English:

al-Qā’idah — “For the Family Of the Prisoner Warren Weinstein” (En)

Arabic:

al-Qā’idah — “For the Family Of the Prisoner Warren Weinstein”

______________

Category: United States

New article from Dr. Iyād Qunaybī: "Lesson From the Strikes Of America To [The Islamic] State"

____________

To inquire about a translation for this article for a fee email: [email protected]

New article from Shaykh Abū Basīr al-Ṭarṭūsī: "America and the Group [The Islamic] State 'Dā'ish'"

Click the following link for a safe PDF copy: Shaykh Abū Basīr al-Ṭarṭūsī — “America and the Group [The Islamic] State ‘Dā’ish'”

___________

To inquire about a translation for this article for a fee email: [email protected]

New video message from the Global Islamic Media Front: "The Story of an American Muhājir in al-Shām: A Special Meeting With the Mujāhid Shahīd Abū Hurayrah al-Amrīkī"

____________

al-Imārah Studio presents a new video message from the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan: "Exchange of Prisoners Between the Islamic Emirate and U.S. Government"

__________

To inquire about a translation for this video message for a fee email: [email protected]

New statement from the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan’s Mullā Muḥmmad ‘Umar: “Message Of Felicitation Regarding the Release of Jihādī Heads From 'Guantanamo Jail'"

I would like to congratulate from the core of my heart the whole Afghan nation, the devoted Mujahidin and the kith and kin of the prisoners on the auspicious occasion of this great achievement of the release of five distinguished Mujahidin heads from the ‘Guantanamo Jail’.

All praise is to Allah Almighty! Due to the benevolence of Allah Almighty, the enormous sacrifices of courageous Mujahidin and the statesmanship of the Political Bureau of the Islamic Emirate in Qatar, five prominent heads of the Islamic Emirate are soundly released from the ‘Guantanamo Jail’.

This huge and vivid triumph requires from all Mujahidin to offer thanks to the Benevolent Creator who accepted the sincere sacrifices of our Mujahid nation and managed the release of these five renowned Mujahidin from the enemy’s clutch.

The efforts and endeavors of all Mujahidin, leading council of the Islamic Emirate, the detainers and keepers of the American prisoner ‘Bergdahl’ and generally the whole nation which played a significant role in this colossal victory are appreciated and I beg even deeper divine help, guidance and favorable turn of circumstances for all of them.

I would like to thank his highness ‘Shaikh Tameem Bin Hamd Al-Thani’ the Amir of Qatar, for his sincere and friendly efforts and mediation in the release of these five prominent Mujahidin heads. I pray to Allah Almighty to reward him reciprocally in this world and in the world hereafter.

May Allah Almighty get, just like these five heads, all those oppressed prisoners released who are incarcerated in the path of liberating their country and serving their creed.

This huge accomplishment brings the glad tidings of liberation of the whole country and reassures us that our aspirations are on the verge of fulfillment, Insha-Allah.

And it is never hard for Allah Almighty.

Servant of Islam, Mulla Mohammad Omar Mujahid

03/07/1435 A.H. (Lunar)

11/03/1393 A.H. (Solar) 01/06/2014 A.D.

__________

New statement from the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan: "About the Release of Five Heads from 'Guantanamo Jail'"

We heartily congratulate the whole nation, Mujahidin of the Islamic Emirate, particularly the kith and kin of the released ones that five heads of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan namely Mulla Muhammad Fazal Akhund, Mulla Noorulla Noori, Mulla Khairulla Khairkhwa, Mulla Abdul Haq Waseeq and Moulavi Muhammad Nabi who had been incarcerated for the last thirteen years in ‘Guantanamo Jail’ are released due to the benevolence of Allah Almighty and the sacrifices of the heroic and courageous Mujahidin of the Islamic Emirate.

These five heads were released in the result of an indirect negotiation between the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan and the United States mediated by Qatari government. They will remain with their families inside Qatar and will lead a normal life.

To get the preceding five heads released, it is worth mentioning that the Islamic Emirate handed over the American soldier to the US who was captive with us approximately for the last five years.

These five heads of the Islamic Emirate were handed over on Saturday at 07:00 pm Afghanistan standard time to the delegation of Qatar who has been waiting there in ‘Guantanamo Bay’ for the previous three days. This delegation, including five heads of the Islamic Emirate, left Guantanamo at 10:00 pm and will arrive in Qatar today Sunday. They will be received and welcomed by the Political Bureau of the Islamic Emirate inside Qatar and members of the leading council of the Islamic Emirate. Similarly, the American prisoner ‘Bergdahl’ was handed over in the suburbs of ‘Khost’ province to the other side on Saturday at 07:00 pm Afghanistan standard time.

The Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan has been taking all possible measures since long to get all the Afghan prisoners released whether they are incarcerated inside the country or outside and to let them enjoy a free and peaceful life.

In the future too, the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan is determined to get all the Mujahidin prisoners released as soon as possible. In this regard, we expect all the legal and human rights societies particularly the United Nations to share and accelerate their efforts with Afghan people and the Islamic Emirate on the basis of human sympathy so that all the incarcerated people are freed and their basic legal and human rights are safeguarded and they could lead an independent and peaceful life of their own accord.

The Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan

___________

New statement from the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan: "Rejoinder Regarding Obama’s Recent Announcement Of the Extension Of the Occupation"

As Obama announced to keep nearly ten thousand troops inside Afghanistan till 2016 and protract the occupation, the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan strongly condemns this stance of the American politicians and considers it a clear violation of the religious, national and human rights of the freedom loving people of Afghanistan.

No human law allows anyone to violate the territorial boundaries of a sovereign country, usurp their political independence and bring them under military occupation. As the US authorities blatantly say to protract the occupation of Afghanistan till 2016, these expressions are very ignominious and they must be strongly condemned by those individuals, peoples and governments who are committed to sovereignty and freedom.

The Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan has explicitly manifested its stance on behalf of its pious masses about the US occupation i.e. even the presence of a single American soldier inside Afghanistan is unacceptable for our nation and masses; Jihad is obligatory against them and our people will continue their legitimate resistance and Jihad against them.

Prior to the invasion, we had told the Americans that they will not benefit from this felony rather it will increase their miseries but they did not pay any heed and now they are not only stuck into the longest and humiliating war of their history but also internationally their foes are increased; their military, political and economic majesty and supremacy are demolished; rather their decline and deterioration started from the start of this futile war.

A few years ago when the reins of power was transferred from Republicans to Democrats, we once again called upon the fire kindling US authorities to recompense the blunder of the previous government and if they insist on war, their casualties and humiliation will inevitably escalate but Barak Obama did quite the opposite. Instead of withdrawing his forces, he sent tens of thousands more troops to Afghanistan. The scope of resistance and struggle against the American occupation soared correspondingly with the increase of invading forces. The amount of casualties among the occupying forces escalated and eventually the American authorities were compelled to decide to quit from the battlefield.

We once again call upon the American officials that they are repeating the felony of their predecessors here; they are only wasting their time here; they are augmenting the miseries of our as well as their nations and eventually it is the American people who will suffer most from this futile war. The American authorities should presently take that decision which will have to eventually be taken by them two years later so that on one side, the sufferings of our people are brought to an end and on the other side, their casualties are not protracted too.

For the apprehension of the American authorities, we would like to elucidate that as a Muslim nation, Jihad is obligatory on us according to our beliefs till the end of occupation of our pious land by the infidel forces. The presence of armed infidel forces inside a Muslim land has no legitimacy and justification. Therefore the obligation of Jihad is not deferred with the quantitative decrease of the occupying forces rather it (Jihad) is as compulsory even against a single foreign soldier as it is obligatory against thousands of them.

Therefore, if the Americans want to relieve themselves as well as the Afghan masses from this futile Afghan war, they should completely withdraw their forces from Afghanistan as soon as possible.

The Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan

29/07/1435 A.H. (Lunar)

07/03/1393 A.H. (Solar) 28/05/2014 A.D.

__________

al-Malāḥim Media presents a new video message from al-Qā’idah in the Arabian Peninsula’s Jalāl al-Marqishī (Ḥamzah al-Zinjubārī): "Comment On the American Bombing Of Yemen"

UPDATE 6/16/14 9:37 PM: Here is an English translation of the below Arabic video message and transcription:

Click the following link for a safe PDF copy: Jalāl al-Marqishī (Ḥamzah al-Zinjubārī) — “Comment On the American Bombing Of Yemen” (En)

__________

—

UPDATE 5/27/14 9:15 PM: Here is an Arabic transcription of the below video message:

Click the following link for a safe PDF copy: Jalāl al-Marqishī (Ḥamzah al-Zinjubārī) — “Comment On the American Bombing Of Yemen” (Ar)

___________

—

___________

Hizballah Cavalcade: Bahrain’s Saraya al-Muqawama al-Sha’biya: Militants of the February 14 Youth Coalition

NOTE: For prior parts in the Hizballah Cavalcade series you can view an archive of it all here.

—

Bahrain’s Saraya al-Muqawama al-Sha’biya: Militants of the February 14 Youth Coalition

By Phillip Smyth

Figure 1: Saraya al-Muqawama al-Sha’biya’s logo.

Saraya al-Muqawama al-Sha’biya (The Popular Resistance Brigades or SMS), sometimes also called Saraya al-Muqawama (The Resistance Brigades), was listed by the government of Bahrain as a terrorist organization following the deadly March 3, 2014 bombing. The group, along with fellow militant group Saraya al-Ashtar, claimed responsibility for the attack. SMS has been operationally active and publishing its activities online since April 2012. Importantly, Saraya al-Muqawama al-Sha’biya does not hide that they are affiliated with one of the main anti-government protest groups, the February 14 Youth Coalition (which was also listed as a terrorist organization by the government of Bahrain). This is hardly a minor connection, since, both the February 14 Youth Coalition and SMS have also distributed images sharing one another’s logos, organized events (such as protests) together, and share a similar narrative. Other militant groups—namely Saraya al-Ashtar and Saraya al-Mukhtar—have only vaguely claimed to represent links to protestors, let alone main protest organizations.

In June 2013, the Bahraini government accused the February 14 Youth Coalition of having a “spiritual leader” based in Karbala, Iraq and of, “frequently travel[ing] between Iran, Iraq and Lebanon to obtain financial and moral support as well as weapons training.” However, Bahraini authorities provided little substantiating evidence dealing with claims of Iranian or Iranian proxy involvement. Nevertheless, according to Iranian reports, February 14 Youth Coalition representatives have thanked Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei for his comments supportive of their activities. Iranian media has also expressed their support for the “revolutionary activities” of the Bahraini group. Despite these pronouncements, the actual relationship between Iran and the February 14 Youth Coalition, particularly dealing with any attempts at training or equipping militant elements attached to the organization, is still unknown.

Figure 2: Both the February 14 Youth Coalition and Saraya al-Muqawama al-Sha’biya’s logos on a promotional image released onto multiple February 14 Youth Coalition pages.

Figure 3: SMS supporters carry the group’s flag during a march.

Figure 4: SMS and February 14 Youth Coalition supporters march together and carry February 14 Youth Coalition flags.

Initially, the February 14 Youth Coalition did not embrace violence. However, after publishing a series of “warnings” to the Bahraini government, Gulf Arab states (namely, Saudi Arabia and the UAE) which have deployed forces to Bahrain, and foreigners recruited into the Bahrain’s internal security forces (often referred to by the group and other Bahraini militants as, “mercenaries”), the coalition issued communiques demonstrating they would choose a more militant path of “resistance.” In a January 27, 2012 English-language statement made by a February 14 Youth Coalition affiliated page, the group issued a statement reading:

“We have so far preserved our right to use force for self-defense, hoping that would make you hesitant from attacking peaceful protestors, women and children. However, common sense and human logic do not seem to work on you…Our people have decided to bring an end to the illegitimate regime…We shall take no responsibility for whatever might happen to the mercenaries after this final warning.”

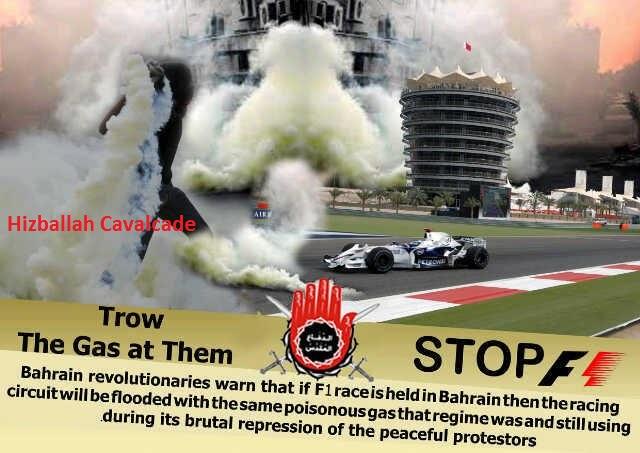

Three months after this announcement, SMS pushed for a response to the holding of the controversial 2012 Bahrain Grand Prix Formula 1 race. The group released images urging protestors to throw the gas (the group claimed it was poisonous) used by Bahraini police at the race cars. However, no armed action was taken against the race by SMS. It is likely that in such an early stage of development and combined with Bahraini government crackdowns, the group was unable to act.

Figure 5: One of SMS’s English language posters calling for action against the 2012 Grand Prix race.

Narrative Structure

SMS considers its fighters to be “jihadists,” refer to their attacks as “jihadist operations,” and believe they are fighting a “jihad against the infidel Khalifas [Bahrain’s ruling royal family].” While the message of jihad is repeated in many SMS statements, these statements do not share the same level of more complicated religious and ideological messaging found with other non-Bahraini Shia jihadist elements.

SMS also lacks a specific goal for what type of government will rule in Bahrain following a theoretical collapse of the currently ruling Khalifa royal family. Still, this has not stopped the group from constructing complex narratives via militant activity for their enemies.

Following Saraya al-Ashtar’s and SMS’s claim of responsibility for the March 3, 2014 bombing (which killed two Bahraini police officers and a police officer sent by the United Arab Emirates [UAE] to Bahrain), SMS used the opportunity to criticize government claims that forces of the Peninsula Shield Force were being used in conjunction with local Bahraini police forces to counter protests and riots.

Sent to Bahrain in 2011, the Peninsula Shield Force included hundreds from the Saudi military and the UAE’s police force. Officially, these units claimed they were not involved in internal matters in Bahrain and were only interested in securing strategic bases and locations from “external influence.” Regardless, the death of a UAE police officer attached to Bahraini police served as a propaganda coup for SMS.

The timing of the SMS’s bombing claim and messages which proceeded it also fit into a broader message dealing with the Peninsula Shield Force and particularly Saudi Arabia. SMS has demonstrated a specific ire for the Saudis. The organization’s communiques have called Saudi Arabia the “usurper of land,” “occupiers,” and have stated their operations are to “purge the land of its Saudi and Khalifa occupiers.”

In part, this may tie back to February 14 Youth Coalition links to Saudi Shia activists. Researcher Fredric M. Wehrey noted that an “important attribute of the February 14 Youth Coalition is its strong affinity with Shi’a activists in neighboring Saudi Arabia.” Wehrey went on to explain how coordinated protests were conducted by Bahraini and Saudi groups out of solidarity. The February 14 Youth Coalition’s and SMS’s links to the Saudi Shia is also important when viewed in context with announcements by fellow militant organization, Saraya al-Mukhtar. Saraya al-Mukhtar has issued a number of announcements saying they share the cause of the “people of the [Saudi] Eastern Region” –an area heavily populated by Saudi Shia. The shared narrative may demonstrate deeper links between Saraya al-Mukhtar, SMS, and the February 14 Youth Coalition.

Figure 6: A poster released by the February 14 Youth Coalition asking, “Who are the terrorists?” The photo shows Saudi forces crossing the King Fahd Causeway which links Bahrain to Saudi Arabia.

As part of the view casting the Saudis as foreign occupiers, activists from SMS and the February 14 Youth Coalition have drawn parallels between Israel and Saudi Arabia; accusing both counties of using the same techniques of occupation. Prior to a series of March 2014 protests against “Saudi occupation”, the February 14 Youth Coalition and SMS circulated images attempting to link Saudi Arabia and Israel as fellow occupying states. This also extended into the realm of February 14 Youth Coalition partisans attempting to directly link the causes of Palestinian and Bahraini demonstrators.

Figure 7: The Israeli flag flies behind Jerusalem’s Dome of the Rock (left) while a bulldozer is shown destroying the 400 year old Amir Mohammed Braighi Mosque with a Saudi flag behind it (right). The latter incident occurred in 2011 along with the Bahraini government destruction of other Shia mosques. This picture was used as a tool to organize activists for protests and events against the “Saudi occupation.”

Figure 8: A poster showing a Bahraini protester (with February 14 Youth Coalition) and a Palestinian activist. The former looks to the now demolished Pearl Roundabout statue, the latter looks to the Dome of the Rock. The picture attempts to show a unity of purpose and cause between Palestinian and Bahraini demonstrators.

Symbols of the “Popular Resistance”

Figure 9: SMS protesters at a February 14 Youth Coalition event demonstrating against “The Saudi Occupation.”

Shia symbolism is heavily featured in the group’s logo. The most prominent image is the symbolic hand of Shia leader Abbas Ibn Ali; son of the first Shia imam and loyal aid and military leader for the third Shia imam, Husayn ibn Ali. Serving as Husayn’s flag bearer during the historic Battle of Karbala, Abbas’s hand was cut off by one of the forces of Yazid, the reviled leader of the Umayyads, as Abbas went alone to collect water for Husayn’s dehydrated camp. Abbas went on to fight singlehandedly until his other arm was cut off by sword strikes from Yazid’s forces and was then killed. Abbas’s loyalty and steadfastness until being cut down remains an important message for many Shia Muslims.

Another unique feature from the logo is that “The Sacred Defense” is written within the symbolic hand of Abbas. This helps convey that the group’s conflict with the government is viewed as both a defensive and religiously justified action. Intriguingly, the Shia jihad in Syria and the Iran-Iraq War (1980-1988) have (by Shia actors) both been described as “The Sacred Defense.”

Behind the