign of the international threat posed by Tunisian foreign fighters, who are now one of the most dangerous cohorts within the Islamic State.

On April 11, 2002, a Tunisian al-Qa`ida operative named Nizar Bin Muhammad Nasar Nawar (Sayf al-Din al-Tunisi) ignored security officers’ orders to stop and drove a truck filled with liquid propane into the wall of el-Ghriba Synagogue, one of Africa’s oldest Jewish synagogues, in Djerba, Tunisia.1 Masterminded by Khalid Sheikh Mohammed (KSM),a the attack killed 14 Germans, three Tunisians, and two Frenchmen and left 30 others injured. Although it was al-Qa`ida’s first successful external operation following the 9/11 attacks, little has been written about how the attack materialized. It is one of the only large-scale, post-9/11 attacks or plots that has not been given a full retrospective treatment based on information that has been gleaned since its execution.2 Additionally, in light of the current Islamic State external operation campaign, it is worth examining how the Djerba bombing compares to more recent terrorist attacks in order to shed light on the evolution of terrorist attack planning.

This article draws on court documents, media reports, Guantanamo Bay prisoner review files, and Arabic primary sources from the jihadi movement to tell the story of the attack. While there is much contradictory information, the author has attempted to piece together what really happened by cross-referencing sources and weighing their credibility. While many scholars and general observers were surprised at the number of Tunisians who became involved with jihadism following the country’s revolution, this study of the network behind the Djerba attack makes clear that Tunisians have, in fact, played a significant role in the global jihadi movement for decades. Equally relevant to understanding the contemporary threat picture, this article sheds light on the longstanding importance of entrepreneurial individuals who link different nodes of networks together.3

Click here to read the article in full.

_________________

As with all guest posts, the opinions expressed below are those of the guest author and they do not necessarily represent the views of this blogs administrator and does not at all represent his employer at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy.

Jihadology.net aims to not only provide primary sources for researchers and occasional analysis of them, but also to allow other young and upcoming students as well as established academics or policy wonks to contribute original analysis on issues related to jihadism. If you would like to contribute a piece, please email your idea/post to azelin [at] jihadology [dot] net.

Click here to see an archive of all guest posts.

—

Searching for the Shadowy Canadian Leader of ISIS in Bangladesh

By Amarnath Amarasingam

“You must be kidding, bro,” a friend of mine from Windsor, Ontario, tells me when I ask him about Tamim Chowdhury, the purported leader of ISIS in Bangladesh. “He was a quiet guy. Definitely religious. But a leader? I don’t think so.” He was not the first to express surprise when I asked around about Tamim. He did not seem to have made an impression on the people he met. Or so I thought.

The name Tamim Chowdhury first came on my radar in early 2015 when I was doing interviews with friends of another Windsor jihadi who had gone off to fight in Syria: Ahmad Waseem, known as Abu Turab, who was killed in March 2015 in Tal Hamis. Tamim’s name was floating around as someone who may have also left for Syria. I jotted down his name, but then became busy with other things.

Some months later, I spoke to another friend of Waseem’s and remembered to also ask about Tamim. He seemed a little surprised, and remarked that Tamim, facing harassment from law enforcement in Canada, had decided to simply move back to his home country of Bangladesh. Nothing to worry about, he said. I was skeptical.

The next time I saw his name appear, it became clear that Tamim was indeed important. A colleague of mine, who asked to be anonymous, pointed me to the ISIS Study Group website (which as of this writing has gone offline) where Tamim was mentioned as one of the leaders of ISIS in Bangladesh. A few months later, Zayadul Ahsan published an article in The Daily Star further cementing this theory. I started asking questions again, trying to find more people who may have known him in Windsor, and asking several jihadi fighters that I was in contact with in Syria. One of these fighters would provide a clue.

Connecting the Dots

One of the most famous blogs amongst journalists and analysts of Canadian foreign fighters is called “Beneath Which Rivers Flow.” It was an important blog, because it contained biographical details of two jihadis who had left from Calgary, Alberta, to fight, and eventually die, in Syria: Damian Clairmont and Salman Ashrafi. The most recent post was a letter to the mother of Damian, Christianne Boudreau, arguing that she should be proud of his sacrifice and proud to be the mother of a martyr. All the posts about Damian are signed by an individual calling himself “Abu Dujana al-Muhajir”. According to some individuals I interviewed, this blog was “owned” by Ahmad Waseem, but he allowed friends of his to post on it from time to time.

In a casual conversation about who this “Abu Dujana” might be with a Canadian fighter in Syria, he remarked: “I don’t know his real name, but he is of Bangladesh background and was from the 519 [area code for Windsor] area.” It seemed pretty clear that he was talking about Tamim Chowdhury. I realized that I was perhaps looking for Chowdhury in all the wrong places. He was certainly from Windsor and was friends with Ahmed Waseem. But Waseem had spent at least two years in Calgary, and returned home to Windsor, before leaving for Syria.

I had seen no evidence at the time that Tamim ever went to Calgary. But, if Tamim was Abu Dujana, the individual who wrote glowing eulogies of Calgary jihadi fighters, then he had to have spent time there. If this was true, our notion of the “Calgary cluster” of fighters just got more interesting.

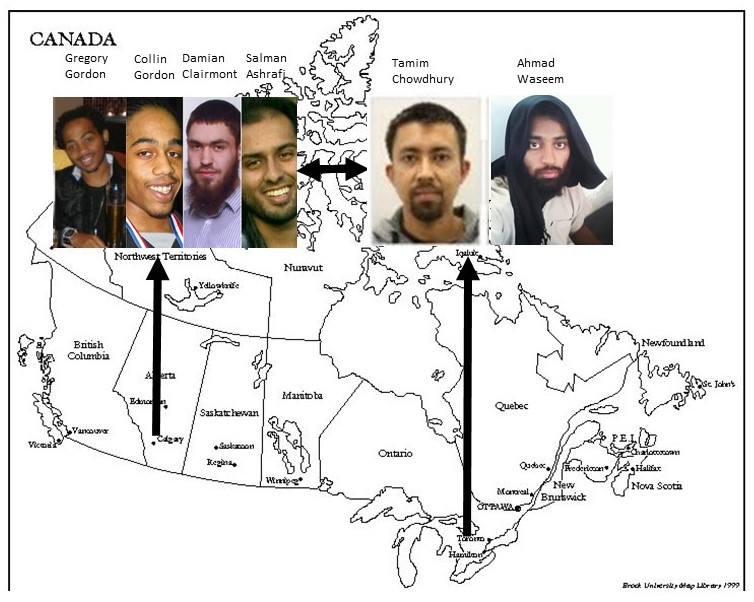

As I wrote in Jihadology last year, one of the first clusters that the Canadian public became aware of was in Calgary. The Calgary cluster consisted of Damian Clairmont, Salman Ashrafi, Gregory and Collin Gordon, Farah Shirdon, and a few others. While they were friends, their biographical details are quite varied. Ashrafi was born Muslim, educated at the University of Lethbridge, held a prestigious job at Talisman Energy, and was married with a child at the time of his departure in November or December 2012. In November 2013, he engaged in a suicide attack in Iraq that would kill him and 40 others.

Clairmont, on the other hand, was a white convert, suffered from bipolar disorder, was a high school dropout, and was homeless for a time in Calgary. Clairmont and Ashrafi were close friends and part of a study circle, at the 8th and 8th musallah, a storefront Islamic centre in downtown Calgary, with the Gordon brothers and several others. The Gordon brothers are featured prominently in Dabiq 15.

In interviews with their friends in Calgary, it initially seemed evident that Clairmont was the dominant personality, and influenced many of the other young men. Clairmont would leave Calgary in late 2012 as well. He fought with the Al-Qaeda affiliated Jabhat Al-Nusra, and was captured and killed by the Free Syrian Army in January 2014.

However, this image of the Calgary cluster is starting to change.

What We Know So Far

As I searched for more information on Tamim, on the night of 1 July 2016, five militants stormed the Holey Artisan Bakery, took hostages, and eventually hacked 24 people to death. If Tamim was the head of ISIS in Bangladesh, he was clearly behind this attack. Indeed, Bangladeshi police admitted in late July that Tamim was the mastermind. The fact that a Canadian was orchestrating attacks in Bangladesh has likely also led to some intelligence sharing between the two countries.

Once the trail led to Calgary, I started reaching out to friends there for more information about Tamim. The Bangladeshi media had produced two photos of Tamim (here and here), which I promptly sent to them. They confirmed that it was the same Tamim they remembered seeing in Calgary. Then things got interesting, and several details started falling into place.

This is what we know about Tamim Ahmed Chowdhury so far, even though several of these details still need to be made more precise:

He was born on July 25, 1986.

It is not clear yet if he was born in Canada or Bangladesh (probably the latter), but he is indeed a Canadian citizen.

He likely attended J.L. Forster Secondary School in Windsor. He competed for the school in a variety of track and field activities in 2004.

He graduated from the University of Windsor in Spring 2011, with an Honors in Chemistry, but probably majored/minored in other fields as well.

Some time after graduating from Windsor, he traveled to Calgary. It is unclear whether he moved to Calgary, or simply traveled back and forth several times. The latter seems more likely since those I spoke with in Calgary only remember him intermittently. He seems to have stayed low-key perhaps, and did not mix too closely with the Muslim community there.

One source says he remembers Tamim hanging out with Damian Clairmont at the 8th and 8th musallah, where Damian, Salman Ashrafi, Collin and Gregory Gordon, another individual named Waseem (last name unknown, but not Ahmad Waseem), and a few others held a private study circle. According to friends of theirs, Damian was likely the one who took a leadership role over the group, but it could be that Tamim was equally influential.

The same source says that Tamim almost certainly went to Syria, either directly from Calgary or from Windsor, “probably” in late 2012. Another source claims he saw Tamim hanging around the University of Calgary in 2013. This is further complicated by the fact that religious leaders in Windsor say they asked Tamim not to engage with youth at the mosques, clearly worried that he was potentially radicalizing them. This was possibly some time in 2013 as well. As such, details on when exactly he traveled to Syria are still murky.

From Syria, Tamim likely found his way to Bangladesh, perhaps even on direct orders from ISIS leadership. However, it is not clear when he landed in Bangladesh. One could venture an educated guess that the speed at which he took over ISIS in Bangladesh necessitated that he had some kind of “evidence” from ISIS central to “show” potential recruits.

Dabiq 14 features an interview with the “Amir of the Khilafah’s Soldiers in Bengal,” named as Shaykh Abu Ibrahim al-Hanif. Nowhere in the interview is there mention of Canada, Calgary, Windsor, or Tamim, but, again, one could venture an educated guess that it is the same person.

As of this writing, there are reports that Tamim may have crossed into India. On August 2, the Bangladeshi government put a 20 lakh ($25,000USD) bounty on his head.

Watch this space, and Twitter (@AmarAmarasingam) for updates on this story.

Amarnath Amarasingam is a Fellow at The George Washington University’s Program on Extremism, and co-directs a study of western foreign fighters at the University of Waterloo in Ontario, Canada.

A Canadian national, Colin Rutherford, who was detained by the Mujahideen of Islamic Emirate some 5 years earlier in the province of Ghazni was freed on Monday 11/01/2016 on grounds of humanitarian sympathy and sublime Islamic ethics with the intermediation by the Islamic country of Qatar and in accordance with the instructions of the leader of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan.

Spokesman of Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan

02/04/1437 Hijri Lunar

22/10/1394 Hijri Solar 12/01/2016 Gregorian

_____________________

The Clear Banner sub-blog on Jihadology.net is primarily focused on Sunni foreign fighting. It does not have to just be related to the phenomenon in Syria. It can also cover any location that contains Sunni foreign fighters. If you are interested in writing on this subject please email me at azelin [at] jihadology [dot] net.

—

Canadian Foreign Fighters in Syria: An Overview

By Amarnath Amarasingam

Public Safety Canada noted, in its 2014 terrorist threat assessment as well as later public statements, that the Canadian government was aware of at least 130-145 individuals “with Canadian connections who were abroad and who were suspected of terrorism-related activities” [1]. The Syrian conflict, as well as the more recent establishment of the “caliphate” by the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), has captured the imagination of some Muslim youth from around the world, who now migrate into Syria and Iraq to wage jihad. According to the 2014 threat report, there are at least 30-40 Canadians who are currently fighting in Syria/Iraq [2], but based on interviews with community members in Canada, I would place the number closer to sixty.

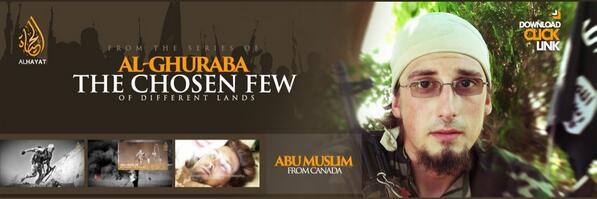

While the number of Canadians traveling to Syria has been relatively low, compared to other Western countries like the United Kingdom or Belgium, Canadian fighters have been quite prominently featured by the English-language Al Hayat Media Centre of the Islamic State. Andre Poulin, from Timmins, Ontario, was the first Canadian to appear in Islamic State propaganda materials [3]. The slickly produced video, using stock footage of ski slopes and skyscrapers, runs for eleven minutes and shows Poulin (known as ‘Abu Muslim’) speaking directly to the camera. “Before Islam I was like any other regular Canadian,” he says. “I watched hockey. I went to the cottage in the summertime. I loved to fish.” As the video depicts, Poulin died in August 2013 during an attack on Mennegh Military Airport in Aleppo.

Another Canadian featured in early 2014 is Farah Shirdon from Calgary, Alberta. Shirdon, known as Abu Usamah, can be seen burning his Canadian passport and threatening Western powers [4]. Shirdon, who for a time was thought to have been killed, achieved greater fame when he conducted a Skype interview with Vice News in September 2014 [5]. The most recent Canadian to appear in an Islamic State recruitment video is John Maguire from Ottawa. Standing amidst rubble, Maguire, much like Poulin, implores Muslims in the West to make hijrah, or emigrate, to the Islamic State [6]. In the interim period between the Poulin and Maguire videos, the Canadian government joined the coalition of countries seeking to militarily dismantle the Islamic State. Accordingly, Maguire’s video is more confrontational, lambasting the Canadian government for its military aggression, and arguing that the attacks in Ottawa and Montreal in October 2014 should be seen as a natural consequence.

The Canadian Clusters

Since early 2014, I have been tracking and attempting to build a database of Canadian fighters in Syria and Iraq. In discussions with community members, friends and families, and journalists, we have confirmed the identities (albeit unevenly and incompletely) of around 35-40 Canadians who have traveled to Syria and Iraq. Of these Canadians, at least 5-7 individuals are women and 5-7 are converts to Islam. At the time of writing, at least 12 Canadians have died in the fighting – 7 from Alberta, 4 from Ontario, and 1 from Quebec. The vast majority of fighters are first or second generation youth who were born Muslim into a variety of South Asian and Middle Eastern backgrounds. As many scholars have noted, there is no one single profile of these individuals – their ethnic, cultural, economic and religious backgrounds are varied and diverse. What does seem to be a common characteristic of almost all Canadian foreign fighters is the role played by group dynamics and friendship networks in influencing their decision to fight abroad [7].

One of the first clusters that the Canadian public became aware of was in Calgary, Alberta. The Calgary cluster consisted of Damian Clairmont, Salman Ashrafi, Gregory and Collin Gordon, Farah Shirdon, as well as a few other individuals who have yet to be identified [8]. While they were friends, their biographical details are quite varied. Ashrafi was born Muslim, educated at the University of Lethbridge, held a prestigious job at Talisman Energy, and was married with a child at the time of his departure in November or December 2012. In November 2013, he engaged in a suicide attack in Iraq that would kill him and 40 others [9].

Clairmont, on the other hand, was a white convert, suffered from bipolar disorder, was a high school dropout, and was homeless for a time in Calgary. Clairmont and Ashrafi were close friends and part of a study circle with the Gordon brothers and several others. In interviews with their friends in Calgary, it is evident that Clairmont was the dominant personality, and influenced many of the other young men. Clairmont would leave Calgary in late 2012. He fought with the Al-Qaeda affiliated Jabhat Al-Nusra, and was captured and killed by the Free Syrian Army in January 2014 [10].

Another fighter with some connection to the Calgary study circle is Ahmed Waseem from Windsor, Ontario. Waseem’s story is particularly interesting because he came back to Canada after an injury sometime in 2013 [11]. After experiencing increased surveillance and having his passport seized by Canadian intelligence agents, he secured a fraudulent passport and has, according to his Twitter feed (now suspended), been regularly involved in fierce battles in Syria ever since.

While it was the Calgary cluster that initially made the news in Canada, Ontario is still home to a far greater number of foreign fighters than Alberta. Of the Canadian foreign fighters in Syria and Iraq, close to half are from Ontario. Perhaps the most intriguing case is the story of Andre Poulin from Timmins. Born in 1989, Poulin converted from Roman Catholicism sometime in 2009, noting in an online forum that he was “convinced through the scientific nature of the Qur’an that it was indeed the truth.” Poulin traveled to Syria in November or December 2012.

In the early stages of researching Poulin’s story, he did not seem to be part of any “cluster” – indeed, there are only a handful of Muslims in Timmins, a small city of 43,000 people with no mosque. Around 2011, Poulin told family and friends that he was moving to Toronto to be closer to Muslims. In Toronto, Poulin met with Muhammad Ali from Mississauga [12]. They had become friends in an online forum long before this first meeting. Once Poulin was in Toronto, they would see each other regularly. Ali was born in 1990 and went to Ryerson University to study aerospace engineering. He did not do well in school, however, and was kicked out a year later. It was then that he started asking questions about life and the afterlife, and found many of the answers in Islam, the religion of his upbringing. He went to online forums and began interacting with fellow Muslims – one of them being Poulin. Ali would leave for Syria in April 2014, several months after Poulin had died.

Poulin made other friends as well, and seems to have influenced them towards his way of thinking. At least four others from Toronto – Tabirul Islam, Abdul Malik, Noor, and Adib – became friends with Poulin and left for Syria around the same time he did. However, very little is known about them currently, except that some or all of them returned to Toronto in Feb 2013 – only to leave again in July 2014. Interestingly, on 13 July 2014, Muhammad Ali posted a screenshot of a text-message conversation he was having on his phone. The message read: “This is the friends of Omar Abu Muslim from Canada. We are in Turkey now and we want to know which way to get into Syria and join Islamic State.” From this message we can deduce that while Ali and Poulin were friends in Toronto, Ali likely did not know Poulin’s other Toronto friends until later. In discussions with some members of the Islamic State over social media, it seems likely that these four Canadians may currently be fighting in Iraq.

Despite these significant gaps we know quite a bit about the Calgary and Toronto clusters. As of this writing, community sources in Edmonton also confirmed that three Somali Canadians – brothers Hamsa and Hirsi Kariye and their cousin Mahad Hersi – had died fighting in Syria, and as many as ten may have departed from the city in 2014. In early March 2015, it was also reported that six individuals from Quebec (the Laval and Montreal areas) – Bilel Zouaidia, Shayma Senouci, Mohamed Rifaat, Imad Eddine Rafai, Ouardia Kadem, and Yahia Alaoui Ismaili – had departed to the Islamic State. There are also discussions in various communities across the country of possible clusters in a variety of major cities across Canada. At the moment, however, very little is known about them.

Conclusion: Foreign Conflicts, Local Implications

The involvement of Canadians in foreign conflicts has always been a cause for concern. There are fears that Canadians may contribute, either financially or otherwise, to violent social movements abroad. There are related fears that these individuals may arrive back in Canada to radicalize others or to launch attacks on the homeland. As the 2014 threat assessment noted, “The Government is aware of about 80 individuals who have returned to Canada after travel abroad for a variety of suspected terrorism-related purposes. Those purposes varied widely.

Some may have engaged in paramilitary activities. Others may have studied in extremist schools, raised money or otherwise supported terrorist groups” [13].

It

__________

Statement:

A few months earlier, Mujahideen of Islamic Emirate captured a Canadian national, a resident of Toronto city and an agent of this country’s spy agency (Colin McKenzie Rutherford) in Ghazni province.

The mentioned person came under Mujahideen surveillance before his capture because of his suspicious actions. The documents

seized and investigations carried out after his arrest showed that he had entered the country while working for a spy agency and had been working as an active spy for a long time, gathering intelligence information about Mujahideen.

Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, through an earlier released statement asked the Canadian government to accept the terms laid out by Islamic Emirate in order to solve this case and once again re-iterates itself to the Canadian government to take urgent steps to solve this case or this detainee could face a trial. The video of the detainee has been released as promised by Islamic Emirate, which can be viewed at the following link.

Video:

_____