Click here for the first part in this video series.

—

________________

To inquire about a translation for this video message for a fee email: [email protected]

Category: Ḥarakat Aḥrār al-Shām al-Islāmīyyah

Jihadology Podcast: Syria Status Update with Charles Lister

Charles Lister comes on the show to discuss a wide range of topics related to the current situation in Syria:

- The background and evolution of Jaysh al-Fatah

- What Jaysh al-Fatah has meant to rebel and Jabhat al-Nusra victories in Syria

- The recent formation of a Jaysh al-Fatah branch in the south and what the southern front in the war currently looks like

- How the regime, Iran, and Hizballah have reacted to the changing military dynamics on the ground

- The recent fighting between the Kurds and the Islamic State in northern al-Raqqah governorate

Links:

- Charles Lister (@Charles_Lister) on Twitter

- Aaron Y. Zelin (@azelin) on Twitter

- Charles’ forthcoming book “The Syrian Jihad: Al-Qaeda, the Islamic State and the Evolution of an Insurgency,” which comes out on September 24

The show is produced by Karl Morand. If you have any feedback you can email [email protected] or find us on Twitter: @JihadPod

You can subscribe to the show in iTunes or with the show’s RSS feed.

Download this Episode (46.5 mb mp3)

Ramāḥ Media Foundation presents a new video message from Ḥarakat Aḥrār al-Shām al-Islāmīyyah: “Vanguards of Victory #2”

Click here for the first part in this video series.

—

_______________

To inquire about a translation for this video message for a fee email: [email protected]

GUEST POST: Ahrar al-Sham Spiritual Leader: The Idol of Democracy Has Shattered

NOTE: As with all guest posts, the opinions expressed below are those of the guest author and they do not necessarily represent the views of this blogs administrator and does not at all represent his employer at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy.

Jihadology.net aims to not only provide primary sources for researchers and occasional analysis of them, but also to allow other young and upcoming students as well as established academics or policy wonks to contribute original analysis on issues related to jihadism. If you would like to contribute a piece, please email your idea/post to azelin [at] jihadology [dot] net.

Click here to see an archive of all guest posts.

—

Ahrar al-Sham Spiritual Leader: The Idol of Democracy Has Shattered

By Sam Heller

On 26 May, Ahrar al-Sham’s chief shari’ah officer “Abu Muhammad al-Sadeq” issued a treatise on Twitter titled “And the Idol Has Shattered” – the “idol,” in this case, being democracy. Drawing on Algeria and Egypt’s aborted democratic experiments, Abu Muhammad argued that democracy is, in real practice, a trap for would-be Islamist participants.

Abu Muhammad was, on one level, stepping into the middle of an intra-Islamist and -jihadist controversy that has been roiling over the past several weeks. In that sense, his tweets (translated below) are another example of Ahrar threading the needle, reconciling the forces of the Syrian revolution with global jihadism in the interest of rebel unity and victory. And on another level, Abu Muhammad’s argument provides further insight into what might be an acceptable post-Assad Syrian political order for Ahrar al-Sham – which by now is arguably the strongest, most relevant fighting force within the Syrian rebellion.

The intramural Islamist/jihadist blowup into which Abu Muhammad inserted himself dates back to McClatchy’s 20 May interview with Jeish al-Islam commander Zahran Alloush. Alloush – one of Syria’s most powerful Islamist rebel chieftains – seemed to moderate his earlier rejection of democracy, saying, “After the fall of the regime, we’ll leave the Syrian people to choose the sort of state it wants.” (To their credit, McClatchy’s Roy Gutman and Mousab Alhamadee challenged Alloush on his reversal.)

Salafi-jihadist ideologue “Abu Muhammad al-Maqdisi” then weighed in on Alloush’s comments, seemingly implying that Alloush was guilty of apostasy (translation). Al-Maqdisi employed a Quranic verse (12:103) originally intended for non-Muslims and, more bluntly, said that “surrendering the fruits of jihad on the path of God to the whim of the people” amounted to “a betrayal of God, His Prophet, and the martyrs’ sacrifices.”

This sort of back-and-forth is not purely abstract. Insofar as Alloush is among Syria’s top rebels and al-Maqdisi is the prime ideological reference for Jabhat al-Nusrah, this is the sort of argument that gets people shot. (Alloush is himself a Salafist, but he reportedly hews more to the less radical ‘Ilmiyyah school of Salafism and is seen with distrust by many Salafi-jihadists.)

Abu Muhammad al-Sadeq seems to have consciously staked out a middle ground in this debate. He devotes much of his treatise to mini-histories of the Algerian and Egyptian coups, which he uses to argue that democracy, merits aside, is basically a trick. If Islamists win democratically, in his telling, the West will simply conspire with the “Deep State” to subvert those elections and crush the Islamists. He is sympathetic to the Brotherhood, who “bear an Islamic project,” but he makes it clear that the path forward is armed revolution and jihad. Currying favor with the West, as the Brotherhood did, is a waste of time. Abu Muhammad’s closing line seems like a reminder to Alloush that it’s pointless to pose as a “good Islamist” to the West. The West ultimately won’t make those intra-Islamist distinctions – Islamists, he says, will rise or fall together.

Abu Muhammad seems to reserve stronger language for his critique of al-Maqdisi’s position. Those who target Muslims who participate in the democratic process are, flatly, “wrong.” Waging war on democracy is “foolish,” “reckless” and likely to “shed sacrosanct (Muslim) blood” – a grave offense. When Abu Muhammad says that an appropriately Islamic electoral process “is not a squandering of the fruits of the jihad,” he seems to be clapping back directly at al-Maqdisi. Abu Muhammad warns that rebels must unite around their own Islamic project “before any claim can be imposed on them from without,” maybe a reference to regional or Western meddling, or maybe another allusion to al-Maqdisi – who, after all, is not Syrian and has not himself come to Syria to join the fight.

It doesn’t seem like a throwaway point when Abu Muhammad emphasizes the need for the warrior’s jihad to be coupled with “wise, just policy,” siyassah shar’iyyah hakimah. “Siyassah shar’iyyah” is frequently invoked by Ahrar, and it seems to translate roughly to being realistic and savvy, or to setting priorities. “Siyassah shar’iyyah” means you adhere to your ideological precepts but, within those lines, you also don’t do something ignorant – like announcing a war on the whole world, all at once.

In terms of what Abu Muhammad’s treatise reveals about Ahrar’s preferred political end state, his argument is long on the need for Syria’s Islamic factions to unify around an Islamic project and short on the details of what that project should look like – and deliberately so, by all appearances. When Abu Muhammad references the Quran’s Surat Ali ‘Imran (3:7), he seems to be telling his audience of fellow rebels to focus on the points that clearly unite them and leave the ambiguous details for later.

What can be taken from Abu Muhammad’s points are that Ahrar doesn’t necessarily object to something democracy-like, or to a representative electoral process with a clearly Islamic reference. If Syrians want to elect representatives who will deliberate on how best to implement the rule of God as expressed in an Islamic constitution, fine.

This, of course, is not a new position for Ahrar. One of the threads that has run through the Syrian revolution is that Ahrar al-Sham – which went from some motivated Salafists in Lattakia and Hama to the premiere rebel fighting force – has basically remained a political and religious constant. The revolution around Ahrar al-Sham has changed with time; Ahrar has not. What Ahrar’s Abu Muhammad al-Sadeq is saying in May 2015, then, is basically what Ahrar (or the Ahrar-dominated Syrian Islamic Front) was saying in January 2013 (see page 19 of Aron Lund’s report on the SIF). Ahrar refuses to put the sovereignty of God up for a vote, but electoral structures are acceptable as part of the implementation of Islamic rule. In a later piece, Lund aptly compared this political arrangement to “a Sunni version of Iran,” a “republican theocracy.”

Given Abu Muhammad and Ahrar’s emphasis on rebel unity, it seems possible that Ahrar would sign onto a maximally inclusive political order within its religious conditions. And there is more than one way to have an Islamic state, ranging from the ultra-literal application of non-codified Islamic law to something as comparatively modern as a civil-looking body of law with the teachings of Islam enshrined as the supreme constitutional reference.

The fundamentally Islamic character of a post-Assad Syria, however, does not seem to be up for debate. Ahrar has seen the Algerian and Egyptian experiences and – as Abu Muhammad drives home with a recurring Quranic reference (Quran 59:2) – taken warning of democracy. Ahrar may be politically flexible, but any settlement in Syria that doesn’t satisfy Ahrar’s religious terms is apparently off the table.

Abu Muhammad al-Sadeq’s collected tweets, 26 May 2015:

And the Idol Has Shattered

Musings on Events in Egypt

Sayeth God Most High: “So take warning, O you with eyes to see!” [Quran 59:2] There is truth in the saying, “History repeats itself,” and yet are there those who take warning?!

The events of Egypt have recalled the events of Algeria some twenty years previous, demonstrating to all those with foresight the falseness and failure of democracy. I do not speak here about democracy in terms of the religious ruling on it. Rather, I speak about democracy’s practical utility as a means of change when those bearing the Islamic project are the leading candidates.

In Algeria in 1990, the Islamists won elections with more than 80 percent of the votes, empowering them, according to the principles of democracy, to form a government and change the constitution. The West and the East quickly took heed of that, and so they suggested to their associates that they dissolve the parliament. The Islamists started with protests and peaceful sit-ins, just as happened in Egypt

New statement from Jabhat al-Nuṣrah [, Aḥrār al-Shām and Faylaq Ḥomṣ]: "About the Recent Events in Rural Northern Ḥomṣ"

Click the following link for a safe PDF copy: Jabhat al-Nuṣrah [, Aḥrār al-Shām and Faylaq Ḥomṣ] — “About the Recent Events in Rural Northern Ḥomṣ”

______________

To inquire about a translation for this statement for a fee email: [email protected]

GUEST POST: A Strong Ahrar al-Sham Is A Strong Nusra Front

A Strong Ahrar al-Sham Is A Strong Nusra Front

By Maxwell Martin

Members of Ahrar al-Sham and the Nusra Front at a public reconciliation meeting affirming their allegiance

Following the merger of two of Syria’s most prominent Islamist insurgent groups (Suqur al-Sham into Ahrar al-Sham), some commentators concluded that they were moving to counterbalance the Nusra Front, al-Qaeda’s official Syrian affiliate. But are Syrian Islamists interested in countering the al-Qaeda affiliate or will they enable it by bringing its behavior more in line with Syrian revolutionary values?

Ahrar al-Sham and the Nusra Front on a collision course?

After Ahrar al-Sham, a highly influential salafi armed group in Syria, absorbed allied Islamist faction Suqur al-Sham last month, a number of observers noted that the move appeared designed to “counter” the growing power of the Nusra Front, al-Qaeda’s official Syrian affiliate. “Are Syrian Islamists moving to counterbalance al-Qaeda?” asked Charles Lister in a recent column for the Brookings Institution. Answering this question in the affirmative, Lister added that Islamist groups actually share some fundamental objectives with the United States and its allies, among them, “to combat extremism and re-assert Syrian values of equality across ethnicity and sect.” Suleiman al-Khalidi, writing for Reuters, noted that the merger between Ahrar al-Sham and Suqur al-Sham “counters al-Qaeda’s clout,” later describing Ahrar al-Sham as a “rival” to Nusra.

Why would Ahrar al-Sham be moving now to counter Nusra, one of its closest allies in the fight against the Assad regime in Syria? Ahrar al-Sham, the argument goes, has grown uncomfortable with Nusra’s increasingly assertive behavior, particularly in the north where the group has, since July 2014, attacked and destroyed several more moderate Western-backed groups, withdrawn from joint governance schemes with other rebels, and established an exclusivist jihadi-only court system that rules according to a constrictive interpretation of Islamic law that is out of sync with local sensibilities. Ahrar al-Sham and its Islamist allies, being both more representative of the local population and more moderate, therefore have an interest in checking Nusra and preventing it from turning into a copy of the Islamic State.

Battlefield symbiosis

Some readers of those arguments may have found it curious, then, that only two days after the Ahrar al-Sham merger purportedly aimed at countering Nusra, both groups teamed up to achieve the most important rebel victory in more than two years: the takeover of Idlib city from the regime, only the second provincial capital to fall completely into rebel hands. The victory was a boon to both groups, extending their influence and territorial control while boosting rebel morale after a series of setbacks. For Nusra, the victory was especially important: it had gained an important foothold in the largest rebel-held city in Syria not controlled by the Islamic State and in so doing had demonstrated its anti-regime credentials in spectacular fashion. The victory brought it and al-Qaeda one step closer to reclaiming the mantle of global salafi-jihadism after having lost much ground to the Islamic State between summer 2013 and fall 2014. And it would have not been possible without Ahrar al-Sham.

What are we to make of this? Can we reasonably describe Ahrar al-Sham as “countering” the Nusra Front when both groups have and continue to feed off each other’s successes?

A different kind of countering

The answer to this question requires us to more carefully specify what we mean when we say that Ahrar al-Sham is moving to “counter” Nusra or that it will act as a “counterweight” or “counterbalance.” Specifically, we can think about two important ways in which Ahrar could counter Nusra. First, Ahrar could act as a strategic counterweight by working to alienate the latter from the broader insurgency. We can call this “strategic balancing.” This type of countering would entail, at a minimum, cutting ties with the Nusra Front and abstaining from any action that helps it expand its territorial reach and garner popular support. At a maximum, it would include actively degrading the Nusra Front militarily. This is what would be required of a group committed “to combat extremism and re-assert Syrian values of equality across ethnicity and sect.”

However, Ahrar al-Sham could also act in a much more limited capacity and provide a check on certain Nusra behaviors, particularly on the local level and in terms of the group’s treatment of civilians. We can call this “local balancing.” In local balancing, Ahrar al-Sham would seek to bring Nusra’s behavior back in line with Syrian sensibilities and within the bounds of revolutionary acceptability. In this case, Ahrar al-Sham could counter Nusra’s increasingly assertive, extremist and unilateral approach to ruling rebel-held territories. But Ahrar al-Sham in this case would not be preventing the Nusra Front from extending its presence and influence into new territories, participating cooperatively in governance, maintaining bases and training camps, and carrying out da’wa—religious outreach and indoctrination—activities with local populations. In other words, Ahrar could counter some Nusra behaviors with which it does not agree, particularly in governance, but not the group itself.

More convergence than divergence

So what is the state of the Ahrar al-Sham-Nusra Front relationship—strategic balancing or local balancing? The evidence indicates that it is the latter, not the former, meaning Ahrar al-Sham’s behaviors are not likely to help root out al-Qaeda in any meaningful sense from the insurgency or to prevent Nusra from continuing to expand its influence in Syria. What it is likely to do is to keep Nusra’s most regressive tendencies in check (possibly helping it generate more popular support and legitimacy than it has already garnered).

The main source of friction of late between the two groups indicates Ahrar al-Sham will tend toward local balancing. Much of Ahrar al-Sham’s apprehensions are a result of Nusra’s behavior in the north and its approach to governance, represented in Dar al-Qada, its jihadi-only court network that is strong in much of Idlib and parts of Latakia and Aleppo provinces. Since it was established in July 2014, Dar al-Qada—which is in most cases directly subordinate to the Nusra Front with allied (and even more extreme) jihadi factions such as Jund al-Aqsa participating—has aggressively instituted a range of extreme legal and social codes that other groups, including Ahrar al-Sham, have been loath to implement. The list of reported abuses that Dar al-Qada, Nusra, and its allies have committed is lengthy and includes whipping a man in July 2014 for cursing religion, publicly shooting two women in a single week for prostitution, stoning a man and woman for adultery, forcing Druze communities in Idlib to convert to Islam, raiding an opposition radio station and women’s center in Kafranbel, and beating several women and activists in addition to lesser forms of extremism such as forcing cafes with billiards, computer games, and foosball to close.

On the ground, Ahrar al-Sham contingents have been opposed to these practices and have worked to prevent them from spreading. The Islamic Commission, an Ahrar al-Sham-backed governance body that includes a network of courts, does not implement such regressive regulations. Its courts mostly implement the Unified Arab Code, a written interpretation of Islamic law that more extremist factions reject. Ahrar al-Sham-backed courts have ignored some of the harsher regulations such as stoning and hand

New statement from Jaysh al-Fataḥ: “Message To Our People In Idlib”

Click the following link for a safe PDF copy: Jaysh al-Fataḥ — Message To Our People In Idlib

_______________

Source: Twitter

To inquire about a translation for this statement for a fee email: [email protected]

Ramāḥ Media Foundation presents a new video message from Ḥarakat Aḥrār al-Shām al-Islāmīyyah: "You Will Not Get Through"

_______________

To inquire about a translation for this video message for a fee email: [email protected]

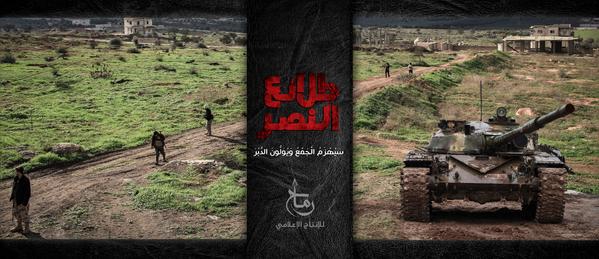

Ramāḥ Media Foundation presents a new video message from Ḥarakat Aḥrār al-Shām al-Islāmīyyah: "Vanguards of Victory"

______________

To inquire about a translation for this video message for a fee email: [email protected]

New video message from The Islamic State: "Repentance From Tens [of Members] of Jabhat al-Nuṣrah and Aḥrār al-Shām – Wilāyat Ḥalab"

______________

To inquire about a translation for this video message for a fee email: [email protected]