NOTE: As with all guest posts, the opinions expressed below are those of the guest author and they do not necessarily represent the views of this blogs administrator and does not at all represent his employer at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy.

Jihadology.net aims to not only provide primary sources for researchers and occasional analysis of them, but also to allow other young and upcoming students as well as established academics or policy wonks to contribute original analysis on issues related to jihadism. If you would like to contribute a piece, please email your idea/post to azelin [at] jihadology [dot] net.

Click here to see an archive of all guest posts.

—

ISIS and the Hollywood Visual Style

By Cori E. Dauber and Mark Robinson

The slick production techniques ISIS uses in its propaganda are the reason people have written about their videos as “Hollywood quality” or “like Hollywood movies.” Obviously this is not, strictly speaking, true. When people write about ISIS videos being like “Hollywood action films,” they don’t mean that in a literal sense – Hollywood blockbusters, after all, cost on average several hundreds of millions of dollars to produce. But that doesn’t mean people saying that aren’t onto something. They’re seeing something in ISIS videos that is reminiscent of Hollywood films that they don’t see in the videos of other groups. Yes, ISIS videos are of far higher quality than are those of other groups – we would say they are, technically, a generation ahead of most others. But there’s something else going on here that people are cueing on. We would argue that, visually, ISIS videos mimic what could be called a “Hollywood visual style.” And this is being done so systematically and carefully that, while its entirely possible that it’s accidental, we find that very unlikely.

While there has been a great deal of work done on the way ISIS uses Social Media to distribute their materials, our focus is on the content of their output, specifically, on their visual material. We believe this focus is important for a number of reasons, not the least of which is the enormous amount of empirical research that argues that visual material, in many contexts, can actually be more powerful than textual. That is to say, the image can trump the word: it more effectively draws the viewer’s attention, it is remembered more accurately and for a longer period of time.

That’s all well and good, but what specifically does it mean to say that ISIS material is sophisticated in visual terms, or that their videos are done in a “Hollywood visual style?” While that’s a complicated question to get after, one can start by breaking it down in terms of the way ISIS makes use of some of the compositional elements of production to contribute to the persuasive power of their materials, in a way that other groups either cannot or simply do not. We’ll directly contrast some of their videos with some of Jabhat al Nusrah’s to make the point.

- What the viewer will notice first: the opening graphics package and the clarity of the image.

ISIS employs “industry standards” for video. That doesn’t necessarily mean standard for Hollywood, it might mean what you see in commercial video or advertisement, but its what we have become accustomed to seeing, what the eye has become accustomed to for anyone who watches a good bit of professionally shot and uploaded media. Neither of us can speak to what is standard outside of Europe and North America, but it seems worth noting that ISIS is systematically working to use visual standards that will give their videos an underlying professional look to someone whose eye is accustomed to a European or North American industry standard.

This is done through a variety of techniques: for example, through the way they deal with the colors in their videos, by adjusting the range of colors you see. They minimize the color palette that comes across on video so that, for instance, there are fewer variances, fewer “shades of red,” presented in their videos than there were in the physical world seen through the viewfinder when they were filming. The result is that the reds they do show you are more vibrant, brighter, higher contrast, and they come across looking sharper and clearer. Just look at how saturated the colors of the produce are in this frame from one of the Mujatweets Episodes:

This requires planning, both pre-and post-production. Many of their videos were clearly shot by a media team trained (and trained sufficiently) to execute in a “digital age” style. So you see this kind of color saturation, high contrast, and an emphasis on resolution. You also see a shallow depth of field – in other words, there is a tight focus on something or someone, but the rest of the visual field is intentionally out of focus. That’s a good example of what we mean by “Hollywood style.” It points specifically to a contemporary trend set by younger media professionals, but someone who had just randomly picked up a camera certainly wouldn’t know to do that. If you look at the most expensively produced Hollywood films of the 1970s or ‘80s, you won’t see a shallow depth of field, because it’s a fairly recent development. As an example:

When video is shot (and when someone prepares to share it via the web or phone) the video must go through a compression process. This makes the files smaller at the cost of lost resolution and visual impact. Most videos we look at are grainy in part because of this process. Another reason ISIS’ videos read as so crisp and clear relative to those of other groups is that they have been shot more carefully and compressed much more carefully.

In less professional videos, already compressed sequences are put together, then exported through a compressor. These lesser quality videos are thus compressed to a point that they appear amateurish, since they read as if the person who produced them didn’t know or, at least, didn’t care that the resolution drops significantly when videos are prepared this way. This is what creates the grainy, pixelated effect. Think about how you automatically can tell the difference between the professionally shot and prepared footage from a news network and the amateur footage that network pulled from some random guy who just happened to be there with a cellphone camera in his pocket when a newsworthy event took place.

IS videos that are crystal clear suggest that there was a crafting hand behind them, one that was trained and careful.

Earlier videos from AQ and the affiliates paid no attention to contemporary industry principles and standards. More recent videos from ISIS (and more and more from some other groups) mark a clear movement: they are being produced according to knowledge and execution of industry standard in the entire process, from pre- to post-production. It seems clear that their media teams are getting trained somewhere.

There is no question that the content of some of the most recent videos released by JN were substantially better than what had been their baseline. But as often seems to be the case with groups other than ISIS, these major advances do not then override, with the prior, weaker style disappearing. There is not a single, controlling visual style, so that even after videos of much higher quality are released, those videos will then be followed by others that look the same as earlier, weaker releases did.

In this JN video that was released recently, they didn’t really know what they were doing, so they were filming with a non-professional, handy-cam, while moving way too fast:

If we just take a still of the sign you can see why that footage appears to be of low quality. Look at the leaves around the sign, and you can see that the image is actually pixelating.

![]()

As far as graphics are concerned, as software became available making it easier and easier to produce computer-animated graphics, not only did it become commonplace for these videos to begin with animations, they are often now relatively sophisticated even if the accompanying video is of very low quality. Still, ISIS is in a class by themselves here for several reasons: the consistency of the quality, the crisp resolution of almost all of the graphics they use, and, a key factor, the design. Many groups acquired the ability to incorporate animations, but not necessarily any ability to design ones that worked. Often they go on forever, they’re distracting, they’ve got so much going on, the eye can’t figure out where to focus, and so on.

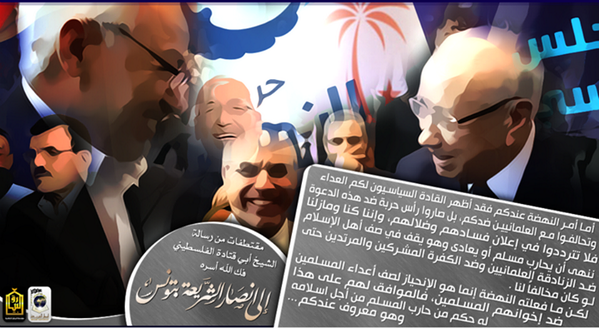

On this measure, JN made enormous leaps forward recently:

It isn’t, by the way, only JN making these leaps. This one from AQAP is hard to miss: its eye-catching, attractive, and likely took several days of work by someone who really knew what they were doing:

But of course groups now insert graphics into the middle of videos, not just at the beginning.

And compare that to the way ISIS uses graphics in the Mujatweets series:

- Composition:

Most ISIS videos appear as if every frame of every shot of every scene has been carefully calculated, thought through, and laid out.

Just consider the stock piece of footage that they use over and over (and that some news networks use as a “visual metaphor” for ISIS): two rows of fighters, one in the black “ninja” outfit, the other row dressed in white, both marching in unison, shot in slow motion and from below. Keep in mind, it is a truism that what is filmed from below will appear larger, more imposing, more authoritative, and so forth. It’s stock footage for them because it came out so well.

Now consider the JN version by way of comparison. You hardly need a communication or media specialist to point out the differences – the outfits don’t match, the editing is jumpy, “professional” is hardly the word that leaps to mind here. But part of the reason it looks this