NOTE: As with all guest posts, the opinions expressed below are those of the guest author and they do not necessarily represent the views of this blogs administrator and does not at all represent his employer at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy.

Jihadology.net aims to not only provide primary sources for researchers and occasional analysis of them, but also to allow other young and upcoming students as well as established academics or policy wonks to contribute original analysis on issues related to jihadism. If you would like to contribute a piece, please email your idea/post to azelin [at] jihadology [dot] net.

Past Guest Posts:

Mark Youngman, “Book Review of David Malet’s “Foreign Fighters: Transnational Identity in Civil Conflicts”,” June 20, 2013.

Hazim Fouad, “Salafi-Jihadists and non-jihadist Salafists in Egypt – A case study about politics and methodology (manhaj),” April 30, 2013.

Daveed Gartenstein-Ross and Tara Vassefi, “Perceptions of the “Arab Spring” Within the Salafi-Jihadi Movement,” November 19, 2012.

Jack Roche, “The Indonesian Jamā’ah Islāmiyyah’s Constitution (PUPJI),” November 14, 2012.

Kévin Jackson, “The Pledge of Allegiance and its Implications,” July 27, 2012.

Behnam Said, “A Brief Look at the History and Power of Anasheed in Jihadist Culture,” May 31, 2012.

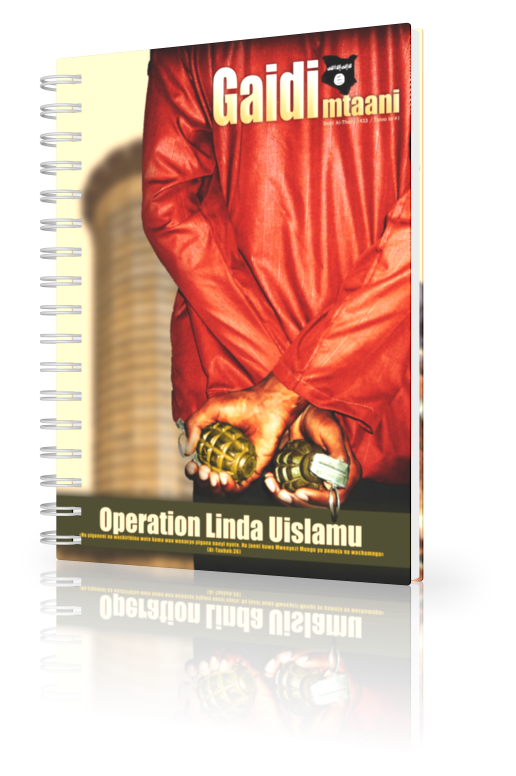

Jonah Ondieki and Jake Zenn, “Gaidi Mtaani,” April 24, 2012.

Joshua Foust, “Jihadi Ideology Is Not As Important As We Think,” January 25, 2011.

Charles Cameron, “Hitting the Blind-Spot- A Review of Jean-Pierre Filiu’s “Apocalypse in Islam,” January 24, 2011.

Daveed Gartenstein-Ross, “Why Jihadi Ideology Matters,” January 21, 2011.

Joshua Foust, “Some Inchoate Thoughts on Ideology,” January 19, 2011.

Marissa Allison, “Militants Seize Mecca: Juhaymān al ‘Utaybī and the Siege of the Grand Mosque in Mecca,” June 9, 2010.

—

Turkish Fighters in Syria, Online and Off

By North Caucasus Caucus

Click here for a PDF version of this post

NOTE:

This piece provides a granular look at the backgrounds of Turkish citizens fighting in Syria, building on a recent article by Soner Cagaptay and Aaron Y. Zelin on the challenges Turkey may face in the future emanating from jihadis operating near Turkey’s southern border and the eventual return home of Turkish jihadis. While I have spent a considerable amount of time living, working and studying in Turkey, I am by no means an expert on Turkish jihadi groups or jihadi movements in general. I am a researcher on the politics of the Caucasus, but while researching foreign fighters in Syria from the Caucasus, I continually noted their engagement with Turkish jihadi material and felt it was an issue that needed further exploration.

INTRODUCTION

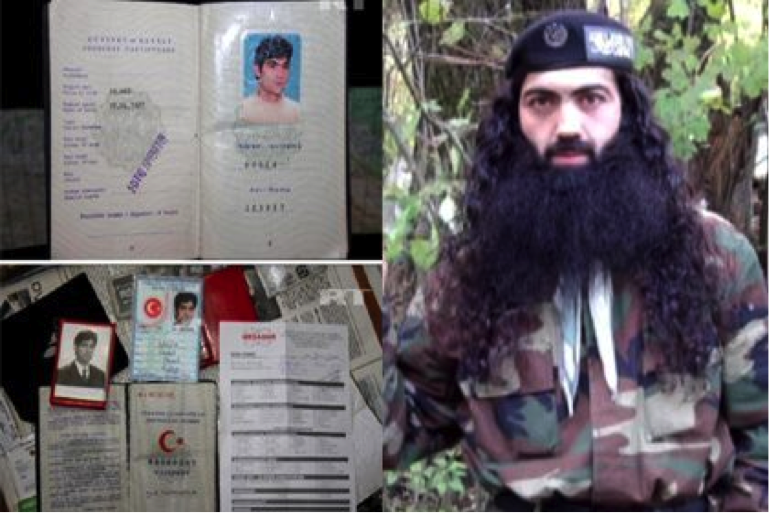

Over the last three decades, Turkish citizens have travelled to fight and die in conflicts both close and distant. Turkish citizens have fought in Iraq, Afghanistan (both against the Soviets and the United States), Bosnia, and the North Caucasus, sometimes occupying leadership positions in Islamist armed groups. For example, Cevdet Doger (aka Emir Abdulla Kurd) was second-in-command of foreign fighters in the North Caucasus before his death in May 2011.

Cevdet Doger and recovered Turkish identification tables, Source: sehidler.com

I will not venture to estimate how many Turkish citizens are fighting in Syria. In August 2012, Turkish journalist Adem Ozkose reported on the deaths of four Turkish fighters in Aleppo and said they were part of a group of 50 Turks fighting in that region. In the year since, it is conceivable that this number has grown along with Syria’s general population of foreign fighters.

SYRIA IN TURKISH ONLINE SPACES

There is a large amount of Turkish pro-jihadi material on Facebook relating to Syria. For example, the page, “Suriye İslam Devrimini Destekliyoruz,” (“We Support Syria’s Islamic Revolution”) has over 11,000 “Likes.” Al-Nusra Front (Nusret Cephesi in Turkish) and the Islamic State of Iraq and Sham (ISIS) both have Turkish language fan pages which are regularly shut down by Facebook but are always quickly reestablished. Turks interested in following jihadi activity in Syria are not wanting for online news coverage.

Just as Arabic-language material is translated and posted on Turkish-language sites, material from Turkish languages pages makes its way to Islamist users from other countries. For example, the pro-Islamist Turkish news website, Islah Haber, which regularly publishes news on Turkish fighter activity and deaths, uploaded an Arabic language video on 9 July 2013 that included several Turks speaking (with Arabic subtitles) about why they went to Syria. One fighter emphasized Assad’s killing of women and children and the hope of establishing a sharia-based state as a prime motivator.

The caption identifies him as “Abdullah Azzam the Turk, connected to Thughur Bilad al Sham,” Source: Islah Haber

YouTube videos are sometimes used in recruitment efforts. The Russian language website, fisyria.com, released a video on 03 July 2013 from Emir Seyfullah, an ethnic Chechen and then-spokesman of ISIS-affiliate Jaish al-Muhajirin wa Ansar. In the video, Emir Seyfullah speaks in heavily accented Turkish, calling for Turks to come help establish sharia in the land of Sham; his speech is intercut with footage of Syrian military jets on bombing runs. Jamestown’s Mairbek Vatchagaev wrote that Seyfullah is from the Pankisi Gorge region of Georgia. However, it is possible that he lived in Istanbul before the war in Syria. Many former fighters from the North Caucasus continue to live in Turkey. This has led to violence in the past, such as the September 2011 assassination of two former fighters, allegedly by Russian security services, in Istanbul’s Zeytinburnu neighborhood.

Screenshot of YouTube video about Turkish martyrs in Syria

The amount of material about Syria uploaded onto YouTube in all languages is nearly endless. However, one recent video provided insight into the extent of Turkish fighter involvement in Syria. On 05 July 2013, an account (now-deleted), associated with the Facebook page, “Suriye Devrimi Sehidleri,” (“Martyrs of the Syrian Revolution”) uploaded a video entitled, “Turkiyeli Sehidler” (Martyrs from Turkey). The video shows the images of 27 different alleged Turkish fighters killed in Syria.

Category: Guest Post

GUEST POST: Jabhat al-Nusra and the Islamic State of Iraq and ash-Sham: Raqqah Governorate

NOTE: As with all guest posts, the opinions expressed below are those of the guest author and they do not necessarily represent the views of this blogs administrator and does not at all represent his employer at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy.

Jihadology.net aims to not only provide primary sources for researchers and occasional analysis of them, but also to allow other young and upcoming students as well as established academics or policy wonks to contribute original analysis on issues related to jihadism. If you would like to contribute a piece, please email your idea/post to azelin [at] jihadology [dot] net.

Past Guest Posts:

Hazim Fouad, “Salafi-Jihadists and non-jihadist Salafists in Egypt – A case study about politics and methodology (manhaj),” April 30, 2013.

Daveed Gartenstein-Ross and Tara Vassefi, “Perceptions of the “Arab Spring” Within the Salafi-Jihadi Movement,” November 19, 2012.

Jack Roche, “The Indonesian Jamā’ah Islāmiyyah’s Constitution (PUPJI),” November 14, 2012.

Kévin Jackson, “The Pledge of Allegiance and its Implications,” July 27, 2012.

Behnam Said, “A Brief Look at the History and Power of Anasheed in Jihadist Culture,” May 31, 2012.

Jonah Ondieki and Jake Zenn, “Gaidi Mtaani,” April 24, 2012.

Joshua Foust, “Jihadi Ideology Is Not As Important As We Think,” January 25, 2011.

Charles Cameron, “Hitting the Blind-Spot- A Review of Jean-Pierre Filiu’s “Apocalypse in Islam,” January 24, 2011.

Daveed Gartenstein-Ross, “Why Jihadi Ideology Matters,” January 21, 2011.

Joshua Foust, “Some Inchoate Thoughts on Ideology,” January 19, 2011.

Marissa Allison, “Militants Seize Mecca: Juhaymān al ‘Utaybī and the Siege of the Grand Mosque in Mecca,” June 9, 2010.

–

By Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi

A couple of weeks ago I wrote on emerging signs of an apparent split in some respects between Jabhat al-Nusra (JAN) and the Islamic State of Iraq and ash-Sham (ISIS). What other evidence has emerged since then? Here I will just focus on the rebel-held city of Raqqah and the wider Raqqah Governorate.

For one thing, the nature of the channel ‘ash-Sham’, which has put out a number of videos purportedly showing members of ISIS, has now become clear. While its now-terminated Youtube profile gave the impression that ash-Sham is run by someone in the United States, the channel is actually based in the city of Raqqah.

Here is an advertisement board put out by ash-Sham in Raqqah, with the slogan ‘Together, let us spread our Shari’a.’ In effect, the channel is a media front for ISIS in Raqqah, and so ash-Sham’s Facebook page also uploaded a photo of the entrance to ISIS’s security office in Raqqah, together with a view of the interior of the office.

More generally, the presence of ISIS supporters can be observed in videos of rallies in Raqqah. For instance, in this video clip of a 24 May demonstration for Qusayr in Raqqah, an ISIS banner can be seen, though it should also be noted that some of the protestors are also waving JAN flags, alongside others who hold FSA flags and one demonstrator for Harakat Ahrar ash-Sham al-Islamiya (HASI), which was the main group of rebel battalions that took over Raqqah in March.

Here is another video clip of protests in Raqqah on that day, again featuring an ISIS banner alongside an ISIS flag, together with HASI and FSA banners. Note also this photo of one of the processions in solidarity with Qusayr with two ISIS flags in the background.

Further, on 31 May, a Friday protest was held in Sayf ad-Dawla street under the name of ‘Our Red Lines’ (alluding to the Obama administration’s shifting of the ‘red line’ on the use of chemical weapons in Syria). Here too one can observe an ISIS flag alongside FSA flags and white banners with the Shahada in black, signifying the realm of Islamic law.

Some inferences can be drawn here. First, whatever ideological differences the protestors and activists in Raqqah may have (and as I have noted before, there is a secular and anti-sectarian trend in the city), cooperation and accommodation rather than mutual hostility remain the norm at demonstrations, particularly those organized around common causes like solidarity with the rebels in Qusayr.

True, some activists in Raqqah have also protested against the rise in Shari’a courts, but to the extent that ISIS and other groups compete to win the support of locals, the competition for ‘hearts and minds’ is generally being pursued peacefully.

The second point to note is that the presence of JAN flags alongside ISIS symbols at demonstrations illustrates that posing an antagonistic JAN-ISIS dichotomy can be simplistic. Some of the activists aligned with ISIS and JAN may simply view each other’s names and banners as mere synonyms.

In a similar vein to JAN’s distribution of works by the likes of Abd al-Wahhab I have noted previously, ISIS is also offering study circles for the Qur’an and life of the Prophet at various mosques. Further, now that the presence in Raqqah has been established for some time, ISIS has taken upon itself to exercise jurisdiction over perceived criminals and regime agents.

The latter was shown with the widely-circulated execution video last month of three men accused of being officers in Assad’s forces, while an example of the former has recently come to light with ISIS’s arrest of a man identified as ‘Ahmad al-Assaf’, accused by ISIS of leading a gang responsible for stealing motorcycles and cars in Raqqah.

One further point suggesting continuity between ISIS and JAN in the Raqqah area and a relationship more or less along the lines of seeing the two there as synonymous is the issue of the northern border town of Tel Abyad. This town was the site of clashes between the northern Farouq Battalions and JAN at the end of March, most likely over control of border access points and resources.

Renewed clashes appear to have emerged in Tel Abyad at the end of May, only this time between Farouq (or the recently formed Liwaa Mustafa) and ISIS, with the latter then taking the initiative to distribute a notice with the ISIS insignia to residents on their right to report on and complain about misconduct by any of the mujahideen.

In short, the case of the city of Raqqah and the surrounding area is indicative of the complexity on the ground of the relationship between JAN and ISIS. In some places elsewhere in Syria, there is probably antagonism between those adopting the JAN label and others the ISIS symbols, but the picture in Raqqah and Raqqah governorate is one of continuity between ISIS and JAN.

Most importantly, the modus operandi of those identifying as ISIS- increasingly prevalent in Raqqah city rather than the banner of JAN- is not fundamentally different from JAN. Ultimately, it is ISIS’ actions on the ground that matter more than a name and flag.

Thus, I do not see a gradual shift to ISIS from JAN in the Raqqah area as having a significant impact for fighters and activists in sympathy with al-Qa’ida. Deeds- and not symbols or names- will decide their fortunes.

Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi is a Shillman-Ginsburg Fellow at the Middle East Forum and a student at Brasenose College, Oxford University. His website is https://www.aymennjawad.org. Follow on Twitter at @ajaltamimi

GUEST POST: Majlis Shura al-Mujahidin: Between Israel and Hamas

NOTE: As with all guest posts, the opinions expressed below are those of the guest author and they do not necessarily represent the views of this blogs administrator and does not at all represent his employer at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy.

Jihadology.net aims to not only provide primary sources for researchers and occasional analysis of them, but also to allow other young and upcoming students as well as established academics or policy wonks to contribute original analysis on issues related to jihadism. If you would like to contribute a piece, please email your idea/post to azelin [at] jihadology [dot] net.

Past Guest Posts:

Hazim Fouad, “Salafi-Jihadists and non-jihadist Salafists in Egypt – A case study about politics and methodology (manhaj),” April 30, 2013.

Daveed Gartenstein-Ross and Tara Vassefi, “Perceptions of the “Arab Spring” Within the Salafi-Jihadi Movement,” November 19, 2012.

Jack Roche, “The Indonesian Jamā’ah Islāmiyyah’s Constitution (PUPJI),” November 14, 2012.

Kévin Jackson, “The Pledge of Allegiance and its Implications,” July 27, 2012.

Behnam Said, “A Brief Look at the History and Power of Anasheed in Jihadist Culture,” May 31, 2012.

Jonah Ondieki and Jake Zenn, “Gaidi Mtaani,” April 24, 2012.

Joshua Foust, “Jihadi Ideology Is Not As Important As We Think,” January 25, 2011.

Charles Cameron, “Hitting the Blind-Spot- A Review of Jean-Pierre Filiu’s “Apocalypse in Islam,” January 24, 2011.

Daveed Gartenstein-Ross, “Why Jihadi Ideology Matters,” January 21, 2011.

Joshua Foust, “Some Inchoate Thoughts on Ideology,” January 19, 2011.

Marissa Allison, “Militants Seize Mecca: Juhaymān al ‘Utaybī and the Siege of the Grand Mosque in Mecca,” June 9, 2010.

—

By Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi

In recent weeks and months there has been a cacophony of Salafi protest that has swept Gaza against the ruling Hamas government related to treatment of prisoners, corruption, and ability to practice Islam as they see fit. One of the groups speaking out has been Majlis Shura al-Mujahidin fi Aknaf Bayt al-Maqdis, a jihadi organization that is sympathetic to al-Qaeda’s worldview. By glomming onto a mainstream Salafi cause, MSM is attempting to co-opt individuals to gain a stronger footing within Gaza to challenge Hamas (albeit only at the political and not military level yet), whom they view as an enemy similar, though, on a lesser level than Israel.

Background

Following a cross-border attack on Israel carried out by one Egyptian and one Saudi fighter, the organization’s formation was first declared on 19 June 2012, which was announced in a video released from the Sinai Peninsula, featuring seven fighters. The two attackers read their martyrdom wills in the video as well.

In the first part of the video, the speaker in the center reads out a statement and begins by invoking Qur’an 61:4, ‘Verily does God love those who fight in his path in a row as though they were a firm edifice,’ followed by references to standard global jihadist themes such as the necessity of implementing the Shari’a on Earth and reviving the glory of the Ummah.

The Majlis also appeals to fellow Muslims in countries like Lebanon, Jordan, as well as the ‘Syrian Muslim people- the mujahid [people] brutalized under the control of the idolatrous, criminal Nusayri [derogatory term for ‘Alawite’] regime.’

The flag used is identical to the one pioneered by al-Qa’ida’s Iraqi branch known as the Islamic State of Iraq, and the group praises ‘Sheikh Osama Bin Laden’ in its founding statement. Yet, while the al-Qa’ida affiliation thus illustrated is not in doubt, the group’s primary focus to attack Israel has been evident from the beginning.

This is apparent in the reference to the obligation of ‘the people of Tawhid [monotheism]’ to heed the ‘screams of al-Aqsa and the moans of prisoners under the grip of the enemy Jewish cowards.’ The founding statement includes in its conclusion a call for God to defeat ‘the Jews and the kuffar.’

In a video from October of last year, the Majlis likewise vowed to fight the Jews as enemies of God. In the wake of an April 2013 rocket attack on Eilat, the group released a video, part of which featured scenes of Jews praying at the Western Wall, denounced by the Majlis as the ‘Judaization of al-Aqsa.’ The video then continues with the recurring theme of treatment of Muslim prisoners by Israel.

MSM and Hamas

The focus on Israel is also made clear by the fact that the organization maintains a presence among Salafist jihadists located in the Gaza Strip. In light of Hamas’ detention and torture of jihadist individuals, the Majlis has on more than one occasion raised the issue of Hamas’ conduct towards Salafist militants.

For example, a senior Salafist in Gaza affiliated with the Majlis recently affirmed: ‘We will continue the jihad regardless of the stance of Egypt or Hamas,’ adding that the Majlis has ‘precise knowledge on the complete cooperation between Egypt and Hamas in the war against the Salafists.’

In a similar vein, the Majlis recently released a statement calling for the release of all Salafist detainees held prisoner by the Hamas government: ‘Everyone who has a free voice and noble pen, and everyone who has a living conscience and faith should raise his voice to pressure the dismissed government to put a stop to its pursuit against the rights of its mujahideen.’

Criticism of Hamas has been a recurring theme in Salafist discourse. A very noteworthy example is a Salafist-Jihadist video (NB not from an al-Qa’ida affiliate) from about a year ago that purports to document evidence on numerous counts of Hamas’ perpetrating- in the words of the video title- ‘massacres…in Gaza against the Salafist mujahideen.’

For example, at 17:40 onwards, the video offers a purportedly intercepted radio transmission from the leadership of the Izz ad-Din al-Qassam Brigades giving orders to destroy houses and a mosque frequented by Salafists with missiles.

Like the affirmation to continue jihad despite perceived Egypt-Hamas cooperation against Salafist militants, the latest call by the Majlis for Hamas to release Salafist detainees comes following the killing by Israel of a Majlis militant called Haitham Ziyad al-Meshaal, now commemorated as a ‘martyr’ in a video released by the organization.

The day before Haitham was assassinated, relatives of imprisoned Salafist militants in Gaza held a demonstration calling on Hamas’ security forces to release their detained kinsfolk. The al-Qa’ida flag’s presence may indicate that some of the imprisoned fighters in question are members of the Majlis.

It turns out that Haitham, who was targeted as a suspect behind the rocket attacks on Eilat, had once been a member of the Izz ad-Din al-Qassam Brigades but according to the Majlis, left out of disillusionment with Hamas’ participation in ‘the game of democracy’ (a reference to the 2006 legislative elections that were judged to be free) and its ‘removal of the divine Shari’a.’

One should compare this sentiment with a statement from the group that condemned Hamas, the Muslim Brotherhood and some Salafist parties (e.g. Egypt’s an-Nour) for entering into the ‘mud of democracy.’ Here is a photo of Haitham from his funeral

GUEST POST: Famous Anasheed: ‘Madin Kas-Sayf’ by Abu Ali

NOTE: As with all guest posts, the opinions expressed below are those of the guest author and they do not necessarily represent the views of this blogs administrator and does not at all represent his employer at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy.

Jihadology.net aims to not only provide primary sources for researchers and occasional analysis of them, but also to allow other young and upcoming students as well as established academics or policy wonks to contribute original analysis on issues related to jihadism. If you would like to contribute a piece, please email your idea/post to azelin [at] jihadology [dot] net. Pieces should be no longer than 2,000 words please.

Past Guest Posts:

Daveed Gartenstein-Ross and Tara Vassefi, “Perceptions of the “Arab Spring” Within the Salafi-Jihadi Movement,” November 19, 2012.

Jack Roche, “The Indonesian Jamā’ah Islāmiyyah’s Constitution (PUPJI),” November 14, 2012.

Kévin Jackson, “The Pledge of Allegiance and its Implications,” July 27, 2012.

Behnam Said, “A Brief Look at the History and Power of Anasheed in Jihadist Culture,” May 31, 2012.

Jonah Ondieki and Jake Zenn, “Gaidi Mtaani,” April 24, 2012.

Joshua Foust, “Jihadi Ideology Is Not As Important As We Think,” January 25, 2011.

Charles Cameron, “Hitting the Blind-Spot- A Review of Jean-Pierre Filiu’s “Apocalypse in Islam,” January 24, 2011.

Daveed Gartenstein-Ross, “Why Jihadi Ideology Matters,” January 21, 2011.

Joshua Foust, “Some Inchoate Thoughts on Ideology,” January 19, 2011.

Marissa Allison, “Militants Seize Mecca: Juhaymān al ‘Utaybī and the Siege of the Grand Mosque in Mecca,” June 9, 2010.

—

By Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi

When it comes to media articles on jihadism, one of the least explored aspects is the phenomenon of anasheed (‘songs’ [sing. ‘nasheed’]- distinguished in this context by lack of use of musical instruments as per a widely held Islamic view that instruments are haram). Of the munshid artists who produce songs of this type, one of the most prominent is Abu Ali, of Saudi origin.

While Aaron Zelin regularly provides links to more recent anasheed, I decided to translate the lyrics of one of Abu Ali’s most well-known songs: ‘Madin kas-sayf’ (‘Sharp Like The Sword’): famous at least in jihadist circles. The tune is in fact identical to another nasheed he composed, entitled ‘It blew like the wind’– a song that does not refer to jihad but rather calls for the revival of the Ummah’s glory and encourages believers to seek knowledge and help each other out (in the Youtube video linked to for ‘It blew like the wind’, the user has misidentified it as ‘Sharp like the Sword’).

Given the glorification of suicide bombing that becomes very clear towards the end, the reference to ‘the occupier’ and al-Aqsa, one might expect that this nasheed was composed around the time of the Second Intifada, which saw numerous instances of suicide bombings. Yet the earliest instance I know of its use is in a 48-minute video released by the Somali al-Qa’ida affiliate Harakat ash-Shabaab al-Mujahideen, entitled ‘Labbayka ya Osama’ (‘I am at your service, oh Osama’) in 2009 (H/T: Phillip Smyth).

Here is a translation:

‘Sharp like the sword, the wind, the billows in abundance.

Strong like the horse, the lion, the thunder, sparkling.

Sharp like the sword, the wind, the billows in abundance.

Strong like the horse, the lion, the thunder, sparkling.

Bold, he seeks his upheaval and sees good tidings in death.

May the Taghut of the world that only rules stones vanish.

He discards them like Ababeel that tear through his wall with fright.

He has rejected humiliation and has arisen, weaving his pride with might.

Like a weary fugitive has his day concealed him and passed by in concealment.

Like the roaming star, his orbit falls on the path of glory.

He was once not satisfied with the world at all, and injustice is his oppressor.

Sharp like the sword, the wind, the billows in abundance.

Strong like the horse, the lion, the night, the thunder, sparkling.

Sharp like the sword, the wind, the billows in abundance.

Strong like the horse, the lion, the thunder, sparkling.

Bold, he seeks his upheaval and sees good tidings in death.

May the Taghut of the world that only rules stones vanish.

He discards them like Ababeel that tear through his wall with fright.

He hearkened unto glory when Al-Aqsa summoned its revolutionaries.

He chanted, filled with longing for death, and proceeded to play his lute.

The occupier set up his trickery, and his broker was seduced by it.

He molded the words as promises, he embroidered his dialogue with deception.

Sharp like the sword, the wind, the billows in abundance.

Strong like the horse, the lion, the thunder, sparkling.

Sharp like the sword, the wind, the billows in abundance.

Strong like the horse, the lion, the thunder, sparkling.

Bold, he seeks his upheaval and sees good tidings in death.

May the Taghut of the world that only rules stones vanish.

He discards them like Ababeel tears through his wall with fright.

They cultivated his path in fright, they imposed his blockade with starvation.

So he advanced; cunning did not divert him, even as it summoned its false steps.

How preposterous! He makes a truce until he should wipe away his shame with might.

A volcano of faith; this Talmud is his frenzy.

Sharp like the sword, the wind, the billows in abundance.

Strong like the horse, the lion, the thunder, sparkling.

Sharp like the sword, the wind, the wave in abundance.

Strong like the horse, the lion, the billows, sparkling.

Bold, he seeks his upheaval and sees good tidings in death.

May the Taghut of the world that only rules stones vanish.

He discards them like Ababeel that tear through his wall with fright.

So he [the occupier] built his strongholds in fear, he raised his walls in them.

So he [the mujahid] blew himself up among them in anger; he fixed his nails in them.

You see him as splinters of fire; a commando makes his raid.

He did not slow down his pace until he carried out his decision in death

Sharp like the sword, the wind, the billows in abundance.

Strong like the horse, the lion, the thunder, sparkling.

Sharp like the sword, the wind, the billows in abundance.

Strong like the horse, the lion, the thunder, sparkling.

Sharp like the sword, the wind, the billows in abundance.

Strong like the horse, the lion, the thunder, sparkling.

Sharp like the sword, the wind, the billows in abundance.

Strong like the horse, the lion, the thunder, sparkling.

Bold, he seeks his upheaval and sees good tidings in death.

May the Taghut of the world that only rules stones vanish.

He discards them like Ababeel that tear through his wall with fright.’

Explanatory Notes:

Taghut- An Islamic term used to describe idolatry and error. It is one of a group of words that occur in the Qur’an with the –ut termination (cf. ملكوت- ‘kingdom’, especially as in the ‘Kingdom of God’). In the 19th century, Geiger contended that the word is of Rabbinical Hebrew origin, since, he said, ‘no pure Arabic word’ ends with the –ut termination. In any event, the etymology is a matter of much dispute; for an attempt to connect the term with Ethiopic, see this discussion by Gabriel Said Reynolds.

Ababeel– Mentioned in Qur’an 105:3 (in the chapter known as ‘The Elephant’). These are apparently birds sent by God against an Aksumite force that tried to conquer Mecca in the 6th century, driving off the invaders with stones.

How preposterous! He makes a truce until he should wipe away his shame with might– Appears to be a reference to how some Islamist militants interpret the concept of hudna (Arabic for ‘ceasefire’). The idea is to sign a truce with your enemy and then wait until you think you have the upper hand, at which point you should resume hostilities.

Alternative Reading (Update and Revision: 26 May 2013)

On account of the quality of the recording, multiple interpretations can arise as regards the transcription of the Arabic lyrics. I have listened to this nasheed a number of times and I think one can propose some plausible alternatives:

*- Alternatively, this line could be transcribed as ‘نازل طاغوت الدنيا, لا يملك غير حجارة’ (‘He has clashed with the Taghut of the world. He has possession of nothing except stones’). The next line would then be referring to how he throws those stones, presumably at the occupier.

Translation of Arabic lyrics by Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi, who is a Shillman-Ginsburg Fellow at the Middle East Forum and a student at Brasenose College, Oxford University. His website is https://www.aymennjawad.org

EXCLUSIVE GUEST POST: The Indonesian Jamā'ah Islāmiyyah's Constitution (PUPJI)

NOTE: As with all guest posts, the opinions expressed below are those of the guest author and they do not represent the views of this blogs administrator and does not at all represent his employer at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy.

Jihadology.net aims to not only provide primary sources for researchers and occasional analysis of them, but also to allow other young and upcoming students as well as established academics or policy wonks to contribute original analysis on issues related to jihadism. If you would like to contribute a piece, please email your idea/post to azelin [at] jihadology [dot] net. Pieces should be no longer than 2,000 words please.

The below guest post is from the Australian Jack Roche who is a former member of Jamā’ah Islāmiyyah. Roche was trained in an al-Qaeda camp in Afghanistan and was arrested in November 2002 for a plot against the Israeli Embassy in Canberra, Australia. Roche later said that he did not intend to carry out the plot. After his arrest Roche helped provide vital information and intelligence on al-Qaeda and Jamā’ah Islāmiyyah. Roche was convicted to four and a half years in prison, and was released in May 2007 after serving his time. Below he explains Jamā’ah Islāmiyyah’s constitution based on his perspective and background. He also has provided an English translation of the entire constitution, which you can read here.

Past Guest Posts:

Kévin Jackson, “The Pledge of Allegiance and its Implications,” July 27, 2012.

Behnam Said, “A Brief Look at the History and Power of Anasheed in Jihadist Culture,” May 31, 2012.

Jonah Ondieki and Jake Zenn, “Gaidi Mtaani,” April 24, 2012.

Joshua Foust, “Jihadi Ideology Is Not As Important As We Think,” January 25, 2011.

Charles Cameron, “Hitting the Blind-Spot- A Review of Jean-Pierre Filiu’s “Apocalypse in Islam,” January 24, 2011.

Daveed Gartenstein-Ross, “Why Jihadi Ideology Matters,” January 21, 2011.

Joshua Foust, “Some Inchoate Thoughts on Ideology,” January 19, 2011.

Marissa Allison, “Militants Seize Mecca: Juhaymān al ‘Utaybī and the Siege of the Grand Mosque in Mecca,” June 9, 2010.

—

PUPJI: Pedoman Umum Perjuangan Jamaah Islamiyah (General Guidelines for the Struggle of (an/the) Islāmic Group)

By Jack Roche

PUPJI was a document produced by the Indonesian based group JI, that is, Jamaah Islamiyah – the Islāmic Group. Once produced, production was merely the photo-copying, scanning or retyping of an extant original. It was only available to high-ranking members within the group (as attested to by Nasir Abas [a former high ranking member of JI] in his book)…‘the Amir of Al Jamaah al Islāmiyah, daily executive Amir (a person who has authority like the Amir), members of the Markaziy (Majlis Qiyādah Markazīyah) – Central Command Administration, and regional leaders as well as staff members (Majlis Qiyādah Wakālah – Proxy Command Administration)’.[1] [2]

In order to partially answer why it was that PUPJI was not made available to rank and file members, it is perhaps prudent to refer to a statement given by Nasir Abas:

‘…knowledge of PUPJI is restricted to the level of leader and above alone. Other members are guided and given instructions without the knowledge that those guidelines and instructions originate from the book of guidelines for the daʿwah of Al Jamaah al Islāmiyah, namely PUPJI, and without in fact having any knowledge of PUPJI. Likewise also, not all members of the Al Jamaah al Islāmiyah organization have ever physically seen the book of PUPJI but there are those who have knowledge of its existence or have heard of it but never actually seen it.’[3]

Whilst this does not completely answer the question of why the restricted availability of PUPJI, it does signpost guidance and instruction within JI being given by those personnel that have been made privy to PUPJI. Were it to be the case that copies of PUPJI were made available to each and every member of JI, then without correct supervision all manner of individual interpretations would abound. Such a system would be no system at all other than a form of anarchy. The distribution of PUPJI is therefore a managerial strategy, one that aligns itself with Islāmic methodology (namely that command comes from above) and ‘those personnel that have been made privy’, that is those individuals who possess a reasonably high degree of Islāmic knowledge and/or knowledge of the mechanisms and objectives of JI as a whole as well as leadership skills, are tasked with disseminating the precepts contained within PUPJI towards those members of JI tasked under their care.

PUPJI describes itself as,…‘a general objective that is able to provide a systematic overview for the motivational steps of a jamāʿah that integrates careful, objective standardized principles and operational measures’. This clause of PUPJI gels with the description given by Nasir Abas, that it was ‘…conferral of a systematic illustration of the Jamaah’s steps which are cohesive between the principal values (Islām) and the undertaking of actions that are prudent, guided, and regulated’.[4] It is within this context that it acts as a ‘guide-book’ or ‘book of guidelines’ for the workings of a/the jamā‘ah – that is a group that functions within and along Islāmic principles. For these reasons one often hears it described as JI’s constitution.

JI was officially formed around January of 1993 when some members of NII (Negara Islām Indonesia – Islāmic State of Indonesia) group broke away from its leadership. The breakaway members were ‘lead’ by ‘Abdullāh Sungkar and Abū Bakar Ba’asyir. Many of the members of NII had undergone training in Afghanistan under the auspices of such individuals as Shaikh ‘Abdur-Rabb rasul Sayyaf. Whilst the members of JI were now detached from NII, they were still able to make use of whatever facilities were available for training in Afghanistan.

As a group/organization, NII possessed ‘state statutes’.[5] This is something that is often overlooked when examining the genealogy of JI, that is it is seldom made mention of. These ‘state statutes’ had been drawn up by, amongst others, S. M. Kartosoewirjo when he proclaimed the Islāmic Nation of Indonesia (NII) in a regional area in West Java on the 7th of August 1949. According to Nasir Abas, they were in book form and known as ‘Pedoman Dharma Bhakti’ (Negara Islam Indonesia) – ‘Manual of Devotional Obligations’ (Islāmic State of Indonesia) and ‘Qanun Asasi’ (sometimes referred to as Qanun Azasi) – ‘Founding Principles’ or ‘Statutes’, ‘Constitution’).[6]

In fact, ‘Pedoman Dharma Bhakti’ was a conglomeration of a number of smaller publications. These included, ‘Qanun Azasi’, ‘UU Hukum Pidana’ (Criminal Laws), ‘Maklumat Imam’ (Edicts of the Leader), ‘Maklumat Militer’ (Military Edicts), ‘Maklumat Komandemen Tertinggi’ (High Command Edicts), ‘Statement Pemerintah’ (Government Statement), and ‘Manifesto Politik’ (Political Manifesto). It is reasonable to determine that PUPJI was in fact a revised version of those publications.

Whilst ‘Pedoman Dharma Bhakti’ was written in Indonesian, PUPJI was written in both Indonesian and Arabic, wherein the main text is Indonesian and ‘references’ being in Arabic. ‘References’ within the document are quotations from Al Qur‘ān and the aḥādīth (‘sayings’) or Sunnah (sayings, non-sayings, actions or non-actions of the Prophet Muḥammad).

I was taught in 1996/97 that the principles upheld by JI towards the individuals within the group, and as such inculcated and practiced, were in accordance with those adhered to and upheld as belonging to the ‘aqīdah (belief) of the Ahlus Sunnah wa’l Jamā‘ah minhajus-Salafuṣ-Ṣāliḥ. The beliefs of the Ahlus Sunnah wa’l Jamā‘ah is the belief and method of that which the Messenger of Allāh came with, and how his Ṣaḥābat understood this belief and their application of this method.

Ahlus Sunnah wa’l Jamāfiah minhajus-Salafuṣ-Ṣāliḥ is explainable as:

Those who adhere to the Sunnah [of the Prophet Muḥammad] and who are assembled together in a group and who follow the methodology and practices of the Pious Predecessors. The ‘Pious Predecessors’ are the 1st three generations of Muslims, namely:

- The Prophet Muḥammad and his Ṣaḥābat (companions who followed the Prophet Muḥammad in his application of the Deen (religion) of Islām);

- The Tābi‘īn (followers of the Ṣaḥābat);

- The Tābi‘at-Tābi‘īn (followers of the followers of the Ṣaḥābat)].

The basis of Ahlus Sunnah wa’l Jamā‘ah is upon such aḥādīth as:

It was narrated from ‘Awf bin Mālik that the Messenger of Allāh said: “The Jews split into seventy-one sects, one of which will be in Paradise and seventy in Hell. The Christians split into seventy-two sects, seventy-one of which will be in Hell and one in Paradise. I swear by the One in Whose Hand is the soul of Muḥammad, my nation will split into seventy-three sects, one of which will be in Paradise and seventy-two in Hell.” It was said: “O Messenger of Allāh who are they?” He said: “Al Jamā‘ah – The main body.” (Sunan Ibnu Mājah 3992).

And:

“…adhere to my sunnah and the sunnah of the rightly guided caliphs…” (Sunan At-Tirmidhī 2685).

The general principles espoused within PUPJI are influenced by the likes of such people as Muḥammad bin ‘Abdul-Wahhāb, Abū’l A‘lā Maudūdī, and Sayyid Qutb. This would also have been the case for many of the precepts contained within the ‘state statutes’ of NII. However, since PUPJI was drawn up in 1996, its precepts were also influenced by the likes of ‘Abdullāh fiAzzam, Ayman Aẓ-Ẓawāhirī, and Usāmah bin Lādin, amongst others. This influence is in no small part due to the presence of NII members under training

GUEST POST: The Pledge of Allegiance and its Implications

NOTE: As with all guest posts, the opinions expressed below are those of the guest author and they do not necessarily represent the views of this blogs administrator and does not represent at all his employer at the Washington Institute for Near East.

Jihadology.net aims to not only provide primary sources for researchers and occasional analysis of them, but also to allow other young and upcoming students as well as established academics or policy wonks to contribute original analysis on issues related to Global Jihadism. If you would like to contribute a piece, please email your idea/post to azelin [at] jihadology [dot] net. Pieces should be no longer than 2,000 words please.

Past Guest Posts:

Behnam Said, “A Brief Look at the History and Power of Anasheed in Jihadist Culture,” May 31, 2012.

Jonah Ondieki and Jake Zenn, “Gaidi Mtaani,” April 24, 2012.

Joshua Foust, “Jihadi Ideology Is Not As Important As We Think,” January 25, 2011.

Charles Cameron, “Hitting the Blind-Spot- A Review of Jean-Pierre Filiu’s “Apocalypse in Islam,” January 24, 2011.

Daveed Gartenstein-Ross, “Why Jihadi Ideology Matters,” January 21, 2011.

Joshua Foust, “Some Inchoate Thoughts on Ideology,” January 19, 2011.

Marissa Allison, “Militants Seize Mecca: Juhaymān al ‘Utaybī and the Siege of the Grand Mosque in Mecca,” June 9, 2010.

—

By Kévin Jackson

Defining al Qa’ida’s membership has always represented a divise issue among analysts. I’ll approach this topic by focusing on a fundamental practice commonly used by jihadi organizations, namely vowing an oath of allegiance or bay’a.

In a nutshell, the bay’a procedure constitutes the cornerstone defining one’s membership. A longstanding ritual featuring in the early Islamic tradition, giving bay’a (individually or collectively) consists in recognizing the legitimacy of a group/state leader authority. The covenant between the amir (leader) and the one who gives the bay’a lies in listening and obeying, in hard and easy times, as long as the amirship follows the right path. Rendering allegiance to the amir of al Qa’ida, for example, would thus imply not to dispute his and/or al Qa’ida’s commanders’ directives and to fully support the organization’s agenda.

The Bay’a has been institutionalized within the jihadi milieu for the doctrinal foundations it acts upon stress the mandatory aspect of such a practice. Given that joining a jama’ah (group) of mujahidin is seen as an obligation (wajib) upon every Muslim and cannot be done except with a pledge of allegiance, the bay’a is thus considered as such too. From an organizational perspective, these doctrinal regulations secure the loyalty and cohesion within the ranks, while preventing core attrition by tightly binding new recruits through a formal covenant.

It is worthwhile underlining the contractual aspect of this longstanding ritual drawing lines of demarcation between jihadi organizations. If the one giving the oath promises to listen and obey whatever the hardships, the one receiving it is also entitled to fulfill his obligations as the amir. This counterpart from the leader amounts to a continuous commitment to respect the covenant provisos and serve the interests of Islam and Muslims through the policy he implements. The amirship also requires certain characteristics, which, for al Qa’ida, revolve around knowledge, experience, ethical qualities, etc.

On the other hand, a bay’a has to be accepted before one can be considered as a sworn member/organization. This decision falls upon the amir‘s goodwill and depends on the extent to which would-be comers meet the required criteria prescribed by the organization leadership. As a result, groups rendering their allegiance to Ayman al Zawahiri cannot be labeled al Qa’ida in the absence of an official recognition from the Pakistan-based leadership. This explains why assertions dubbing some al Qa’ida’s affiliates/franchises on the only basis that an oath has been sworn should be met with skepticism at the very least.

For example, while Harakat al Shabab al Mujahidin had pledged their loyalty to Usama bin Ladin in September 2009, the Somali group couldn’t be portrayed as being part of al Qa’ida without any further confirmation by the mothership in the Pakistan’s tribal areas. This changed only after February 2012, following a joint statement of Ayman al Zawahiri (amir of al Qa’ida) and Mukhtar Abu’l Zubayr (amir of al Shabab), where the Egyptian officially accepted al Shabab under al Qa’ida’s direction. This is the type of acknoweldgement which should be looked at to draw accurate distinctions between jihadi factions.

A cherished autonomy

Well-understood by jihadis, the binding burden of the oath can be sensed through the lens of militants’ own trajectory. The life story of Khalid Shaykh Muhammad (KSM) is a case in point. Even after having moved to Kandahar to work directly with al Qa’ida’s leadership in the late 1990’s, the 9/11 mastermind was still reluctant to formally join. Translation: while he had decided to play on al Qa’ida’s team via close work relationships, he was still refusing to swear allegiance to bin Ladin so as to maintain his operational room for manoeuvre. KSM became a core member only after 9/11 attacks were carried out, following pressures from his peers arguing that the persistent refusal of someone with his pedigree would establish a worrisome precedent for others.

Given how the pledge of allegiance undermines one’s autonomy, it should not come as a surprise that others have shared KSM’ sentiments by postponing the bay’a as long as they could or simply rejected it.

Before bin Ladin formally declared Mulla Muhammad Umar as his direct leader, the Saudi and his entourage made their best to avoid this option to ensure a complete freedom to their global jihad. Notwithstanding external pressures and an increased tense context, the late amir of al Qa’ida still kept using pretexts to shelve a proposal put forward by Abu’l Walid al Misri, a respected senior Egyptian mujahid, designed to improve his relationship with the Afghan Taliban leader. Bin Ladin eventually resigned himself to perform the bay’a in late November 1998 but (and this is a big one) only through Abu’l Walid acting as his proxy. The indirect oath would enable bin Ladin to play it both ways according to the circumstances and as a result, despite being virtually tied by his pledge, still retain his independence. And indeed, the following years, bin Ladin continued to by-pass Mulla Umar’s instructions, namely stopping his media campaign and external operations against the US.

Also instructive is Abu Jandal’ story, which outlines another way of keeping one’s room for manoeuvre. The Yemeni, along with some of the group of combatants he came with, vowed allegiance to bin Ladin after a three-day meeting with the al Qa’ida’s leader in Jalalabad in 1997. Except that it was not an integral but a conditional one. Hence, while Abu Jandal had accepted bin Ladin as his leader in Afghanistan, the deal was that he will not take his orders from the Saudi should he be in another battlefield. Later in 1998, the then bin Ladin’s bodyguard decided that the time has come and eventually pledged an unconditional oath, thereby making him a core member of al Qa’ida.

Muhammad al Owhali’s interrogation provides a further insightful glimpse into the meaning of the bay’a in terms of command and control, as well as the wariness it provokes among some. The 1998 East Africa bombing operative told his FBI interrogators that his refusal to formally join al Qa’ida, despite having been urged to do so, was linked to his fear that, once a core member, he might end up working in non-military activities while having a strong desire in armed jihad. His non-membership would thus enable him to accept or refuse a mission assigned to him by al Qa’ida’s leaders/ commanders according to his own will. As put it in his interrogation: « Once you take the bayat you no longer have a choice in what your missions would be. »

Theses various episodes clearly outline the concrete implications of pledging an oath of allegiance and also explain jihadis’ lack of promptness in giving it. Not

GUEST POST: A Brief Look at the History and Power of Anasheed in Jihadist Culture

NOTE: As with all guest posts, the opinions expressed below are those of the guest author and they do not necessarily represent the views of this blogs administrator and does not represent at all his employer at the Washington Institute for Near East.

Jihadology.net aims to not only provide primary sources for researchers and occasional analysis of them, but also to allow other young and upcoming students as well as established academics or policy wonks to contribute original analysis on issues related to Global Jihadism. If you would like to contribute a piece, please email your idea/post to azelin [at] jihadology [dot] net. Pieces should be no longer than 2,000 words please.

Past Guest Posts:

Jonah Ondieki and Jake Zenn, “Gaidi Mtaani,” April 24, 2012.

Joshua Foust, “Jihadi Ideology Is Not As Important As We Think,” January 25, 2011.

Charles Cameron, “Hitting the Blind-Spot- A Review of Jean-Pierre Filiu’s “Apocalypse in Islam,” January 24, 2011.

Daveed Gartenstein-Ross, “Why Jihadi Ideology Matters,” January 21, 2011.

Joshua Foust, “Some Inchoate Thoughts on Ideology,” January 19, 2011.

Marissa Allison, “Militants Seize Mecca: Juhaymān al ‘Utaybī and the Siege of the Grand Mosque in Mecca,” June 9, 2010.

—

By Behnam Said

At the moment, I am working on my PhD-project on “Militant hymns (anasheed jihadiya) as a part of the Jihadist culture”. This culture I consider to be more effective in terms of propaganda and social cohesion than any ideology alone could be. Young radicals all over the world are listening to the nasheeds extensively – a fact, authorities are getting more and more aware of, as court papers and other sources show. Some of the most interesting findings (which are actually a lot) I will outline in an article to be published in November for Studies in Conflict and Terrorism. Until then Aaron gave me the opportunity to share at least some facts with the readers of “Jihadology” in advance.

Background

Nasheeds, as you all are aware of, are an integral part of almost every Jihadist video production. For example, we see al-Qaeda members in action on the battlefield accompanied by the soundtrack of a smooth a cappella song. On relevant internet forums and websites you will find a bulk of these nasheeds as mp3-files, sometimes even complete collections. There are also plenty of videos with these songs on YouTube. It appears as if no Jihadist can establish his YouTube channel without posting at least a few militant hymns. On Facebook there are also groups publishing militant nasheeds that obtain more than 10,000 “likes”.

Not all of the songs which are popular in the Jihadist scene are new. Many of them are based on songs which were included in the songbooks of the 1980s and in poems of the so called shu´ara ad-da´wa, a branch of poetry which began in the 1950s and ended approximately in the 1980s. For example one of the most popular songs at the moment is “Bi-Jihadina”, which is actually a song by Abu Mazin, a popular Syrian munasheed, who recorded it either in the late 70s or the early 80s. There is also one example of a song used in videos of the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) based on a poem by Muhammad Iqbal (1877-1938), the famous Pakistani poet, that has been translated to Arabic. Some other nasheeds, like the Somali ash-Shabab song “Rayatu t-Tauhid” or some AQAP songs, are contemporary.

The fascination of these songs is described by Samir Khan, the former editor of Inspire, in an article for Inspire:

I remember when I traveled from San´a, for what seemed like years, in a car to one of the bases of the mujahidin, the driver played this one nashīd repeatedly. It was “Sir ya bin Ladin”. I already knew of this nashīd from before, but something had struck me at that moment. The nashīd repeated lines pertaining to fighting the tyrants of the world for the purpose of giving victory to the Islamic nation. But it also reminded the listener that Shaykh Usama bin Ladin is the leader of this global fight. I looked out of the window at the tall mud houses below the beautiful sky and closed my eyes as the wind blew through my hair.”

This personal experience by Khan finds its equivalent in many theoretical descriptions of the desired effects of nasheeds on young people. The oldest sources in this context I found in some nasheed collections from the 1980s. Here it is clearly said, that nasheeds are an instrument to awaken the wish for martyrdom and self sacrifice in the hearts of young Muslims and to give them strength for da´wa and Jihad.

You can categorize nasheeds in accordance with the topics they cover. Often you will find that the poems fit into categories of classical poetry, for example:

- Mourning songs

- Praising songs

Other categories are more modern:

- Prisoners songs

- Songs regarding ongoing political processes (for example the battle for Syria)

- Palestine songs

But most of the songs I analyzed can be described as “battle songs”. Focusing on war and ones fighting group, which is described as heroic and brave in antipode to the tyrannical and oppressive enemy (taghut). Here I am not sure if such hymns can be described as classical by category, because the language of such songs are very Jihadist.

Legality and Influence

It is also interesting to have a look at the different legal stances towards nasheeds, especially from Salafi and Wahhabi scholars. I was surprised to find most of them skeptical towards nasheeds. They consider them allowed (mubah), but only under strict conditions regarding form (a cappella only) and content (purely Islamic and Jihad-supportive). So I tried to figure out why the Jihadists are making use of nasheeds so extensively even though Salafi and even more Wahhabi scholars underline the importance of limiting listening to nasheeds. The answer, I think, lies in the history of the nasheeds, which I mentioned above. Modern nasheeds have their origin with the Muslim Brotherhood (MB) and its radical branches in the Levant and in Egypt. From here they made their way to the Arabian Peninsula where nasheeds were known at least from the 70s on, but became more popular in the early 90s during the sahwa-period as sources underline. The stance of MB ideologues was always more positive towards music than that of the Wahhabis and Salafis. Nasir ad-Din al-Albani for example criticized articles from the 50s published in the MB magazine which called for “Islamic music”, which he called as absurd as “Islamic Communism”. So the addiction of Jihadis to nasheeds reflects the influence of the MB on the militant movement. The only clear influence on nasheeds by the Salafis/Wahhabis is the Jihadist adoption of the strict prohibition of any music instruments, except the use of hand drums in some cases.

The Jihadist culture thus is – like the movement itself – a merging of MB and Salafi/Wahhabi ideology. But in this case the MB influence is absolutely overwhelming and it shows that the culture of the MB and its militant branches is more crucial for the Jihadis than some might assume.

I hope that I hereby provided you some input for discussions about the history of Jihadism and its culture as well as about the relevance of this culture.

Behnam Said has studied Islamic Science, Political Science, and History in Hamburg, Germany. His main fields of interest are the relation of Sunna and Shia, history and culture of modern Afghanistan, and political and militant Islamism. Beside his current job as an intelligence analyst he is doing his PhD at the University of Jena on the topic of militant nasheeds. A more in depth version of this post will be published in a forthcoming issue of the academic journal “Studies in Conflict and Terrorism.”

GUEST POST: Gaidi Mtaani

NOTE: As with all guest posts, the opinions expressed below are those of the guest authors and they do not represent the views of this websites administrator.

Jihadology.net aims to not only provide primary sources for researchers and occasional analysis of them, but also to allow other young and upcoming students as well as established academics or policy wonks to contribute original analysis on issues related to Global Jihadism. If you would like to contribute a piece, please email your idea/post to azelin [at] jihadology [dot] net. Pieces should be no longer than 2,000 words please.

Past Guest Posts:

- Joshua Foust, “Jihadi Ideology Is Not As Important As We Think,” January 25, 2011.

- Charles Cameron, “Hitting the Blind-Spot- A Review of Jean-Pierre Filiu’s “Apocalypse in Islam,” January 24, 2011.

- Daveed Gartenstein-Ross, “Why Jihadi Ideology Matters,” January 21, 2011.

- Joshua Foust, “Some Inchoate Thoughts on Ideology,” January 19, 2011.

- Marissa Allison, “Militants Seize Mecca: Juhaymān al ‘Utaybī and the Siege of the Grand Mosque in Mecca,” June 9, 2010.

—

By Jonah Ondieki and Jake Zenn

Al-Shabbab introduced the world’s first Swahili jihadi magazine on April 5, 2012 called Gaidi Mtaani, meaning “On Terrorism Street.” In “On Terrorism Street” al-Shabbab subtly mocks the Kenyan army’s Operation Linda Nchi (“Defend the Nation”) by naming its own operation, Operation Linda Uislam (“Defend Islam”). The online magazine’s colourful style and well-edited and formatted articles places it among the elite of online Jihadist publications, similar to al-Qaeda’s now inactive Inspire and the Turkistan Islamic Party’s (TIP) Islamic Turkistan.

As always, the language of choice for this publication, Swahili, matters. Evidently, al-Shabbab wants to appeal to the Kenyan street. Al-Shabbab’s own constituency in Somalia would only understand Somali and, to a lesser extent, Arabic. Kenyan elites would be more attracted to an English publication than Swahili given that English is the language of education and the upper class in Kenya. Al-Shabbab may be trying to win over lesser-educated Muslims in Northern Kenya to al-Shabbab’s cause or to convince Kenyans of all stripes that the propaganda they see on television about the Kenyan army’s success in Somalia is untrue.

Alternatively, the publication may be a way for al-Shabbab to tell jihadis that al-Shabbab considers Kenya another one of its enemies, as evidence by the use of Swahili—not English, Somali or Arabic. On the Somali online jihadi forum, al-Qimmah, al-Shabbab has released other warnings to the Kenyan government, but the “Gaidi Mtaani” publication in Swahili, which was released on the Shamukh al-Islam forum, will reach a more diverse audience than statements on al-Qimmah.

Below is a summary translation of some of the main points included in the publication:

Operation Linda Uislam (Operation protect Islam)

Many Muslims believe that any attack on them (such as the incursion of Kenyan Defense Forces (KDF) into Somalia) is instigated from the West. The basis that Kenya used to start the attack was not sufficient to justify its attack on al-Shabbab, but was part of the wider scheme of the influence of the unbelievers (kafir) of the Western world. The reason was a mere fabrication to validate their attack on Islam.

It is clear that the Western media has been successful in shading Muslim believers in a bad light. It has created an impression that the believers of God, who are fighting according to God’s will are followers and sympathizers of terrorism. The Western journalists are experts of deceit who have even managed to deceive some Muslims to believe their slander!

The fact is that they are trying to misrepresent the mujahidin by spreading false information and magnifying their small mistakes to look like big crimes. They are sowing a seed of hatred amongst them, their leaders and followers. On the other hand, they seem to praise the West and justify their wickedness. Therefore, Muslims are urged not to rely on such news sources until they are validated by true Islamic sources. However, some news such as that of weather can be relied on.

Protecting the Mujahidin

The prophet of God (Mohammad) says, “Whoever shall protect the reputation and name of his brother, God shall deliver his face from the furnace of jehannam (hell) at the day of judgement (from Al Tirmithi).” He continues saying that, “anybody who shall betray a fellow Muslim, his reputation shall be destroyed and God will forsake him at the time of need…” therefore Muslims are urged to defend their Muslim brothers all the time.

The British Betrayal of Muslims

History is very clear about how the British related with Muslims in the East African coast in the colonial period. The massacre, persecution and other inhumane acts that they did to Muslims are evidence of how they hate humanity. Their image today of being in the front line in defending human rights is superficial because underneath lies the crimes against humanity they perpetrated especially on Muslims. The British activities of fighting Islam are well known and are not a new thing. For example they took Palestine’s land and gave it to Jews. This is a proof that they can take land that duly belongs to Muslims and give it to their enemies.

In the case of East Africa; in 1895, the British government was given a coastal strip of 10 miles by the Sultans of Zanzibar. These Zanzibar leaders entered into a treaty which had one of its articles state that “Britain will not apply any Christian law on any party of the coast UNLESS Kenya attained independence or they consent to change the religion of the coast six months in advance.” These unwise poor sultans of Zanzibar made religion a commodity for transaction with the British authorities.

In the Lancaster meeting of 1962-63 which was to write the Kenya constitution, it was agreed that that coastal strip shall remain under the jurisdiction of the independent Kenyan government. We are not trying to mean or imply that the coastal Kenya should secede from the mainland Kenya. Not at all! We are trying to make the reader to understand how the Islamic religion was joked about.

Britain was a key player in dislodging Palestinians in favour of the Jews and selling the Muslim land in the Kenyan coast to the Kenyan government. Today the same thing is happening in Somalia where they are assisting to cast down Islam that is defended by al-Shabbab. They have been envying the Islamic growth in Somalia for the past 20 years, thus they now support the AMISOM, Ethiopian troops and now the KDF incursion into Somalia to disrupt the Islamic systems. But their efforts will not prevail over God.

The recent London Conference on Somalia was sponsored by Britain. The inner motive was to topple the Islamic systems by collaborating with Kenya together with other African countries and the world. If you carefully look at what is going on in Kenya and Somalia then you will vividly understand the real intention.

Just a few days before the conference, Kenya had given a contract to Total to start exploring oil on the coast. Later we saw British and American companies sign a contract to mine oil in Puntland. Moreover, just the other day we saw the Kenyan president, Ethiopian PM and the South Sudan president converge in Lamu to launch the construction of the Port of Lamu. It is sad that other nations are using the Somalia situation to advance their economic development instead of helping Somalia back to peace by strengthening Islam because Somalia was peaceful when it was under Islamic rule.

If Kenya is going to be the Israel of Africa and Somalia the Palestine of Africa then we must not allow that. Every Muslim wherever you are ask yourself whether you are defending Islam from attack by the unbelievers (kafir) or you are supporting the attack.

10 ways of recognizing an undercover spy

- He will disguise himself and start establishing friendship with the one he is interested in investigating just as a normal person.

- A few elements of lies will start surfacing. You will note this when he will use long explanations to defend himself whenever he contradicts himself. For example he may claim to be a college student and you may see him in a cyber cafe or the mosque

GUEST POST: Jihadi Ideology Is Not As Important As We Think

NOTE: As with all guest posts, the opinions expressed below are those of the guest author and they do not necessarily represent the views of this blogs administrator.

Jihadology.net aims to not only provide primary sources for researchers and occasional analysis of them, but also to allow other young and upcoming students as well as established academics or policy wonks to contribute original analysis on issues related to Global Jihadism. If you would like to contribute a piece, please email your idea/post to azelin [at] jihadology [dot] net. Pieces should be no longer than 2,000 words please.

See here for previous posts in this exchange:

- Daveed Gartenstein-Ross, “Why Jihadi Ideology Matters,” January 21, 2011.

- Joshua Foust, “Some Inchoate Thoughts on Ideology,” January 19, 2011.

—

By Joshua Foust

On January 21, Daveed Gartenstein-Ross wrote a detailed argument for why the study of “jihadi ideology” is important. He raised some really interesting points that inspired a great deal of thinking on my part, and I’m grateful he took the time to respond. I have to confess, however, that I am left more confused than ever about why we should focus so much on ideology, and not other things instead. It remains unclear to me how ideology affects behavior, or how its study can help us understand or predict the decisions and choices of would-be terrorists.

For example, Daveed is absolutely correct that I erred in describing ideology as a sole cause of behavior. I admit I was a bit confused when he later called ideology, “a robust explanation for both terrorist radicalization and also terrorist actions,” as that seemed to imply a sole-cause argument, but I did not intend to argue the point so I withdraw it.

However, I found myself lost in trying to figure out the other aspects of studying the concept of ideology as an analytic construct. For example, even if ideology is only a partial cause or inspiration for behavior, we should still be able to describe how ideology causes or inspires behavior. But I have never, in the many papers I’ve since read on Jihadi ideology, read of a mechanism by which ideology inspires or causes behavior—only a lot of stories, and plenty of people who did something that they claimed was inspired by ideology. This begs the question: if we don’t know how ideology influences behavior, then how can I analyze it or declare it important for studying jihadism? And while Daveed’s post has a great deal of information, I don’t see in it, or in the study he wrote, a description of this causal mechanism.

I think, too, that any discussion of ideology—especially when dealing with a celebrity like Anwar al-Aulaqi, as my original post tried to do—must deal with the question of false positives and false negatives. If ideology is even a partial cause of behavior, then there should be a lot of people who espouse a certain ideology that engage in a certain behavior, along with relatively few people who espouse the ideology who DO NOT engage in the behavior, and also relatively few people who DO NOT espouse the ideology who DO engage in the behavior. Otherwise we’re seeing our cause without our effect and our effect without our cause as often as we’re seeing our cause with our effect, which would suggest we’re on the wrong track. We do see a lot of false positives and false negatives in Islamist-ideology explanations of extremism. The vast, vast majority of people who espouse “salafist jihadist Islamist ideology” do not engage in terrorism. So how can we assign ideology as the reason why the tiny minority of people do things?

Which is another problem with this discussion of ideology and jihadism: begging the question. Given the fact that many people espouse radical ideologies but do not become violent extremists, it would seem that at most ideology is a necessary, but not sufficient to cause the behavior in question. If that’s the case, then what makes it sufficient? Does that thing lead to the behavior even if the ideology is absent? If it does, then there’s no reason to take ideology as an influence on behavior. It’s like saying “X causes Y only when Z is present” and “Z causes Y even if X is absent.” If both those statements are true, then you don’t need X—ideology—in either. You just need Z to predict Y.

I’m not really comfortable discussing Daveed’s personal experiences with radical Islam. His current research, however, does warrant discussion. For example, the percentages on radicalization that he provides at best fail to support his argument. At worst, they actually undermine it. About 40% of those studied became religious and then became political. About 10% became political and then became religious. And there is apparently no data on the other 50%. Since this wasn’t a random sample, we can’t assume that the 40% and 10% are representative of the larger population. That means it is entirely possible that it’s somewhere between a 60-40 and a 40-60 split, in which case the presence of religious influences would basically amount to a coin toss. The figures he provides make it entirely plausible that the presence of religion is a random factor, and therefore not so causal.

Similarly, I don’t understand why he relied on behavior to explain ideology. Daveed’s study took people who already exhibit a behavior, and then measures the extent to which they exhibit other behaviors he assumes are evidence of a specific ideology. There is no control group. This gets at the heart of the problem with false positives and false negatives: by not including people in the study who did not engage in the behavior, there is no way to assess actual behaviors. It is a significant sampling bias. Moreover, I simply don’t see how any of his examples are necessarily indicative of ideology. He argues, “Absent the prevalent ideology… there is simply no explanation for why a relatively large number of people would decide to grow their beards out in a similar way, see dogs as unclean, stop making physical contact with members of the opposite sex, et cetera.” But that doesn’t follow at all. If it were the case, then all behavior is ideological. Most people tend to behave similarly to the people they interact with – they eat similar foods, they wear similar clothes, they have similar hair styles, many people believe in the same things as their neighbors – is everything the any number of people hold in common to be automatically declared ideological? Common practices just aren’t a persuasive argument that ideology explains behavior.

I’m glad to see he didn’t rely on people’s stated beliefs—an unfortunate mistake many other researchers on ideology and jihadism commit. However, that still doesn’t avoid the false positives and negatives, begging the question, the lack of mechanisms, or the possibility that everything he found is the same as what we would expect from chance. I’m afraid I just can’t find a reason to believe it, especially when he leaps from saying ideology is important to saying who espouses the ideology is important. Even if we accepted ideology as an explanation, there’s no reason to assume ideology is tightly tied to specific people. If ideology matters, then why is it not just as reasonable to ask what the major influential components of it are, no matter who disseminates it? Why is it not just as reasonable to ask in what situations it matters, no matter what its components are and no matter who disseminates it? Or, why not be really nit-picky, and ask IF there are any disseminators, components, or situations that matter more than any others – allowing for the possibility that perhaps all options matter equally?

Viewed this way, the case for Aulaqi’s importance just doesn’t make sense. I have yet to see an explanation for why alternate hypotheses don’t apply. For example: which proponents of Islamist rhetoric were more available and accessible to western radicals than al-Aulaqi? Forensics on confiscated computers often turn up a whole host of jihadi ideologues—an ecosystem of personalities arguing for jihad. Aulaqi’s material is common, but it’s not the only thing out there. But even that is immaterial: if his speeches, by design in the English language, are just more available and accessible, then their use is more plausibly an effect or a co-occurrence, not a cause, of those people’s radicalization, just as his presence on computers similarly fails to explain lots of other people’s non-radicalization.

In a more general sense, the rejection of alternative explanations should be worrying to anyone seeking a systematic, rigorous explanation of how people radicalize and why they choose to engage in behaviors. This is the problem I have with calling Aulaqi the worst-anything, or most-anything. We just don’t know, especially because we just don’t know how the ideas he spreads affect people. All we have are correlates—not correlations—just things happening kind of at the same time for some people. While that is certainly important, and definitely deserving of detailed, rigorous research, I remain utterly confused at the certainty with which we can declare jihadi ideologues the global threat they’re portrayed to be.

GUEST POST: Why Jihadi Ideology Matters

NOTE: As with all guest posts, the opinions expressed below are those of the guest author and they do not necessarily represent the views of this blogs administrator.

Jihadology.net aims to not only provide primary sources for researchers and occasional analysis of them, but also to allow other young and upcoming students as well as established academics or policy wonks to contribute original analysis on issues related to Global Jihadism. If you would like to contribute a piece, please email your idea/post to azelin [at] jihadology [dot] net. Pieces should be no longer than 2,000 words please.

–

By Daveed Gartenstein-Ross

On January 19, Joshua Foust posted a rather interesting article at Jihadology questioning Anwar al-Aulaqi’s importance as a jihadi ideologue, and in so doing, also called into question the assumed linkage between Islamist ideology and behavior. Though Foust’s post raises interesting and valid questions, and introduces bodies of research that are often ignored in debates over terrorist radicalization, I find his conclusion problematic for three reasons. First, Foust seems to be arguing against a strawman on the question of how ideology can have an impact on behavior. Second, the applicability of his general observations about the connection between ideas and behavior is questionable in the context of Islamist ideology. And third, erecting the very high evidentiary standard with which Foust concludes his article is not at all helpful when it comes to a problem set like terrorist radicalization, which it is necessary to address now.

Strawman Opponent?

It is somewhat unclear what Foust is objecting to within the current literature on radicalization—which, in fairness, is reflected in his post’s title, “Some Inchoate Thoughts on Ideology.” But to the extent his article refutes a definable set of ideas, it seems to argue against monocausal explanations of behavior. Specifically, Foust writes:

The assumption behind the ideology discussion appears to be that behavior is a gun, and ideology is a trigger. That is, you have a person, they accept ideology, and then the output is behavior (in this case, violence). But that just isn’t how people work, and using some basic logic and self-knowledge can reveal that. We are not mono-causal creatures, even in relatively simple matters like choosing where to eat lunch.

The last point is undoubtedly correct: we are not monocausal creatures. But which authors, specifically, share this set of assumptions? A careful reading of Alexander Meleagrou-Hitchens’s Foreign Policy article that is the hook for Foust’s piece reveals no such monocausal assumption, though Meleagrou-Hitchens clearly does conclude—contrary to Foust—that ideology is important. Nor does Foust point to other authors who write about ideology as though it is the sole cause of terrorist violence.

This framing of the discussion seems designed to bolster the importance of Foust’s refutation. But the contribution an author can make by refuting a clearly exaggerated interpretation of a subject is minimal when that exaggerated interpretation does not represent the conventional wisdom in a field. And in the academic discussion of terrorist ideology, it seems that the dominant opinion among prominent scholars—including Marc Sageman, Jessica Stern, Robert Pape, Jerrold Post, and now apparently Brian Michael Jenkins—is that religious ideology is relatively unimportant. (There are of course plenty of scholars on the other side of this debate, including Mary Habeck, Assaf Moghadam, and myself.)

So let’s define the debate in a more reasonable way. The question is not whether terrorists are automatons who read something on the Internet and then act in service of that idea. They aren’t, full stop. Rather, the question is whether religious/ideological factors seem to provide a robust explanation for both terrorist radicalization and also terrorist actions.

One Man’s Experiences

Before turning to the role of al-Aulaqi specifically, I’d like to address the role that Islamist ideology has on behavior. Foust writes: “The heart of my problem with discussing Islamist ideology is that I don’t understand how it affects behavior.” This is because behavior is complex, encompassing such causal factors as “constraints, signaling from peers, intent, and capability.” On the question of how Islamist ideology can impact behavior, I believe the answer is so obvious as to be virtually indisputable. Note that Foust frames the issue as Islamist and not jihadi ideology. I don’t know whether this framing was purposeful, but I’m glad that he put the question this way, because an examination of Islamist behavior is illuminating.