_______________

Source: RocketChat

To inquire about a translation for this video message for a fee email: [email protected]

_______________

Source: RocketChat

To inquire about a translation for this video message for a fee email: [email protected]

__________________

To inquire about a translation for this video message for a fee email: [email protected]

Click the following link for a safe PDF copy: al-Qā’idah in the Islamic Maghrib and Jamā’at Nuṣrat al-Islām Wa-l-Muslimīn — Congratulations To the Islamic Nation On ‘Īd al-Fiṭr 1445 AH

_________________

Source: Telegram

To inquire about a translation for this statement for a fee email: [email protected]

Click the following link for a safe PDF copy: al-Qā’idah in the Arabian Peninsula — Congratulations On the Occasion of ‘Īd al-Fiṭr 1445

________________

Source: RocketChat

To inquire about a translation for this statement for a fee email: [email protected]

—

Click the following link for a safe PDF copy: Ustād Usāmah Maḥmūd — If You Support God, He Will Support You

__________________

Source: Telegram

—

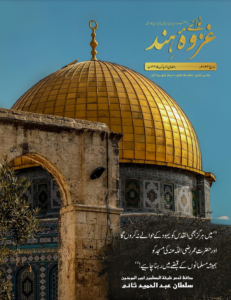

Click the following link for a safe PDF copy: al-Qā’idah in the Indian Subcontinent — Nawai Ghazwat al-Hind Magazine – March 2024

________________

Source: RocketChat

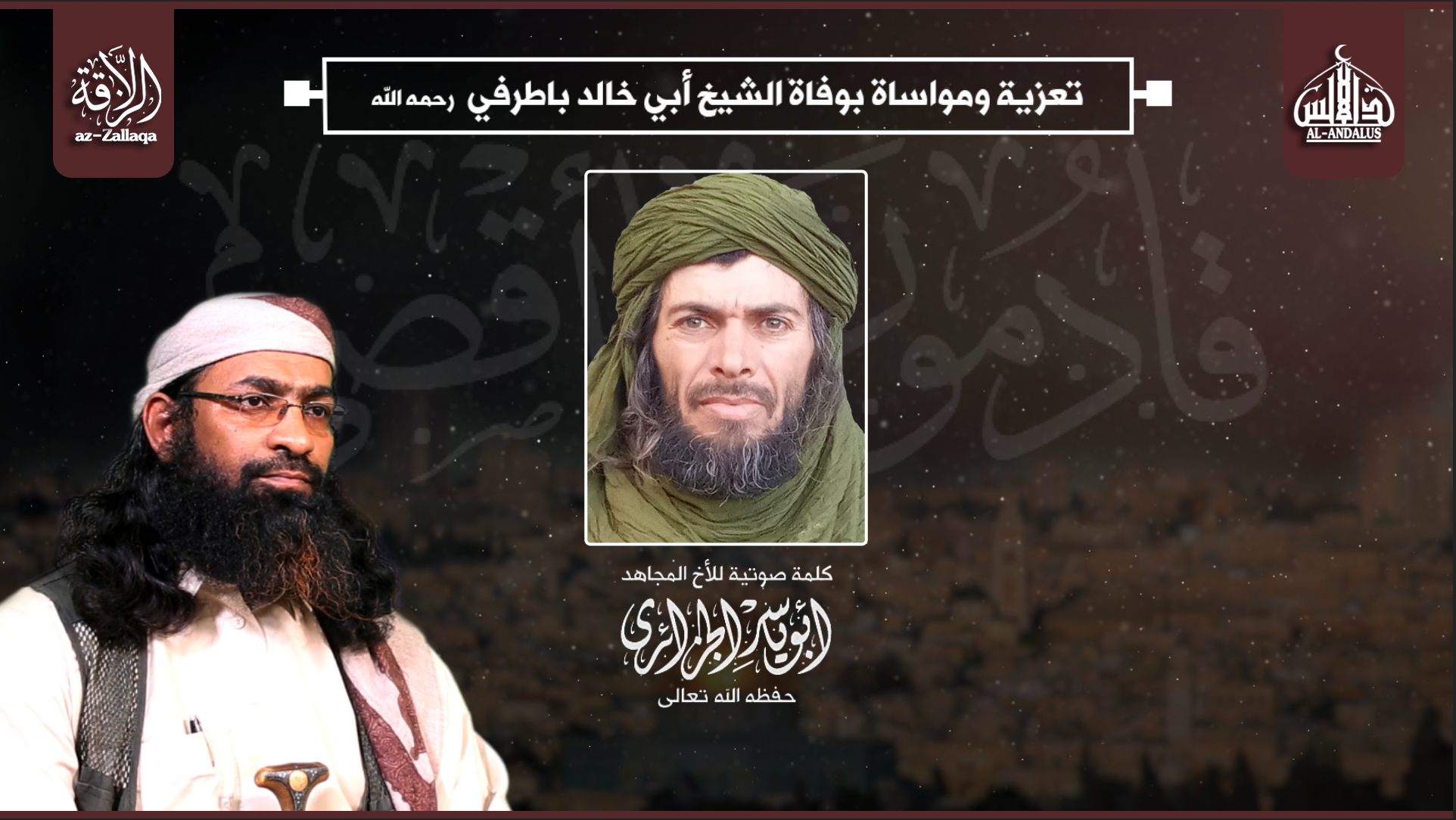

Click the following link for a safe PDF copy: al-Qā’idah’s General Command — Regarding the Death of the Leader Shaykh Khālid Bāṭarfī

_______________

Source: Telegram

To inquire about a translation for this statement for a fee email: [email protected]

Click the following link for a safe PDF copy: al-Qā’idah in the Arabian Peninsula — Regarding the Ḥūthīs’ Bombing of Muslim Homes In Radā’a – al-Bayḍā’

____________________

Source: Telegram

To inquire about a translation for this statement for a fee email: [email protected]

Click the following link for a safe PDF copy: Ḥarakat al-Shabāb al-Mujāhidīn — The Mujāhidīn Marched Through the Enemy’s Base in Baar Sanguuni

_________________

Source: Telegram