NOTE: As with all guest posts, the opinions expressed below are those of the guest author and they do not necessarily represent the views of this blogs administrator and does not at all represent his employer at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy.

Jihadology.net aims to not only provide primary sources for researchers and occasional analysis of them, but also to allow other young and upcoming students as well as established academics or policy wonks to contribute original analysis on issues related to jihadism. If you would like to contribute a piece, please email your idea/post to azelin [at] jihadology [dot] net.

Click here to see an archive of all guest posts.

—

Women of The Islamic State: Beyond the Rumor Mill

By Charlie Winter

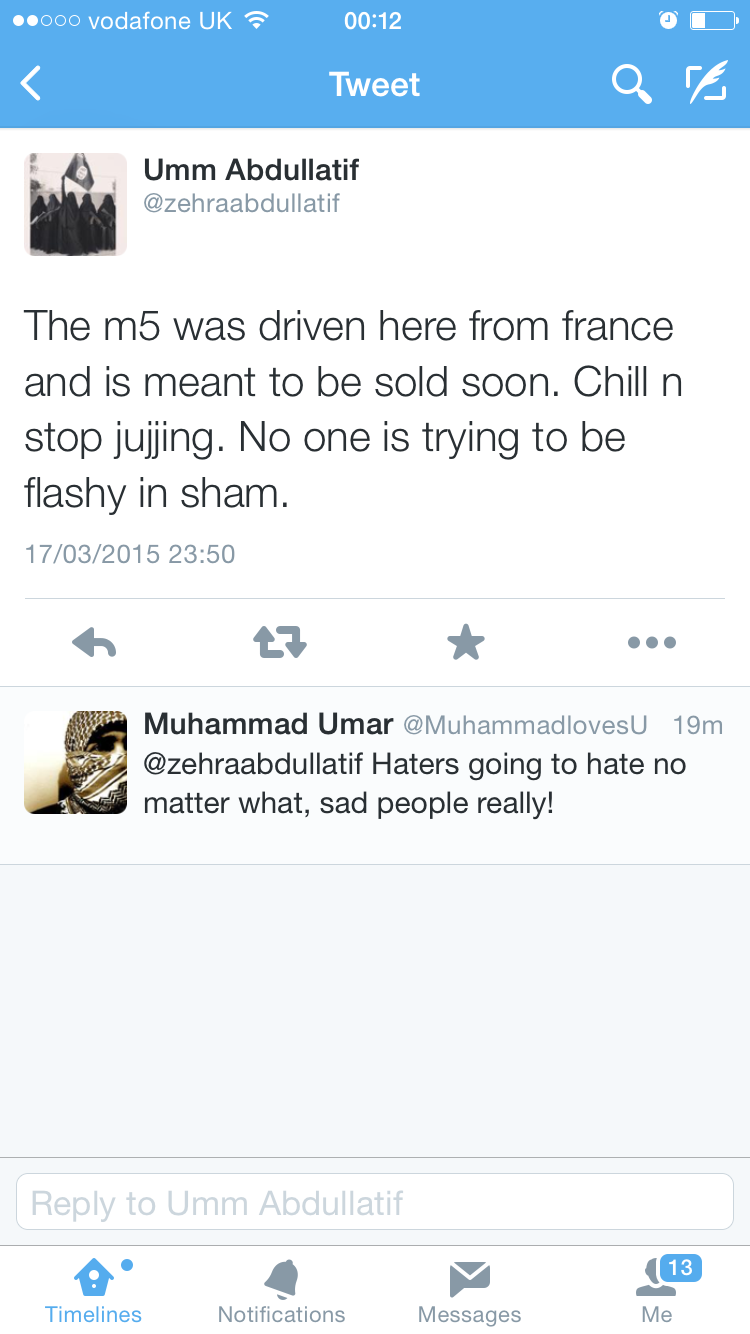

Upon hearing that a young woman had recently tweeted a series of photographs of herself and five others reclining on the bonnet of a white BMW M5 holding AK47s of various styles, one could be forgiven for thinking that it was a case of hip hop fanboyism (or, indeed, fangirlism), an assumption that would perhaps be reinforced by the words it was accompanied with – “Don’t mess with ma clique – from the US and the Oz”. However, this was nothing to do with hip hop culture, it was IS propaganda. Indeed, in her next tweet, Umm Abdullatif al-Australi, using the now-suspended handle @zehraabdullatif, spoke of that oft-peddled myth, the “five star jihad”, the idea that, if one joins in with Islamic State’s (IS) political project, then they are in for a glamourous adventure filled with shiny weapons and fast cars, one that somehow manages to be totally in line with IS’s hugely austere version of Islamism. This is a misleading conception. Akin to how gang culture has been glamorized in an attempt to make it more appealing to potential gang-members, IS supporters peddle a similar narrative in order to romanticize their “adventure” and render it more appealing to potential recruits.

Photographs like these, of girls and women engaging in weapons training and cavorting around bombed-out buildings as if they were training for urban warfare, are inaccurate. While they capture the imagination of certain less imaginative media outlets and regularly make headline news, this is not what life is like for muhājirāt (literally, migrants), the female jihadists who have joined IS. To the contrary, this narrative is a construct perpetuated by the Western girls who have joined IS as part of a propaganda strategy. It is a false image based on targeted obfuscation and exaggeration. The entire myth of the five star jihad is just an attempt to shroud IS’s extremist dystopia with excitement and romanticism, a means of drawing in the vulnerable and naive.

What, then, is life like for IS’s female recruits? There are few unofficial sources from which we can piece together a vague picture, but a fine place to start is the blog of Glasgow runaway Aqsa Mahmood, who used to tweeted from the handle @UmmLayth_. Unlike her Australian colleague, Mahmood’s version of life in the Caliphate does not appear at odds with the values of IS’s brand of salafi-jihadism. In her diary, she writes of how daily life is often “mundane”, how one’s “day will revolve around cooking, cleaning, looking after and sometimes educating the children”. There are no guns – “I will be straight up and blunt with you all, there is absolutely nothing for sisters to participate in Qital [sic]” – or cars – “these are all rumors you may have heard through some sources who themselves are not actually aware of the truth”. Mahmood even explains why there is this disparity – “the women you may have seen online participating are all part of a propaganda [sic]”. Given IS’s unprecedented ability to manipulate the internet to its messaging ends, this should not surprise.

While Mahmood’s account certainly rings more true than that of others, it is not exhaustive. In light of that, in seeking to put together a more accurate, balanced image of life for IS’s women, one must delve into the Arabic side of IS’s social media support base, its presence on forums, Twitter and blogs. While there is yet to be any wholly official messaging regarding women’s place in IS society, here, we find female supporters of IS as active as their male counterparts, just as outspoken and profligate as the men and just as quick to circulate propaganda and shout down the kuffār, nuṣayriyyīn and rāfiḍa. Long gone are the days of closed female-only jihadist forums.

Even then, though, there is a paucity of believable information about their everyday lives, apart from the odd photograph of girls gathering outside the doors of IS’s newly re-opened university in Mosul or woman sitting at a lap top typing furiously propagandizing. There is precious little to go, which is somewhat surprising, given IS’s proclivity for flooding the internet with propaganda reports about its men and children.

It is for the above reason that, when I came across a link to a document entitled “Women in the Islamic State” on Al-Platform Media, a jihadist forum popular with IS supporters until it was taken offline, I translated it. Uploaded by a user claiming to be part of the Al-Khansā’ Brigade’s media arm, the document was some 10,000 words long and dealt with a wide variety of issues, from feminism and emasculation to driving and Muhammad bin Nayef’s views on robbery.

While it is clearly stated within the manifesto that it “is not an official state policy document”, it is the closest thing we have to such a thing. The Al-Khansā’ Brigade, the all-female group that has risen to media infamy in recent months as something that has variously been reported to be IS’s women-only police force/border guarding/brothel managing/checkpoint manning organization, is not an official organ in al-Baghdadi’s political machinery. However, whatever it is, we know it exists and is sanctioned by the “state”. To refer to it as a single entity with any one responsibility is perhaps a mistaken approach – what is more likely is that the brigade serves the function of a sort of jihadist Women’s Institute, engaging in a broad range of activities, among them policing, teaching, propagandizing and guarding (not, mind you, fighting).

Hence, while it may not be an arm of the state, it is an organization that exists with IS’s blessing and, because of that, we can be confident that it will reflect the ideology of IS pretty accurately. Given that, the manifesto’s existence is significant; across its pages is written the IS ideologue’s account of what life should be like for women, how they must be treated and what responsibilities are bestowed upon them once they sign up. And, given that it is ideologues running the show, their account of life will resemble, to a high degree, the vision of IS’s most senior politicos.

The manifesto itself, written in unimaginative jihadist patois, covers a range of issues. Initially, it discusses conceptual issues, dealing with problems inherent to feminism, which is referred to scathingly as the “Western program for women”. This, its authors hold, is a phenomenon that has arisen from modernization, materialism and, worst of all, a “rise in the number of emasculated men who do not shoulder the responsibility allocated to them [by God] to the umma”. It thus follows that, by joining IS (wherever that may be), a women can “emancipate” herself from that which is forced upon her by Western cultural corruption. The implication is that the men fighting for IS are at the peak of rajūla, or masculinity, and their aura is inherently purifying and conducive to being a “good Muslim”.

The diatribe against feminism goes on: “men are serving women like they serve themselves [and, therefore] cannot distinguish themselves” from one another. This is an untenable situation for which the only remedy is for women to return to their “true role […] the harmonious way for her to live and interact amidst her sons and her people”. The authors expand upon just what this role is, without ambiguity: “the greatness of her position, the purpose of her existence is the Divine duty of motherhood”. This, coupled with being a dutiful wife, is the fundamental role bestowed upon women. It takes priority above all else. While this is not remotely surprising, it does not really chime with the rumors being peddled by the likes of Umm Abdullatif al-Australi.

Moving on from the conceptual and on to the practical, the manifesto goes on to deal with the particulars of how life in the caliphate might look. “It is considered legitimate for a girl to be married at the age of nine”, which happens to be when girls are two years into their six year-long “ideal education”, one that focuses on knitting, cooking and the religious sciences, as opposed to “strange studies […] things unrelated to religion that have no worldly use”. Once “educated” and after marrying, women’s responsibilities are stripped down to their most “pure”. “Sedentariness, stillness and stability”, her fundamental characteristics, are to be realized and reflected in daily life. As wives and mothers, IS’s female recruits are obligated to support the caliphal project from behind closed doors.

This is not to say that women are less important than men. On the contrary, they are equally important – “woman was created to populate the Earth just as man was” – the key distinction being that “she was made from Adam and for Adam”. Hence, the jihad of women, according to the idealized account of the IS worldview, revolves around a mode of existence that facilitates the violent jihad of men.

After poring over the practicalities of this “Divinely ordained” misogyny and corresponding subjugation, the author(s) turn to “real” life in the shadow of IS’s caliphate. The Al-Khansā’ media team, as it affectionately terms itself, head first to the Iraqi city of Mosul and then to Syria’s Raqqa, where they travelled to “check on the happy situation that women face and their return to what was there at the dawn of Islam”. At this stage, the manifesto becomes a little less insightful. We are left with straightforward, run-of-the-mill propaganda.

That said, it still makes an interesting read. The authors delves into what life is (or should be) like living in the shadow of the caliphate as a woman. A variety of themes are dealt with, from justice and hijab to personal security and healthcare. It goes without saying that the conditions presented are massively idealized and woefully inaccurate. It is also worth noting that a number of particularly uncomfortable truths are notable in their absence – sex slave markets and stonings to mention but two. Whatever the case, this should not be taken as a credible account of what life is like in IS-held Syria and Iraq. What it is, though, is an account of what IS want life to look like from the outside. Hence, it remains a critically important resource for understanding IS’s social and political imagining of itself.

The final portion of the manifesto, entitled “A quick comparison between the Salūli State and the Islamic State”, presents a vitriolic and unrelenting litany of offenses committed by the Saudi monarchy against Muslims in the Arabian Peninsula (“Āl Salūl” – a Quranic reference to Abdullah Ibn Ubayy Ibn Salūl, the “chief of the hypocrites” – is IS’s preferred term of reference for Āl Sa‘ūd). Regardless of the realities of life for women in the Gulf, it would be unwise to take any of what is said in this section in earnest. Arguments that we hear in the West about things such as driving are turned on their head – while the author(s) disagrees with the Saudi stance on driving, as many in the West do, they disagree with the idea of it for completely different reasons: there should be no leniency for women that take to the roads, “it does not conform with religion”, and that’s that. For the Al-Khansā’ Brigade, there should not be any discussion of it at all. As this section goes on, the plight of women – Sunni women, at least – is drawn upon as evidence that the Saudi kingdom is a pawn of kufr, a result of its istighrāb, its attempts unashamedly imitate all things Western.

When broken down section-by-section, the Al-Khansā’ manifesto is illuminating, to say the least. However, what is perhaps most important is the manner in which this document allows the analyst to insert themselves inside the mind of the female IS ideologue. From it, we can glean the specifics of the idealized vision that IS holds for women, a vision that does not sit at all well with the romanticized, action-packed imagery that the likes of Umm Abdullatif al-Australi and her cohort circulate.

Charlie Winter is a researcher on transnational jihadist movements based at Quilliam, where he focuses in particular on the Islamic State, tracking its relations with other jihadist groups. Beyond this, his research explores IS’s “state” institutions and its propaganda strategy. He has advised governments on Middle East policy and presented his findings at UK Parliament on a number of occasions.

GUEST POST: Women of The Islamic State: Beyond the Rumor Mill

Posted on

1 Reply to “GUEST POST: Women of The Islamic State: Beyond the Rumor Mill”

Comments are closed.