The Clear Banner sub-blog on Jihadology.net is primarily focused on Sunni foreign fighting. It does not have to just be related to the phenomenon in Syria. It can also cover any location that contains Sunni foreign fighters. If you are interested in writing on this subject please email me at azelin [at] jihadology [dot] net.

—

A Brief Update On Ethnic Georgian Foreign Fighters In The Islamic State

By Bennett Clifford

Background

In 2015, the government of Georgia estimated that 41 of its citizens were active combatants in jihadist groups in Syria and Iraq, while other reports suggest that the contingent may have been as large as 100. The bulk of the foreign jihadist fighters from Georgia originated from the Pankisi Valley, an isolated set of villages in the north-east of the country that is renowned as a source of prominent foreign fighters, including the Islamic State (IS)’s deceased minister of war, Tarkhan Batirashvili (Umar al-Shishani). The majority population in the Pankisi Valley are Kists. Related closely to the Chechens of the North Caucasus, the Kists maintain distinct religious traditions, customs, folk laws (adat-tsesebi), and a unique dialect of the Chechen language.

Most of Georgia’s foreign fighters in Syria and Iraq are ethnic Kists from the Pankisi Valley, but the second largest demographic are ethnic Georgian Muslims. A database maintained by the author includes eight ethnic Georgians who successfully traveled to Syria and Iraq to join ISIS. Unlike in the Pankisi Valley, where foreign fighter recruitment is geographically consolidated, ethnic Georgian fighters come from various settlements and villages throughout the country. During Soviet rule in Georgia, particularly during its twilight years, ethnic Georgian Muslims living in the high mountainous communities of the south-western province of Adjara were resettled throughout the country due to a combination of ecological disasters and government planning policies. Most of the ethnic Georgian foreign fighters came from these “eco-migrant” settlements: in particular, the villages of Nasakirali and Zoti in the western province of Guria, and particular villages within the Tsalka municipality in the central Kvemo Kartli region.

This brief post covers the reported fates of three members of the ethnic Georgian foreign fighter contingent after the loss of IS territory in Syria and Iraq, revealing new information on their status and whereabouts. Perhaps most importantly, one of the major (and arguably, only) IS Georgian-language propagandists and the group’s standard-bearer, Tamaz Chaghalidze, is ostensibly alive and has returned to social media during the past few months, posting a barrage of new Georgian-language material. These posts glorify the martyred “heroes of the Islamic State,” offer justifications for IS’ losses in the sieges of Mosul and Raqqa, and provide insight on other Georgians in Syria and Iraq. One post, included in full with an English translation below, discusses the fates of two members of the group– Badri Iremadze and Murman Paichadze.

Who is Tamaz Chaghalidze?

Post from an autobiography on Tamaz Chaghalidze’s WordPress site. “Ahmad Jurji, also known as Tamaz Chaghalidze, was born on December 3, 1988 in the village of Zoti in Chokhatauri municipality.”

Tamaz Chaghalidze (kunya: Ahmad Jurji), largely unknown outside of Georgia, is directly responsible for the majority of IS propaganda in the Georgian language. Born in 1988 in the village of Zoti in the province of Guria, Chaghalidze left for the city of Batumi in Adjara in 2006, where he studied international economics at Shota Rustaveli State University. During his eight years in Batumi, he transitioned from participation as a political operative for a major Georgian party to an active figure in the local Islamist scene, and in 2014, he traveled to Syria to join the jihad. As an opening salvo in a flood of propaganda, shortly after his departure to Syria he published a video in August 2014 declaring his allegiance to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi and threatening Georgia for its mistreatment of Muslims.

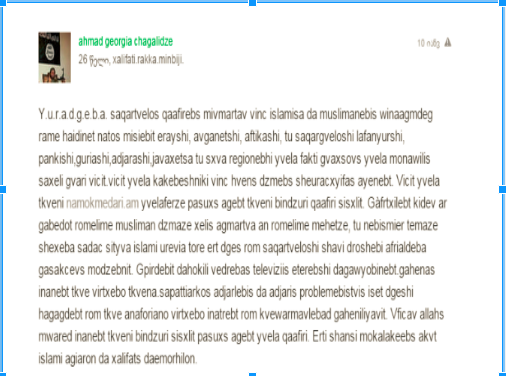

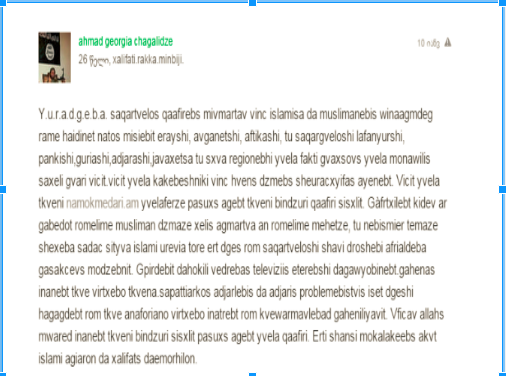

The video reached viral status in Georgia and resulted in the opening of an investigation by Georgia’s State Security Services into Chaghalidze’s threats against Georgia. Chaghalidze remained active online, utilizing a still-active Odnoklassiki profile which he opened before his departure to disseminate even more threats. Stylistically, Chaghalidze’s content errs towards self-promotion and directly appeals to ethnic Georgian Muslims, particularly eco-migrants. In many posts, he utilizes Adjaran dialect and slang, punctuating Salafi-jihadist religious teachings with invectives targeting members of the Georgian Orthodox Church, Georgian Muslim institutions, the Georgian armed forces, and others:

“Attention- to the kaafirs in Georgia who did anything against Islam and Muslims as part of NATO missions in Iraq, Afghanistan, Africa, or in Georgia itself in Lapanquri, Pankisi, Guria, Adjara, Javakheti or other regions. We know all your actions and you will pay for everything with your dirty kaafir blood. I warn you again- do not touch any Muslim brother or mosque or anything that concerns the name of Islam; otherwise, one day, when the black flags fly over Georgia, you will have nowhere to escape. You will beg on your knees, and they will show it on TV programs. You rats will regret the day you were created. We will cause so much trouble for the Patriarchate in Adjara that you robe-wearing rats will wish you were created as reptiles. I swear, by Allah, every kaafir will pay with their dirty blood. The one chance that civilians have is to accept Islam and pledge allegiance to the Caliphate.”

From 2015 until 2017, Chaghalidze maintained an extensive online presence from his base in Syria, running his own personal WordPress blog. In addition, he contributed to several other sites on WordPress, Facebook, Tumblr, Odnoklassiki, Myspace and Telegram entitled “Xalifat” [Caliphate] or “Daula” [The State], and ran multiple sock-puppet Facebook accounts. These pages disseminated efforts by Chaghalidze and other Georgian-speaking foreign fighters to translate official IS media products, such as the magazines Dabiq and Rumiyyah and the al-Bayan radio service, into their native tongue. As part of an ongoing investigation, the Georgian government repeatedly blocked the IP addresses of these pages, shutting off access in Georgia. Each time a page was shut down, another appeared in its place. Eventually, many of Chaghalidze’s efforts were consolidated into the group Bushra, which operates a still-active Facebook group, several Telegram channels, a justpaste.it account and uses a TutaNota email address.

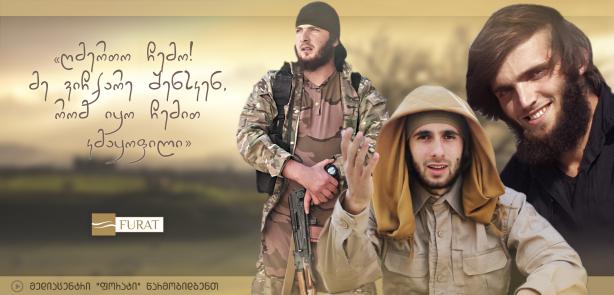

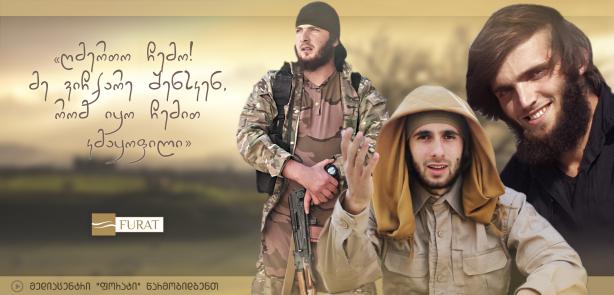

Posters for two official Islamic State releases in the Georgian language- “Message to the Georgian people” (2015, top) and “My God! I hasten towards you so that you would be satisfied with me” (2016, bottom)

Eventually, partially due to the success of Chaghalidze’s efforts in the unofficial realm, IS official media outlets published two releases in the Georgian language. In November 2015, IS’ al-Furat Media Foundation released “Gzavnili kartvel khalkhs” [Message to the Georgian People], its first full-length video in the Georgian language. The 12-minute video featured four ethnic Georgian fighters from Guria and Kvemo Kartli: Khvicha Gobadze (aka Abu Mariam al Jurji), Roin Paksadze, Mamuka Antadze, and Badri Iremadze. The second release, “Ghmerto chemo! Me vichkare shensken, rom iqo chemit kmaqopili” [My God! I hasten towards you so that you would be satisfied with me], was released in February 2016 and featured Chaghalidze, Iremadze, and the Kist fighter Mukhmad Baghakashvili eulogizing three slain Georgian IS fighters. In the second video, Chaghalidze appears in an IS police uniform—elsewhere, on his eponymous WordPress