NOTE: For prior parts in The Archivist series you can view an archive of it all here. And for his older series see: Musings of an Iraqi Brasenostril on Jihad.

—

Unseen Documents from the Islamic State’s Diwan al-Rikaz

By Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi

The Diwan al-Rikaz (Department of Precious Resources) is one of the Islamic State’s [IS] bureaucratic wings that have emerged since the announcement of the Caliphate on 29 June 2014. Literally, al-Rikaz refers to anything that can be extracted from the ground. In that regard, the Diwan has a number of sub-divisions, most notably including oil and gas as well as antiquities. Mining and trading of minerals also fall under the Diwan al-Rikaz’s authority. Previously I have covered some specimen documents from the Diwan al-Rikaz, such as the leasing of gasoline stations in Mosul, oil and gas distributions to the local population, oil and gas sale receipts and permission for excavating antiquities.

As with other IS departments, co-optation of existing structures is key as part of the emphasis on authorization and oversight of activity, particularly when it comes to oil and gas resources. Compare, for instance, with the Diwan al-Siha (Health Department) requirement for new pharmacies and clinics to have its stamp of approval.

Though some skilled engineers may exist among the ranks of the muhajireen who join IS, IS will in the main part have to rely on the personnel and infrastructure already there for the oil and gas industries: a case-in-point being the Diwan al-Rikaz order for employees of the gasworks in Ramadi to register and undertake regular duties a few weeks after the city fell to IS. Co-optation might entail having to pay additional fees to convince personnel to operate under IS authority. Further, problems may arise with inability to repair and update infrastructure, significantly reducing potential for extraction of resources and production for commercial use.

As these points are often not taken into consideration, the contribution of oil and gas revenues to IS finances has been overstated- an observation corroborated by the leaked financial records from Deir az-Zor province, IS’ richest oil and gas holdings. Further, conventional wisdom tends to place too much emphasis on smuggling to the outside world- where even more cuts to final profits occur in the form of middlemen- at the expense of meeting domestic needs for oil and gas.

The IS emphasis on regulation also applies to other sub-divisions of the Diwan al-Rikaz, as illustrated in the documents from the Abu Sayyaf raid. For example, in one of the documents, the General Supervisory Committee stresses that only those with permits issued by the Diwan al-Rikaz can excavate antiquities. An overlooked aspect of the regulation is that authorized dealings in antiquities generally seem to be required to be confined within IS provincial boundaries (or at least the boundaries of IS territory).

This makes sense when one considers what form revenue for IS from the sale of antiquities primarily appears to take: namely, a portion of the money a licensed excavator gains from the direct sale of antiquities is to be paid in taxation to the Diwan al-Rikaz. Such a picture is contrary to the popular conception of a pervasive, authorized chain of smuggling onto the international black market, which, as is the case with smuggled oil, would involve middlemen taking considerable slices of the proceeds and thus likely prove less profitable to IS.

Indeed, after Palmyra fell into IS hands, the Diwan al-Khidamat (services department) issued a notification prohibiting moving of and dealing in artifacts found in the town of Palmyra for outside the borders of Wilayat Homs. Similarly, note some receipts recovered from the Abu Sayyaf raid refer to antiquities sold in WIlayat al-Kheir (Deir az-Zor province). Likewise, a friend in Azaz tells me that IS has arrested and imprisoned people who have tried to smuggle statues and other artifacts into rebel-held areas. None of this means that there has been no smuggling of antiquities and the like from IS-held territories onto the international black market, or that certain corrupt IS officials are not involved in such a process. Rather, the point is that the revenue for IS mainly seems to come from taxation after direct sale following excavation.

Below are some more unseen specimen documents I have obtained to shed further light on the operations of the Diwan al-Rikaz. All of them illustrate the central theme of regulation I have noted above. Specimen B in particular shows an aim to stamp out smuggling through the northern borders to Turkey. As shown in the Deir az-Zor province financial records, confiscations play an important role in IS revenue, and confiscation of resources and goods moved without authorization of the Diwan al-Rikaz likely generates considerable revenue as well within that framework. Two names that recur in these documents- Abu al-Layth al-Furati and Abu Omar al-Falastini- appear to be heads of the Diwan al-Rikaz in Homs and Aleppo provinces respectively.

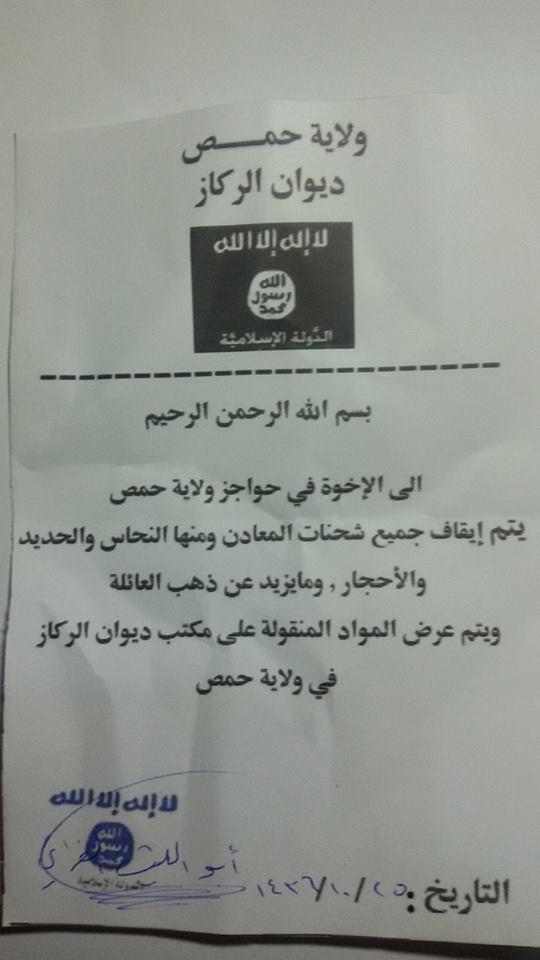

Specimen A

Islamic State

Wilayat Homs

Diwan al-Rikaz

In the name of God, the Compassionate, the Merciful

To the brothers in the checkpoints of Wilayat Homs

One must stop all cargoes of minerals, including copper, iron, [precious] stones and what exceeds family gold. The transferred goods are to be sent for examination to the office of the Diwan al-Rikaz in Wilayat Homs.

Islamic State

Abu al-Layth al-Furati

Date: 25/10/1436 AH [10 August 2015]

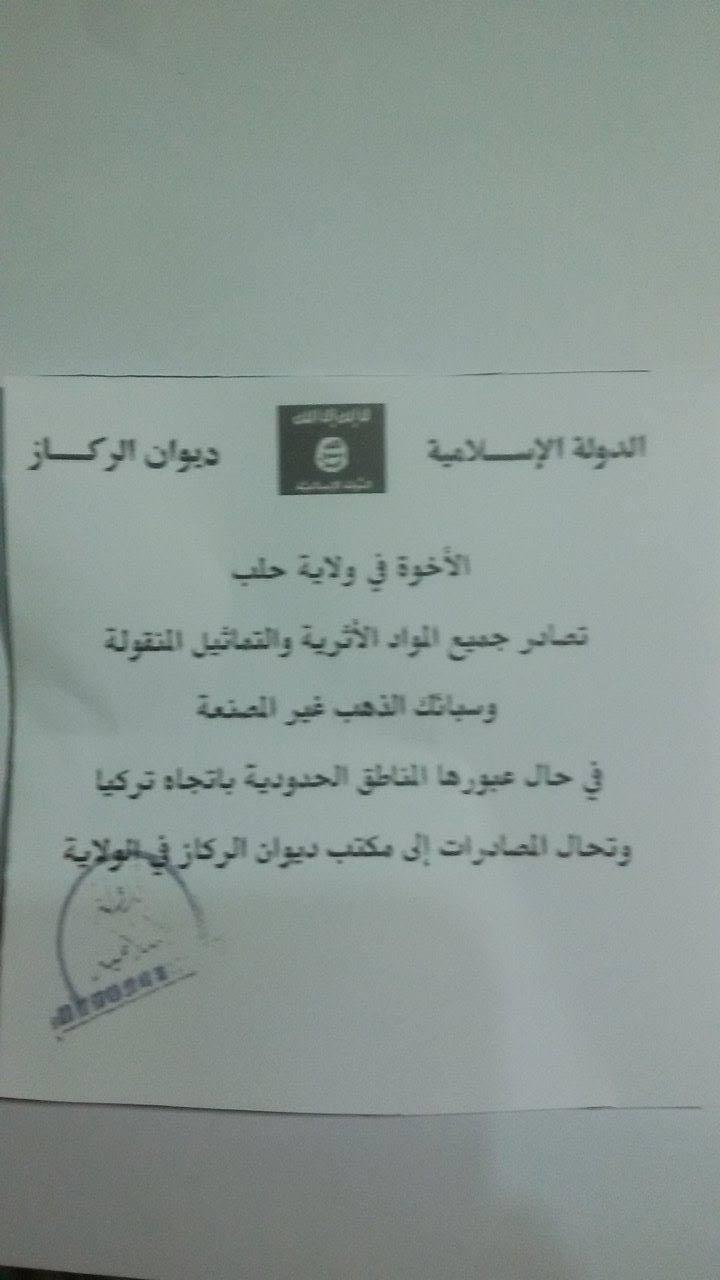

Specimen B

Islamic State

Diwan al-Rikaz

Brothers in Wilayat Halab

All antiquities, moved statues and unprocessed gold bullions are to be confiscated in the event that they are being passed through the border areas towards Turkey. And the confiscated goods are to be referred to the Diwan al-Rikaz office in the wilaya.

Islamic State

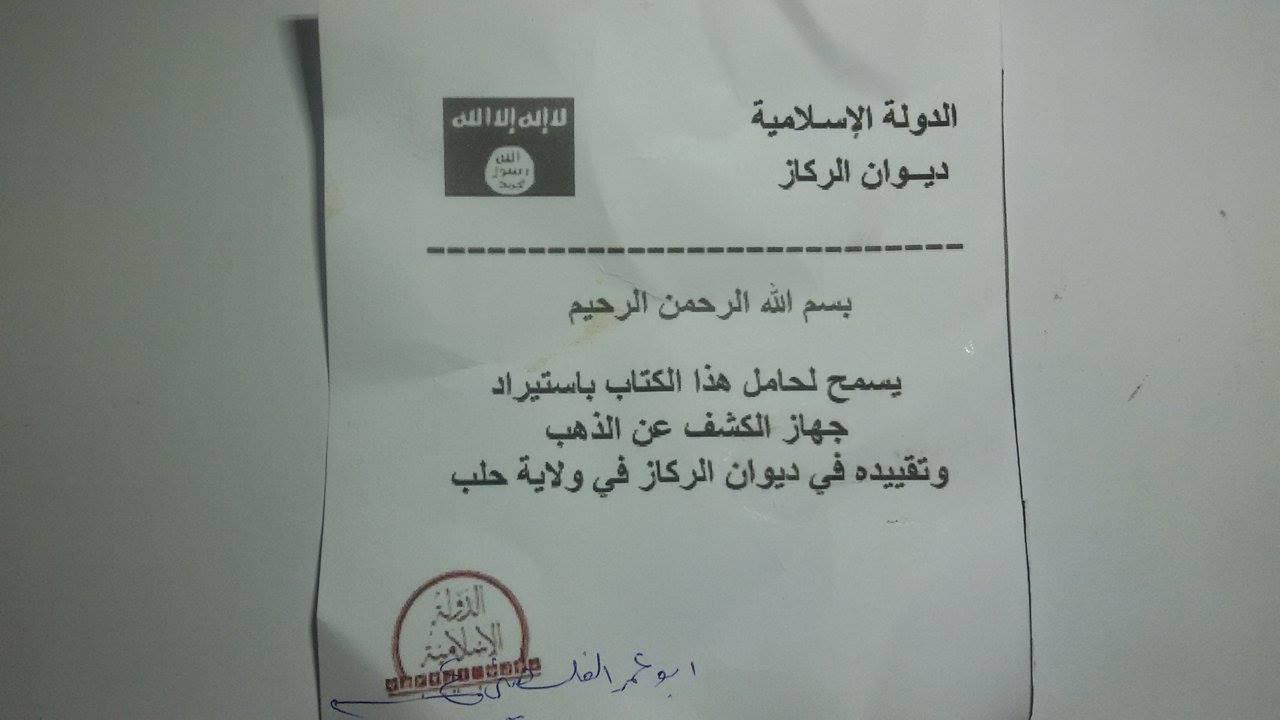

Specimen C

Islamic State

Diwan al-Rikaz

In the name of God, the Compassionate, the Merciful

The bearer of this document is permitted to procure equipment to search for gold and register it in the Diwan al-Rikaz in Wilayat Halab.

Islamic State

Abu Omar al-Falastini

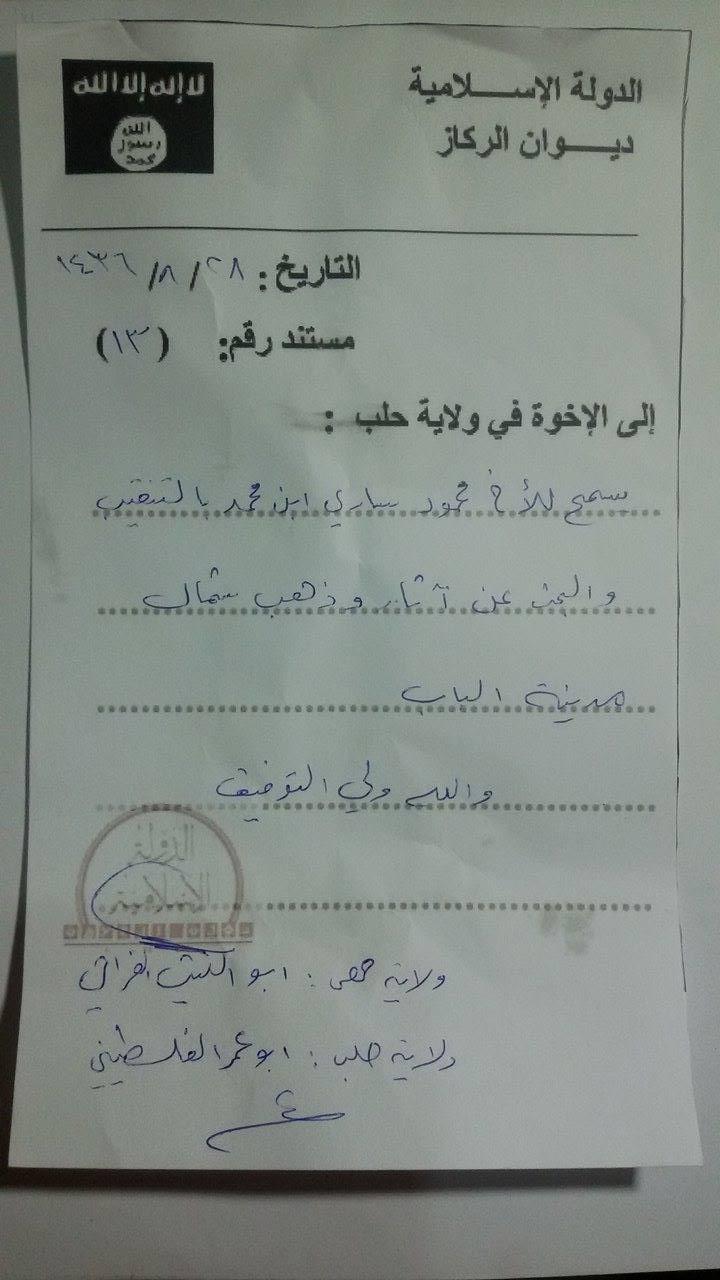

Specimen D

Islamic State

Diwan al-Rikaz

Date: 28/8/1436 AH [15 June 2015]

Case no. 13

To the brothers in Wilayat Halab

The brother Mahmoud Sari ibn Muhammad has been permitted to excavate and search for antiquities and gold north of the town of al-Bab. And God is the guarantor of success.

Islamic State

Wilayat Homs: Abu al-Layth al-Furati

Wilayat Halab: Abu Omar al-Falastini

Category: The Archivist

The Archivist: Unseen Islamic State Financial Accounts for Deir az-Zor Province

NOTE: For prior parts in The Archivist series you can view an archive of it all here. And for his older series see: Musings of an Iraqi Brasenostril on Jihad.

—

Unseen Islamic State Financial Accounts for Deir az-Zor Province

By Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi

The question of where the Islamic State [IS] acquires its funding has been a subject of much discussion. Though ideological partisans often see a private Gulf Arab funding hand behind IS, the general consensus now seems to accept that IS is not dependent on foreign donors in any meaningful way, and thus largely acquires its revenues from resources within the territories it operates, including taxation, sales of oil and gas, antiquities and the like. Thus, the majority of the debate now focuses on trying to determine the relative importance of each of these sources of revenue.

A number of analyses have been produced relying on local sources within Iraq and Syria, and in this regard I highly recommend Die Zeit’s investigation from December 2014, the fruit of a team of researchers including my colleague Yassin Musharbash.

However, a deficiency in all the work thus far on IS finances is a lack of statistics from IS itself on income and expenditures, and so a degree of guesswork in estimating has always been involved. The exclusive documents that will be presented below- obtained from IS’ Diwan Bayt al-Mal (financial ministry) in eastern Syria’s Deir az-Zor province (Wilayat al-Kheir)- provide a remedy in giving a first time view of IS budgets by its own account for the month of Rabi’ al-Awal 1436 AH (c. 23 December 2014-22 January 2015).

For context, Deir az-Zor province has been almost entirely under the control of IS since July 2014, while a regime presence still holds out in parts of Deir az-Zor city and at a military airport. In defeating the rebels in Deir az-Zor province, IS has gained a monopoly on oil and gas resources in the province. The province’s long-standing importance to the oil and gas sector of the Syrian economy is well-known, and it undoubtedly constitutes the largest pool of oil and gas resources in Syria that IS has been able to exploit.

As part of its narrative of ‘breaking the borders’ between Syria and Iraq, IS created a ‘Euphrates Province’ that spans eastern Deir az-Zor province and western Anbar province, including the districts of Albukamal in Syria and al-Qa’im, Rawa and Anah in Iraq.

Figures in the documents help us to quantify IS financing. From IS’ richest province in fossil fuels, revenues and expenditures for the province come in the form of millions of dollars on a monthly basis, not tens or hundreds of millions. Further, despite the significant holdings of oil and gas resources, these sources of revenue by no means constitute the majority of IS’ income in the province. Statistically, revenue streams for the province can be divided as follows using the data from the documents:

| Source | Percentage of Revenue |

| Oil & Gas | 27.7% |

| Electricity | 3.9% |

| Taxes | 23.7% |

| Confiscations | 44.7% |

As can be seen, a plurality of the income actually comes from confiscations of property and money. This may take place for a number of reasons: e.g. residents who fled their homes, violations of IS regulations and illicit smuggling of goods, particularly forbidden items like cigarettes and alcohol. Movement across border areas is important in this regard when combined also with transit fees for legitimate travel and transportation of goods.

Meanwhile, IS’ expenditures primarily go towards military upkeep in the form of expenditures for bases and paying fighters’ salaries. Conspicuously absent from the expenditures are accounts for salaries of workers officially under the authority of the Diwan al-Ta’aleem (education). The reason for this is that the IS process of revamping the education system in accordance with its ideology required the closing of many schools in this period to subject teachers and staff to ‘repentance’ and Shari’a lessons, while the regime continued to pay salaries though under strict conditions for the recipients to come in person to the relevant places stipulated by the regime. Note that the Islamic Police comes under the Diwan al-Hisba working closely with IS’ judiciary department (Diwan al-Qada wa al-Mazalim), and both these diwans play key roles in confiscations of goods and property. Here is the breakdown of expenditures by percentage.

| Expenditure | Percentage of Expenditure |

| Expenditures for bases | 19.8% |

| Fighters’ salaries | 43.6% |

| Media | 2.8% |

| Islamic Police | 10.4% |

| Diwan al-Khidamat (Services Department) | 17.7% |

| Diwan Bayt al-Mal: aid sums | 5.7% |

Some more points of analysis to consider:

– Popular conceptions of IS income need to have a more sober and realistic perspective on the role oil and gas revenues. Daily revenues from the oil wells here (total divided by 30) yield on average $66,433. If this is the average revenue from IS’ best oil holdings in Syria and one engages in reasonable extrapolation, then one will come nowhere near the total figure of $3 million a day for IS in oil sales that was widely touted in the media in summer 2014, even when making allowances for subsequent damage to infrastructure from coalition airstrikes. A sounder estimate would put such income at no more than 5-10% of that figure.

– On a related historical note, one should dismiss accounts that portray IS’ predecessors as being suddenly enriched from eastern Syrian oilfields and antiquities beginning in late 2012, based on hearsay about alleged computer flash sticks revealing IS finances and off-base regarding the dynamics of control of eastern Syrian oil over the course of the Syrian civil war (pace the Guardian report, IS’ predecessor ISIS did not exist in late 2012, let alone ‘commandeer’ eastern Syrian oilfields).

– The sale of antiquities under the authority of the antiquities subdivision of the Diwan al-Rikaz is not explicitly mentioned in the accounts here, but it is most likely included within taxation as part of the IS bureaucratic structure. Documents captured from the Abu Sayyaf raid by U.S. forces appear to show a 20% tax to be paid on antiquities sold in Deir az-Zor province. Two of the individual transactions presented from December 2014 illustrate tax payments of more than $10,000, while the third constitutes a little over $1000.

– Despite IS’ propaganda on ‘breaking the borders’ and the creation of ‘Euphrates Province’, the inclusion of Albukamal within Deir az-Zor province financial data and transactions is an example of how IS still deals in prior administrative boundaries. Compare with a previous July 2015 document I published from Wilayat al-Kheir’s Diwan al-Khidamat ordering for an Abu Dujana al-Libi to be paid $100,000 for a road project between Albukamal and al-Qa’im. Other administrative documents from ‘Euphrates Province’ indicate that IS administration rarely seems to deal with the territory as a united entity, but rather by its Syrian and Iraqi halves. This is so even as travel within ‘Euphrates Province’ is relatively easy, as a friend of mine from Rawa now works in Albukamal, and residents on both sides of the Iraq-Syria border regularly cross both ways for business, market shopping etc.

– Ultimately, the most vital IS revenues depend on the continued existence of its bureaucratic structure within the territories it controls, and there is little one can do to disrupt that short of destroying that structure militarily. The suggested siege-like strategy to trigger a collapse from within is impossible to realize in the current circumstances, as one cannot wholly isolate IS territory from interactions with the outside world, and so cash flows will continue. The Iraqi government’s decision to cut off direct salary payments to workers in IS-held areas will certainly help reduce IS taxation revenues, but it was not the sole avenue for cash flow, and though hardships for residents will increase, IS’ rigid security apparatus is still highly capable of suppressing major revolt.

Below are the documents with translation.

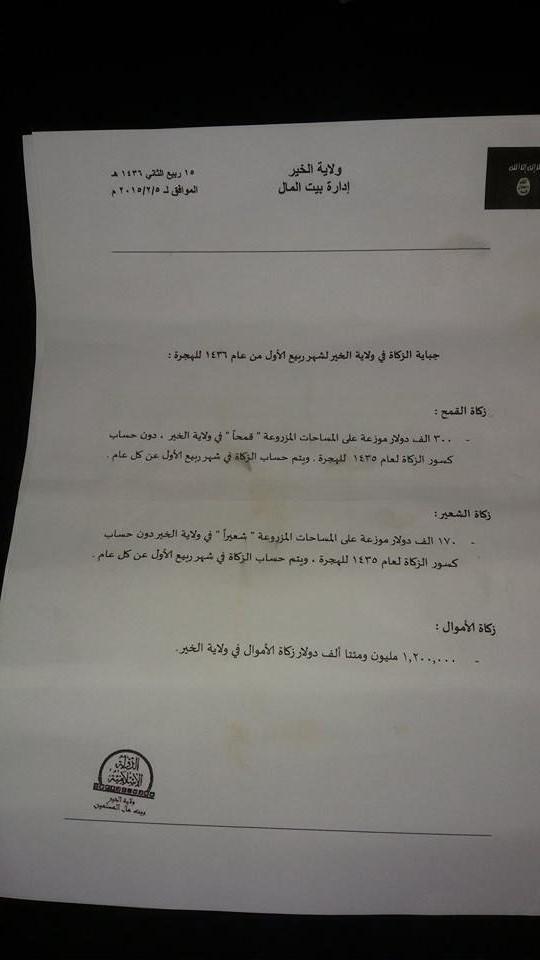

Islamic State

Wilayat al-Kheir

Diwan Bayt al-Mal

Bayt al-Mal Administration

15 Rabi’ al-Thani 1436 AH

5 February 2015

Rough draft of the operation of the management of wealth project.

Bayt al-Mal in Wilayat al-Kheir

Copy to the Diwan al-Wilaya [governor’s office]

Copy to the Diwan al-Hisba [checks for potential irregularities in the records etc.]

Uncirculated

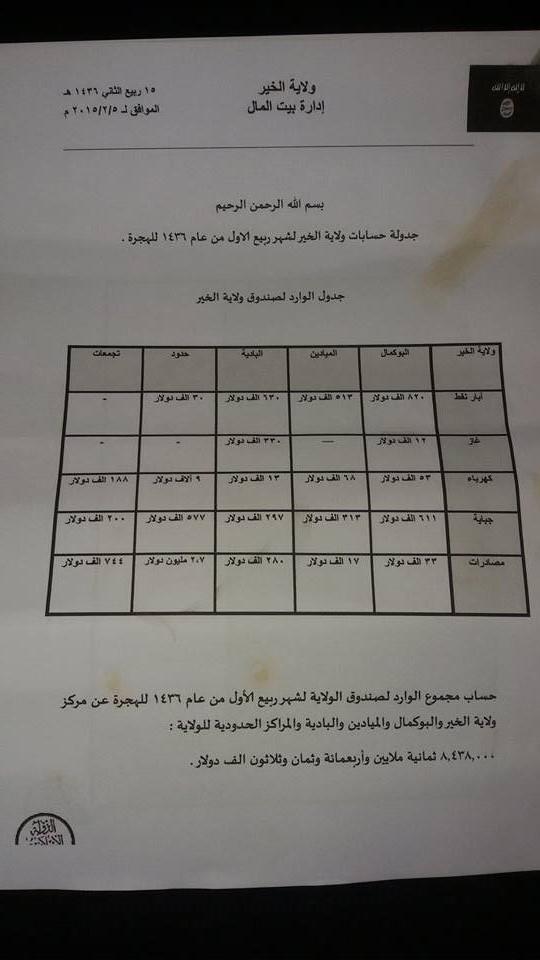

In the name of God, the Compassionate, the Merciful

Table of accounts for Wilayat al-Kheir for the month of Rabi’ al-Awal of the year 1436 AH

Table for income to the treasury of Wilayat al-Kheir.

| Wilayat al-Kheir | Albukamal | Al-Mayadeen | Al-Badiya | Borders | Tajammu’at [Deir az-Zor area residential districts] |

| Oil wells | $820,000 | $513,000 | $630,000 | $30,000 | |

| Gas | $12,000 | $330,000 | |||

| Electricity | $53,000 | $68,000 | $13,000 | $9,000 | $188,000 |

| Taxes | $611,000 | $313,000 | $297,000 | $577,000 | $200,000 |

| Confiscations | $33,000 | $17,000 | $280,000 | $2,700,000 | $744,000 |

Total accounting of income for the treasury of the Wilaya for the month of Rabi’ al-Awal of the year 1436 AH from the centre of Wilayat al-Kheir, Albukamal, al-Mayadeen, al-Badiya and the border centres for the Wilaya is $8,438,000.

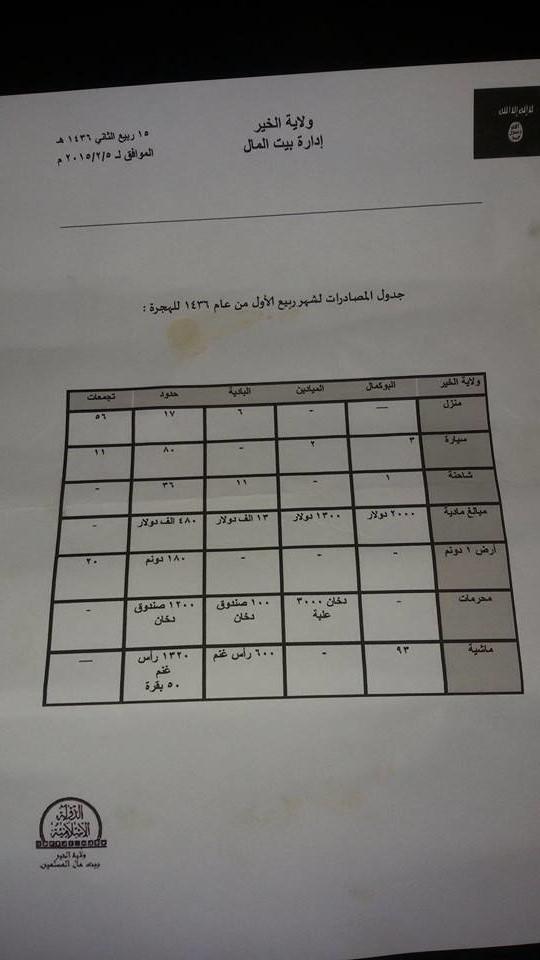

Table of confiscations for the month of Rabi’ al-Awal of the year 1436 AH:

| Wilayat al-Kheir | Albukamal | Al-Mayadeen | Al-Badiya | Borders | Tajammu’at |

| House | 6 | 17 | 56 | ||

| Car | 3 | 2 | 80 | 11 | |

| Truck | 1 | 11 | 36 | ||

| Material sums | $2000 | $1300 | $13,000 | $480,000 | |

| Land (in dunams) |

180 dunams | 20 | |||

| Forbidden items | Cigarettes: 3000 packs | 100 cases of cigarettes | 1200 cases of cigarettes | ||

| Livestock | 93 | 600 head of sheep | 1320 head of sheep, 50 cows |

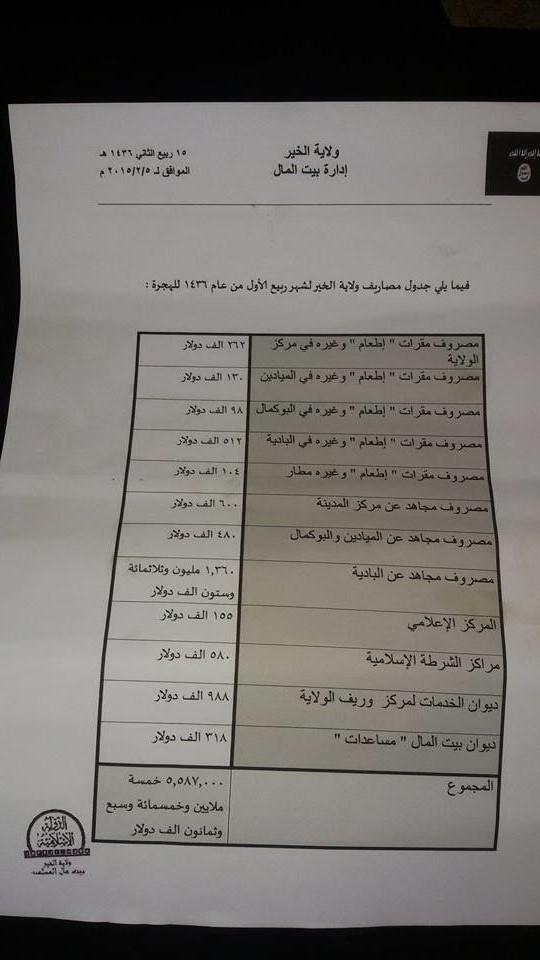

In what follows is a table of expenditures for Wilayat al-Kheir for the month of Rabi’ al-Awal of the year 1436 AH:

| Expenditure for the bases: “Provision of food” etc. in the centre of the wilaya | $262,000 |

| Expenditure for the bases: “Provision of food” etc. in al-Mayadeen | $130,000 |

| Expenditure for the bases: “Provision of food” etc. in Albukamal | $98,000 |

| Expenditure for the bases: “Provision of food” etc. in the Badiya | $512,000 |

| Expenditure for the bases: “Provision of food” etc.: airport | $104,000 |

| Mujahid allowance [monthly salaries for fighters] from the city centre | $600,000 |

| Mujahid allowance from al-Mayadeen and Albukamal | $480,000 |

| Mujahid allowance from the Badiya | $1,360,000 |

| Media centre | $155,000 |

| Islamic Police centres | $580,000 |

| Diwan al-Khidamat for the centre and countryside of the wilaya | $988,000 |

| Diwan Bayt al-Mal: aid sums | $318,000 |

| Total | $5,587,000 |

Zakat taxes in Wilayat al-Kheir for the month of Rabi’ al-Awal of the year 1436 AH:

Zakat on wheat:

. $300,000 distributed upon [i.e. imposed as zakat taxation on] the cultivated lands in ‘wheat’ in Wilayat al-Kheir, without taking into account the kusur of the zakat [zakat that could not be paid] for the year 1435 AH, and accounting of zakat will be accomplished in the month of Rabi’ al-Awal every year.

Zakat on barley:

. $170,000 distributed upon the cultivated land in ‘barley’ in Wilayat al-Kheir,

The Archivist: Unseen Islamic State Fatwas on Jihad and Sabaya

NOTE: For prior parts in The Archivist series you can view an archive of it all here. And for his older series see: Musings of an Iraqi Brasenostril on Jihad.

—

Unseen Islamic State Fatwas on Jihad and Sabaya

By Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi

Islamic State [IS] fatwas are the product of the Diwan al-Eftaa’ wa al-Buhuth (Fatwa Issuing and Investigation Department), which is also responsible for the production of Islamic State training camp textbooks such as the basic Muqarrar fi al-Tawhid (“Course in Tawheed”). The Diwan al-Eftaa’ wa al-Buhuth was founded following the declaration of the Caliphate and is illustrative of the wider trend of more complex IS government organization since the Caliphate declaration embodied in the diwans, ostensibly functioning as a conventional central government with provincial and local branches of administration departments.

The main centre for the Diwan al-Eftaa’ wa al-Buhuth is the de facto IS Syrian capital of Raqqa. This should not be surprising considering the leading role in this diwan played by Bahraini cleric Turki Binali, who most recently appeared in public IS propaganda at Eid al-Fitr prayers in the al-Nur mosque in Raqqa. At the diwan’s centre in Raqqa, new fatwas are devised, printed and distributed, with distributions also occurring in the de facto IS Iraqi capital of Mosul.

The fatwas presented below- previously unseen- come from the latest printing of 50 IS fatwas. The numbering of these fatwas should therefore not be confused with earlier fatwas collected by me and Cole Bunzel, which are now much harder to come by even within IS territory. Indeed, the fatwas differ from other IS publications such as the pamphlets of the Diwan al-Da’wa wa al-Masajid in that the latter are intended for distribution to the masses through local offices, ‘media points’ and the like.

In contrast, the fatwas- particularly pertaining to the conduct of war- are most relevant for those formally affiliated with the ranks of IS. As Bunzel notes, prior to the 32 fatwas uploaded by a low profile IS account that called itself Abu Umar al-Masri, the only publicly known fatwa was the one justifying the burning alive of Jordanian pilot Muadh al-Kasesbeh that circulated alongside the release of the video, widely circulated and intended to illustrate the principle of mumathala (retaliation in the literal sense of an ‘eye for an eye’). Besides these documents, I know of only two other fatwas that came to public light at random: one on whether one could eat meats imported from Turkey, and another on whether one could shorten prayer or break the fast in Ramadan while making hijra to Dar al-Islam (Specimens 3K and 3L in my main archive of documents).

Below is each fatwa presented and translated, with notes where applicable.

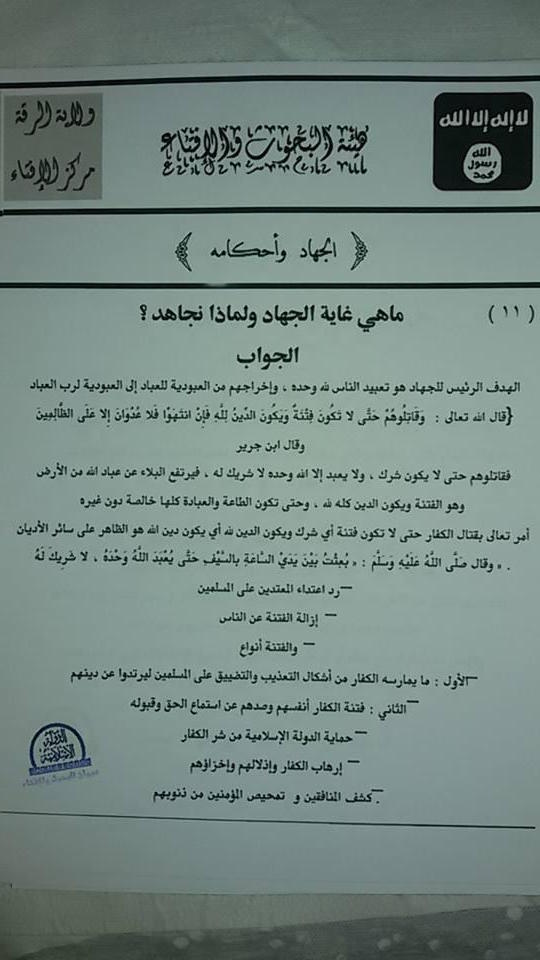

Specimen A: Purpose of Jihad

al-Buhuth and al-Eftaa’ Committee

Wilayat al-Raqqa

al-Eftaa’ Centre

Jihad and its rulings

No. 11

Q: What is the goal of jihad and why do we wage jihad?

A: The principle aim of jihad is to make people worship God alone, and move people away from servitude to men towards servitude to the Lord of men. God Almighty has said: “And fight them until there is no more fitna and religion is for God, and if they cease, there is no enmity except upon the wrongdoers” [Qur’an 2:193].

And Ibn Jubayr said: “So fight them until there is no shirk, and only God alone is worshipped with no partner for Him, and thus affliction is removed from the servants of God from the Earth (i.e. fitna) and religion is wholly for God, and obedience and servitude will be wholly pure without any besides Him.”

The Almighty has ordered to fight the kuffar until there is no more fitna- i.e. shirk- and religion is for God- i.e. it is the religion of God, prevailing over the other religions. And SAWS said: “I was sent before the Hour with the sword so that God alone should be worshipped, with no partner for Him.

– Repulsing the aggressors against the Muslims.

– Removing fitna from the people.

– And the fitna is of multiple types:

– First: what the disbelievers deal in regarding forms of torture and stranglehold on the Muslims so that they apostasise from their religion.

– Second: fitna of the disbelievers themselves and their refusal to listen to and accept the truth.

– Protecting the Islamic State from the evil of the disbelievers.

– Terrorising the disbelievers, subjugating them and humiliating them.

– Exposing the munafiqeen [hypocrites] and testing the believers regarding their sins.

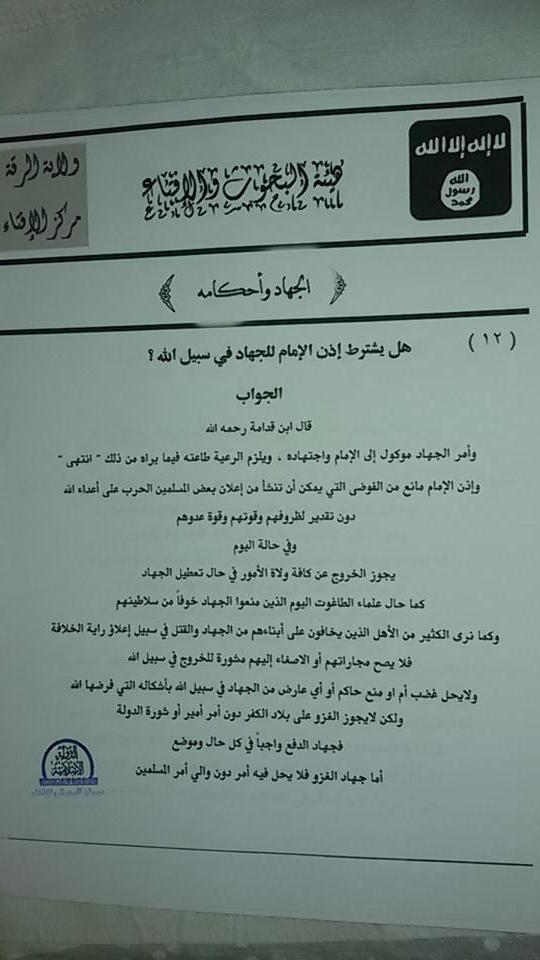

Specimen B: Imam’s Permission to Wage Jihad

al-Buhuth and al-Eftaa’ Committee

Wilayat al-Raqqa

al-Eftaa’ Centre

Jihad and its rulings

No. 12

Q: Is the Imam’s permission required for jihad in the path of God?

A: Ibn Qudama, may God have mercy on him, said: “And the order for jihad is entrusted to the Imam and his reasoning, so one must be sure to obey him

The Archivist: Critical Analysis of the Islamic State’s Health Department

NOTE: For prior parts in The Archivist series you can view an archive of it all here. And for his older series see: Musings of an Iraqi Brasenostril on Jihad.

—

Critical Analysis of the Islamic State’s Health Department

By Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi

The Islamic State’s [IS] health department (Diwan al-Siha) is probably most familiar to UK readers, who will recognize the ‘ISHS’ (Islamic State Health Service) branding as a spin-off of the ‘NHS’ (National Health Service). The ISHS was promoted in an official Raqqa province video featuring two muhajireen medical personnel, the first of whom (originally from Australia) urges Muslim medical personnel from around the world to join IS, saying: “Muslims here are really suffering from not necessarily a lack of equipment or medicine but mainly a lack of qualified medical care.” Though the video acknowledges lack of personnel, documents not officially released by IS also show that shortages of medical supplies are a significant problem. Of all departments, the IS Diwan al-Siha is arguably the least impressive, afflicted as it is by brain drain, deficiencies in supplies and lack of innovation despite the influx of muhajireen.

Lack of innovation is a matter I have touched upon before, illustrating as a case-in-point that vaccination schedules in Syria are no different from the prior status quo. In Mosul, one will find that the department of forensic medicine, which issued death certificates in the days of government control, still exists, only now it seems to be issuing death certificates under IS rule, most likely in particular in the name of its judiciary department known as the Diwan al-Qada (wa al-Mazalim). Salaries of health workers in Ninawa also continue to be paid by the Iraqi central government. This above all represents parasitic co-optation.

On the subject of manpower, numerous documents point to brain drain as the main cause of lack of qualified medical staff. For instance, in May 2015, the Diwan al-Siha, General Supervisory Committee (which can issue general directives to IS provinces and bureaucratic departments) and the Diwan al-Qada in Wilayat Ninawa issued a joint statement giving an ultimatum for doctors, pharmacists, medical and nursing professors and other health staff who had fled to return within 30 days or face confiscation of their homes as real estate under the Diwan al-Qada. The statement justifies this ultimatum on the grounds that many means of persuasion had been tried but to no avail.

It should be noted that this was not the first ultimatum issued in response to the medical brain drain problem. A similar threat of confiscation of property was issued in October 2014 by the Diwan al-Qada targeting Mosul University medical staff, board administrators and students who had left for Baghdad and Kurdistan to complete their studies, unless they returned within 10 days.

Despite these ultimatums, the dearth of medical personnel continues. On 19 August 2015, the pro-IS Facebook page “News Agency from Mosul” posted an obituary for the prominent dentist Dr. Samir Abdullah (photo above), who was reportedly killed in “international coalition bombing” on Mosul. The page added: “This man was one of the noble ones of Mosul who refused to leave Mosul, unlike others who abandoned their people in their time of need, fearing death, hunger or anything else…God willing on the Day of Judgment we will dispute with every doctor, engineer or even student who left Mosul in the time when solidarity and standing together in the path of turning the wheel of life were needed, but praise and thanks be to God we do not need those who abandoned us as they need us.”

On a more general level, some IS fatwas issued by the Diwan al-Eftaa’ wa al-Buhuth but not released in IS media outlets point to a shortage of female doctors. For example, fatwa no. 43 posits the following question: “What is the ruling on the presence of male doctors for women’s illnesses given that there are female doctors specialising in women’s illnesses but are few in number?” The response stipulates that the “principle is that the women should go to a female doctor to treat her and she should make an effort to look for that,” only resorting to a male doctor by necessity. In this case, part of the problem here is IS’ dogmatic insistence on preventing what it sees as sinful gender mixing in public.

Fatwa no. 37 appears to acknowledge that the quality of medical service inside IS territory may not quite match that of territories outside its rule, as travel to ‘Dar al-Kufr’ (the abode of disbelief) is permitted if a medical condition cannot be treated inside ‘Dar al-Islam’ (the abode of Islam: i.e. the Caliphate), responding to a particular question about whether one could travel to “areas of the [Assad] regime out of need.” Similarly in Mosul, a condition under which travel to non-IS areas is allowed is a certified document from the Diwan al-Siha that one’s illness cannot be treated inside Wilayat Ninawa (which, of all IS-held areas, will have the most developed health infrastructure).

Undoubtedly in response to the exodus of medical personnel and students and shortages, IS has been keen to encourage new cohorts of medical students, thus the opening of a medical college in Raqqa city, trying to elevate IS’ de facto Syrian capital to the same level as its de facto Iraqi capital of Mosul whose university already had a medical college. This month I have also found a statement from the Diwan al-Siha’s “Medical Sciences University” (this appears to be a new name for the medical college of Mosul University) encouraging applications from graduated high school students. Statement and full translation below.

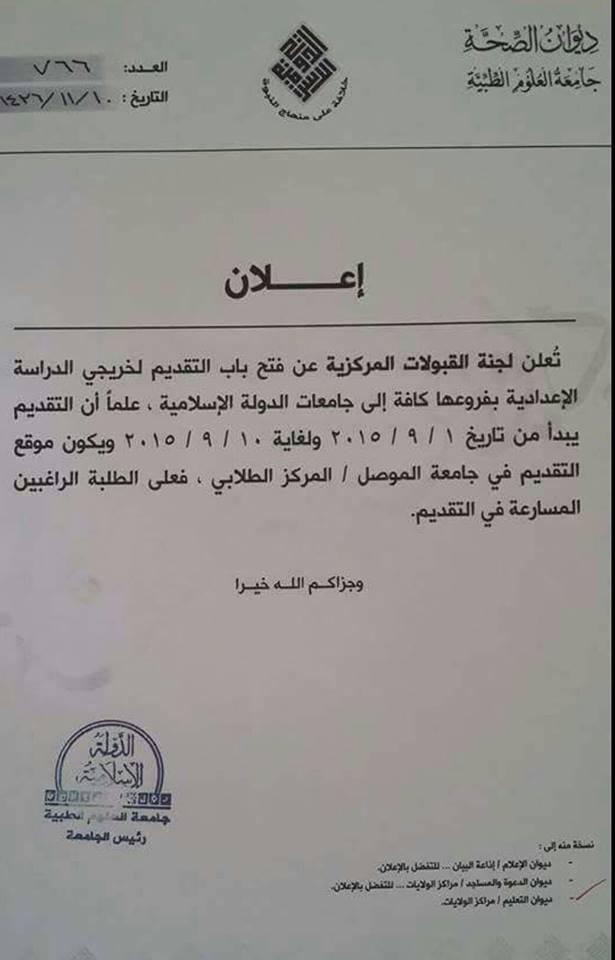

Specimen A

“Diwan al-Siha

Medical Sciences University

Caliphate on the Prophetic Methodology

No. 766

Date: 1 Dhu al-Q’ida 1436 AH [16 August 2015]

Announcement

The Central Acceptances Committee announces the opening of the door if application for preparatory study graduates in all its divisions to the universities of the Islamic State. Let it be known that application begins on 1 September 2015 until 10 September 2015, and the place of application will be in Mosul University/Students Centre. So students wishing to apply should hurry to do so.

And may God reward you best.

Islamic State

Medical Sciences University

Head of the University

Copy to:

– Diwan al-‘Ilam [Media Department]: Idha’at al-Bayan [the radio station]- to go ahead to broadcast

– Diwan al-Da’wa wa al-Masajid: Wilayat Centres- to go ahead to broadcast

– Diwan al-Ta’aleem: Wilayat Centres”

Problems in equipment and medical provisions foremost come to light in documents showing the Diwan al-Siha’s attempts to introduce price controls on pharmaceutical goods and operations. For instance, in October 2014, price limits were introduced for childbirth operations in Deir az-Zor province, fixed at 15,000 Syrian pounds for Caesarean operations and 10,500 Syrian pounds for normal operations, with the child to be kept in hospital for 12 hours after birth. These regulations were introduced, according to the statement, on account of exploitation and to assist the poor.

In the same month, the Diwan al-Siha in the Mosul area instated regulations on profits pharmacies could make in selling goods, in light of increases in prices for drugs to treat chronic illnesses. The following month, controls on profits of pharmacies in Deir az-Zor province were imposed so as not to exceed 20%. Quality and central control also seems to be an issue as IS has sought to require pharmacies to obtain licenses to operate, stipulating further that medicines must not be exposed to sunlight and the requirement of a fridge to store certain medicines.

As with the issue of medical personnel, part of the problem here appears to be IS’ own making. In May 2015, a

The Archivist: 26 Unseen Islamic State Administrative Documents: Overview, Translation & Analysis

NOTE: For prior parts in The Archivist series you can view an archive of it all here. And for his older series see: Musings of an Iraqi Brasenostril on Jihad.

—

26 Unseen Islamic State Administrative Documents: Overview, Translation & Analysis

By Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi

Introduction

Of all jihadist groups, the Islamic State [IS] by far has presented the most comprehensive, ostensible bureaucratic structure as part of its claimed state project, embodied foremost in a system of diwans (government departments) since the declaration of the Caliphate in June 2014. The best means to analyse the nuances of this set-up is through looking at documents issued by these departments that have not been officially released in IS’ media outlets.

Here, numerous shades emerge that go beyond simple statements such as ‘IS provides services.’ For example, one pattern in the documents from the IS takeover of parts of Iraq is that the Diwan al-Khidamat (services department) in a given city is normally composed of the same staff, workers and offices of already existing government service offices in that city. It is simply that the personnel have been compelled to return to work under threat of confiscation of their homes. For a more in-depth survey, see my recent paper in the academic journal Perspectives on Terrorism primarily based on my current archive of IS documents and other collections of mine currently totalling over 200 specimens.

This post presents 26 further documents not previously in the public domain, obtained from a businessman from a town in northeast Aleppo province that is currently a stronghold of IS. For reasons that are self-evident, this person’s exact location and identity cannot be revealed, but it may be added that this person does business across IS territory, including regular trips to Mosul and Anbar. Though not necessarily a hardline, ideological supporter of IS, he nonetheless finds the security environment amenable to doing business: a common advantage perceived by Syrians who make investments and conduct transactions in IS territory.

Islamic State vs. Jabhat al-Nusra Administration

Before proceeding to the selection of documents, one question worth pondering- first suggested to me by Aaron Zelin- is comparing the IS administration with that of Jabhat al-Nusra, Syria’s al-Qa’ida affiliate. To put it briefly, Jabhat al-Nusra’s administrative structures lack the same sense of comprehensiveness and consistency. Jabhat al-Nusra does not have the same level of contiguous territory and urban strongholds, and the extent of its presence varies considerably from one place to another. Further, Jabhat al-Nusra is not claiming yet to be a state.

The main Jabhat al-Nusra administrative bodies that can be identified are the Dar al-Qada (Judicial Body), the Maktab al-Da’wa wa al-Irshad (Da’wa and Guidance Office) and al-Idarat al-Aama lil-Khidamat (Public Administration for Services). Broadly speaking, the Dar al-Qada corresponds to IS’ Diwan al-Qada wa al-Mazalim and Diwan al-Hisba, dealing with legal matters such as real estate and enforcement of Shari’a justice (including harsher hudud punishments like stoning fornicators to death), while the Maktab al-Da’wa wa al-Irshad corresponds to IS’ Diwan al-Da’wa wa al-Masajid (Da’wa and Mosques department), and al-Idarat al-Aama lil-Khidamat to the Diwan al-Khidamat.

However, these bodies do not exist in every place where Jabhat al-Nusra has a presence, and sometimes functions are blurred. The Dar al-Qada can be clearly identified in Idlib towns controlled by Jabhat al-Nusra, such as Sarmada, Salqin and Darkush, but in at least one instance the Dar al-Qada seems to have assumed entered into the realm of provision of public services, with the undertaking of a project to reform the main road in Sarmada. Even so, evidence suggests that Jabhat al-Nusra continues to allow civilian local and service councils in Sarmada to operate and provide services such as fixing water pumping lines, contrasting with IS co-optation of such bodies in cities like Raqqa whereby they only have the Diwan al-Khidamat label now. More recently, as part of the Jaysh al-Fatah coalition that has driven the regime out of all major towns in Idlib province since the spring, Jabhat al-Nusra has agreed with the other factions in Jaysh al-Fatah on the formation of a judicial council that is supposed to be “independent in its decisions and rulings, with no right for any faction to intervene in it.” The council is also supposed to unify judiciary authority in all areas liberated at the hands of Jaysh al-Fatah. This development comes amid complaints from the Islamic Commission for the Administration of Liberated Areas (mainly linked to Ahrar al-Sham) that some members of Jabhat al-Nusra have attacked its branches in places like Kafr Nabl.

Moving toAleppo province, one will note the Dar al-Qada branch in Hureitan, which claims authority also over Kafr Hamra and Anadan. Here the Dar al-Qada is undoubtedly supported by the jihadi coalition Jabhat Ansar al-Din that has a presence in these towns (most notably the coalition’s main component Jaysh al-Muhajireen wa al-Ansar). Further up north in Azaz, the Jabhat al-Nusra presence has been limited to bases with control of one of the mosques in the town (the Mus’ab ibn Umair mosque), railing against the public school system in Azaz and offering alternative education for children.

Nevertheless, with talk of the establishment of a U.S.-Turkish safe zone stretching from Azaz to Jarabulus in the north Aleppo countryside, Jabhat al-Nusra has evacuated most of its bases in the Azaz area and is primarily operating as a small military force to provide limited reinforcements for the rebels fighting IS to the east of Azaz (these rebels being primarily the Levant Front and Ahrar al-Sham, with smaller contributions from mainly Levant Front break-offs like Thuwar al-Sham and Jaysh al-Mujahideen elements). These Jabhat al-Nusra members on the frontlines are mostly locals, while the remainder have already gone to Idlib province.

Thus it can be seen how much more complex the picture is with Jabhat al-Nusra administration. The bodies do not have a uniform presence and the group’s approach seems split between a more hardline approach embodied in the rise of the Dar al-Qada and the more traditional picture of Jabhat al-Nusra as a faction willing to work with others in administration. In 2013 what was then the Islamic State in Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) indulged in the latter to a degree in the occasional issuing of joint statements for defensive projects and the like.

The Documents

Below, each document is translated and notes provided where applicable.

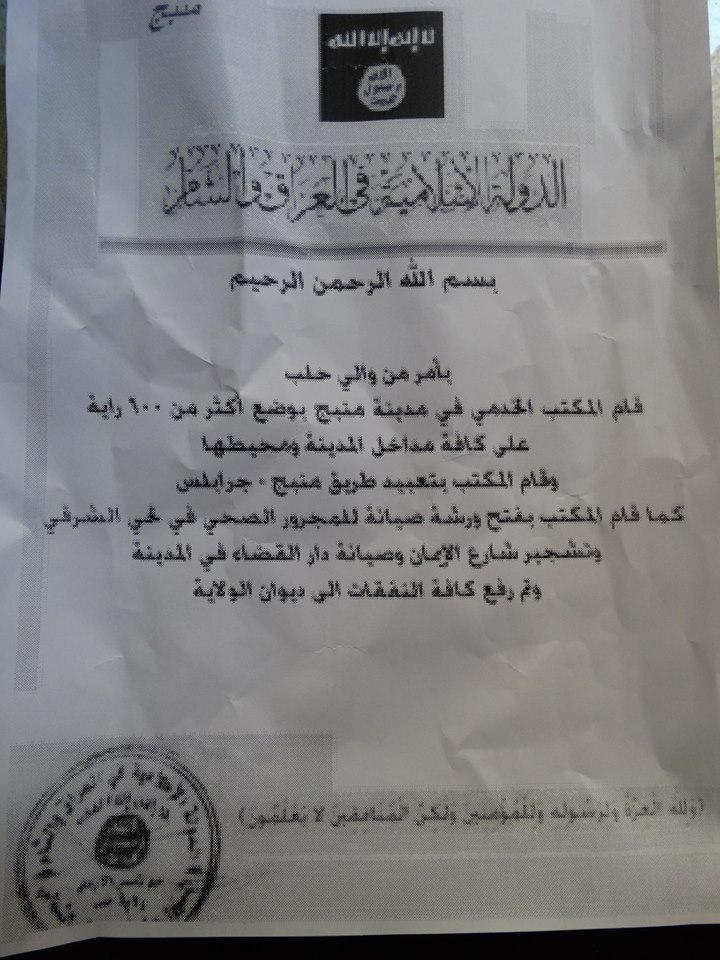

Specimen A: Activities of the services office, Manbij, Aleppo

Manbij

Islamic State in Iraq and al-Sham

In the name of God, the Compassionate, the Merciful

By order of the wali [provincial governor] of Aleppo, the services office in the town of Manbij has placed more than 600 flags on all the entrances to the town and its surrounding. The office has also made the Manbij-Jarabulus road passable for traffic, and has opened a maintenance workshop for the sewage system in the eastern quarter, has planted trees on al-Imaan street, and has done maintenance work on the Dar al-Qada in the town. And all the expenses have been referred to the Diwan al-Wilaya.

And glory belongs to God, His Messenger and the believers but the hypocrites don’t know it.

Islamic State in Iraq and al-Sham

Abu [?] Al-Azadi

Wilayat Halab

Notes: Dating uncertain. The ‘Diwan al-Wilaya’ (Province Department) appears to be the same as the “General Administration” (al-Idarat al-Aama) for a given Islamic State province. A similar interchange of names can be observed in some documents regarding healthcare labelled ‘Diwan al-Siha’ (Health Department) and others labelled ‘al-Idarat al-Tibbiya’ (Medical Administration).

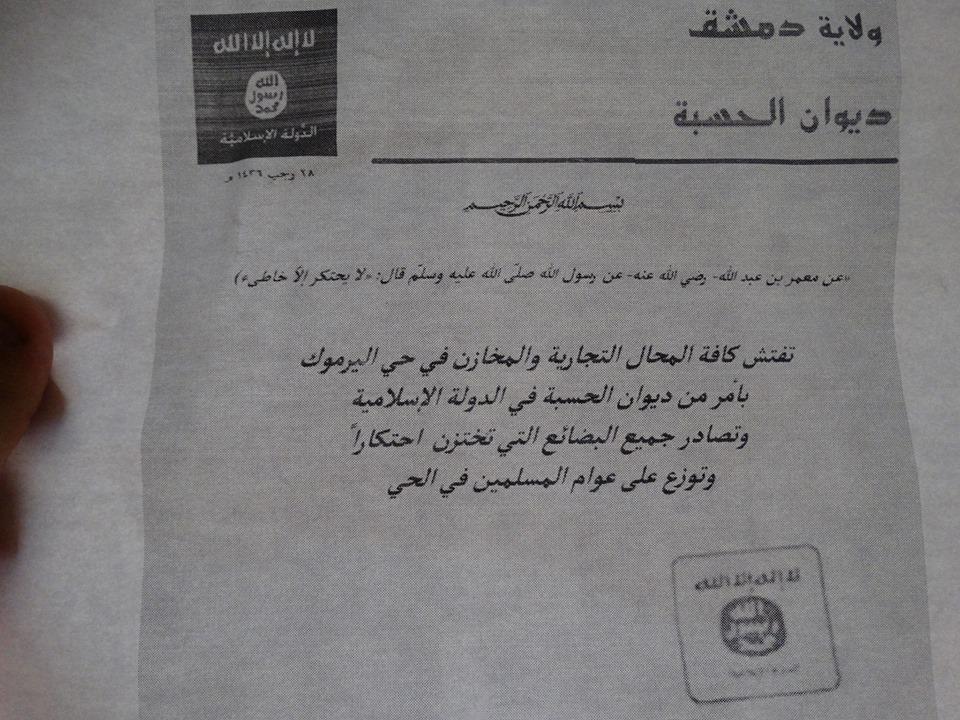

Specimen B: Prohibition on hoarding of goods, Yarmouk, Damascus

Islamic State

Wilayat Dimashq

Diwan al-Hisba

28 Rajab 1436 AH [17 May 2015]

In the name of God, the Compassionate, the Merciful

On