As with all guest posts, the opinions expressed below are those of the guest author and they do not necessarily represent the views of this websites administrator and does not at all represent his employer at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy.

Jihadology.net aims to not only provide primary sources for researchers and occasional analysis of them, but also to allow other young and upcoming students as well as established academics or policy researchers to contribute original analysis on issues related to jihadism. If you would like to contribute a piece, please email your idea/post to azelin [at] jihadology [dot] net.

Click here to see an archive of all guest posts.

—

Heretics, Pawns, and Traitors: Anti-Madkhali Propaganda on Libyan Salafi-Jihadi Telegram

By Nathan Vest

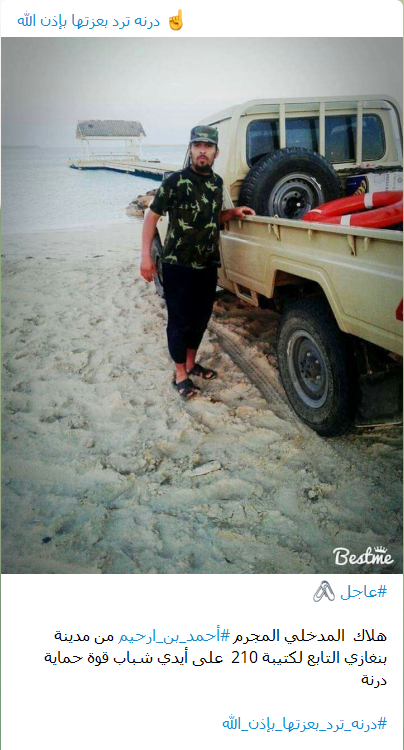

On January 23, 2019, a Libyan salafi-jihadi Telegram channel posted a photo of a Libyan National Army (LNA) fighter reportedly killed in the eastern city of Derna.i The Telegram channel claimed that the deceased fighter belonged to a movement of salafis, colloquially known as Madkhalis after their spiritual leader—Saudi cleric Rabiՙa al-Madkhali. The Madkhali fighter is just one of the many killed in a sub-conflict within Libya’s civil war, pitting salafi-jihadis against traditionalist salafis, who are sometimes described as “quietest” for their avoidance of conflict with the state.1

Since 2014, both sides have experienced waxing and waning fortunes; however, following victories in Benghazi, Sirte, and Derna, the Madkhalis are the ascendant faction. Subsequently, Libya’s salafi-jihadis are attempting to regroup and reverse Madkhali gains, and their efforts will largely depend on their ability to restore their diminished popular support. In line with these efforts, Libyan salafi-jihadis have taken to social media, particularly the messaging platform Telegram, to gain ideological and national legitimacy over the Madkhalis by portraying their traditionalist rivals as un-Islamic agents of foreign interests and traitors to Libya’s 17 February Revolution.

Salafi-jihadis and traditionalist Madkhalis may share ultra-conservative views, such as strictly applying Shariՙa law in everyday life, morally policing the public sphere, and returning Islam to its purist form, during and immediately following the life of the Muslim Prophet Muhammed. However, salafi-jihadis and traditionalists salafis diverge on the medium through which they pursue their socio-religious objectives. Whereas salafi-jihadis, as their title suggests, condone waging violent jihad against despotic regimes and their foreign backers, traditionalist salafis espouse the tenet of wali al-amr, or loyalty to the communal leader or head of state. While salafi-jihadis are quick to pronounce fellow Muslims as unbelievers and use violence to overthrow what they see as corrupt, despotic systems, traditionalist salafis abhor fitna, or intra-communal chaos and violence. Therefore, they refuse to disavow regimes and instead work through them to propagate their salafi ideologies. As such, regimes, including the Gaddafi regime and the Sisi regime in Egypt, often work by, with, and through traditionalist salafi movements. In doing so, they attempt to avert the argument that the regimes are anti-Islamic while simultaneously undermining the potential threat of salafi-jihadis to the system, via co-optation of their traditionalist rivals. Salafi-jihadis, therefore, often view traditionalist salafis as pro-regime pawns and enemies of the true salafi cause.

As other researchers have discussed, Madkhalis have evoked wali al-amr and sided with both the Government of National Accord (GNA) in the west and Khalifa Haftar’s LNA in the east to combat salafi-jihadi terrorist organizations, most notably the Islamic State (IS) and al-Qaeda-affiliated Ansar al-Shariՙa in Libya (ASL). Since 2016, salafi-jihadi groups have suffered stinging defeats in the east, and Madkhali power is growing in the west as well. These major battlefield defeats and the Madkhalis’ rising socio-political influence have greatly shaped how Libyan salafi-jihadis discuss their traditionalist adversaries, predominantly in Telegram-based propaganda.

Depicting Madkhalis as un-Islamic and enemies of proper Islamic practices is among the most prominent themes in anti-Madkhali propaganda salafi-jihadis circulate via Telegram, constituting an ad hominem attack meant to emphasize the salafi-jihadis’ religious legitimacy. For instance, on October 5, 2018, one salafi-jihadi channel accused Madkhalis of coercively working through the GNA’s President, Fayez al-Sarraj, to replace “legitimate religious education in schools which teach the al-Maliki madhhab to make room for the Madkhalis to live in mosques and schools.”ii Another channel echoed this accusation of Madkhalis undermining “legitimate” religious education, claiming that an LNA-affiliated militia in Derna was preventing studies in the city’s schools on Thursdays, replacing the classes with Madkhali lessons.iii

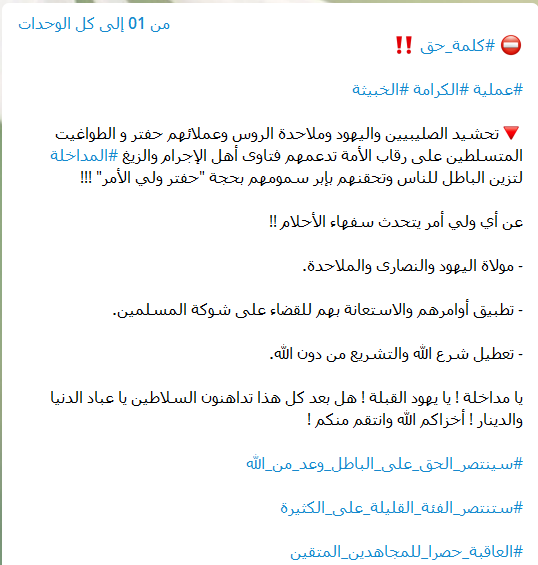

Libyan salafi-jihadis’ allegations of Madkhalis’ un-Islamic machinations also extend beyond Libya’s schools and into its mosques. For instance, they have also accused Madkhalis of closing Derna’s Al-Sahaba mosque, preventing locals from praying at one of the city’s most prominent religious centers.iv Additionally, while Madkhalis allegedly prevent “true” Muslims from worshiping, Madkhalis themselves are unable to pray correctly, “not knowing whether to pray or look at the camera,” one salafi-jihadi channel chided.v At other times, anti-Madkhali rhetoric is far less subtle, accusing Madkhalis of striving to “submit the tribe of Islam to the crusaders,” or western powers.vi Ergo, true Libyan Muslims must rally behind their religion’s legitimate champions—the salafi-jihadis—to save the Libyan religious sphere from heretical Madkhali domination.

Similarly, due to the Saudi origin of the Madkhali movement and their affiliation with the LNA and GNA—both backed by various international actors—salafi-jihadi Telegram channels regularly accuse Madkhalis of being agents of foreign interests—namely those of the UAE, Saudi Arabia, France, Russia, and Libya’s former colonizer, Italy. For example, one salafi-jihadi channel affirmed that the “scope of the conspiracy which the war criminal Haftar and the Madkhalis lead in eastern Libya” is facilitated “by Emirati and Saudi support against the people of the Qur’an.”vii

The UAE, in particular, has been among Haftar’s most ardent international backers in his fight against Islamist and salafi-jihadi actors in eastern Libya. The Emiratis have reportedly provided Haftar’s LNA with arms and training, according to the UN Panel of Experts on Libya. The UAE is also allegedly expanding the Al-Khadem air field in eastern Libya from which it could base larger fighter jets, such as the F-16 or Mirage 2000, in addition to the AT-802 Air Tractors and Wing-Loong drones already housed there. Reportedly, the UAE has deployed the Air Tractors and drones, flown by mercenary pilots, to conduct sorties in eastern Libya, and salafi-jihadi Telegram channels regularly reported drones, likely belonging to the UAE, flying missions over Derna.viii

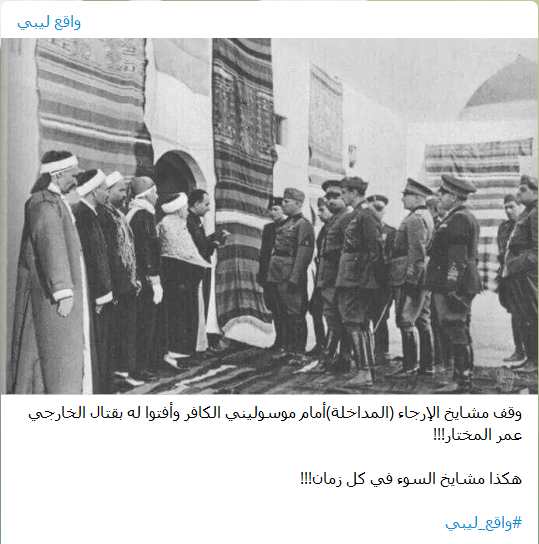

Libyan salafi-jihadi Telegram channels have also attempted to demonize their Madkhali rivals by associating them with their former Italian colonizers, who brutally ruled Libya from 1911 to 1947. In one such post, a salafi-jihadi channel posted a photo of alleged Madkhalis meeting with former Italian dictator Benito Mussolini and suggested they provided religious sanction to Mussolini’s efforts to fight Omar al-Mukhtar, a revered anti-colonial figure among Libyans.ix The implication is that just as the Madkhalis supported fascist Italy against al-Mukhtar, so too do they support Italy over patriotic Libyans today.2 Another salafi-jihadi channel was even more broad brushed in its attack, accusing “crusaders, Jews, Russian atheists, and their agents” of “mobilizing Haftar and the tyrants stepping on [Libya’s] neck, who are supported by fatwas of the people of crimes, the Madkhalis.”x

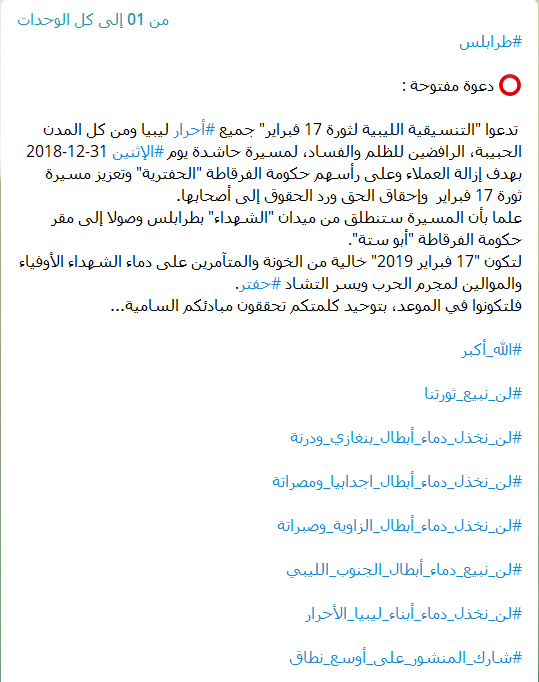

Conversely, many Libyan salafi-jihadis posit themselves as “the free sons of Libya” or the “heroes of Benghazi, Derna . . . Ajdabiyya and Misrata”, starkly contrasting their steadfast devotion to the Libyan people with the “foreign agents headed by the ‘Frigate’ Government3 and Haftar.”xi While they portray both the GNA and Haftar as subservient to foreign actors, salafi-jihadis argue that they are the sole legitimate representatives of Libyan interests, for which they have fought since the 17 February Revolution.

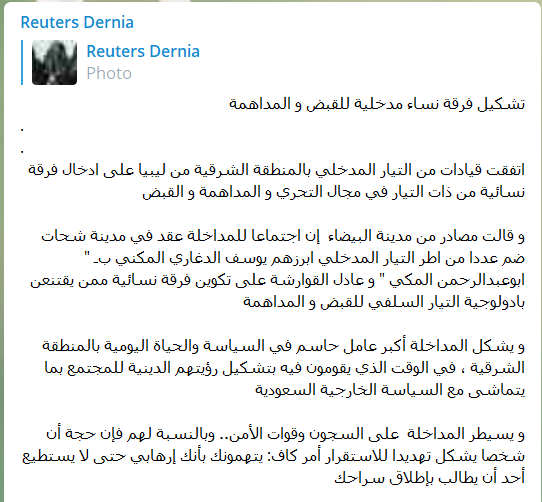

However, despite their zeal, salafi-jihadis are reeling from their losses in the east. After more than three years of fighting, Haftar finally declared victory over the Benghazi Revolutionaries’ Shura Council (BRSC), an umbrella group comprising ASL in December 2017. Haftar did the same against the Mujahideen of Derna Shura Council (MDSC) in June 2018, although fighting continued in Derna’s old city until February 2019. A post from January 14, 2019 captured the salafi-jihadi view that the Madkhalis greatly benefited from the deterioration of their position, stating that “Madkhalis form the largest, most crucial actor in politics and daily life in the east.”xii Salafi-jihadi groups such as BRSC and MDSC attempted to cultivate a society guided by the groups’ salafi ideology. However, having been defeated by the LNA and its Madkhali elements, Libyan salafi-jihadis in the east see their rivals “forming their religious vision for society in line with external Saudi politics” and see their own image of an ideal Libyan society being upended.

Having long been suppressed by the Gaddafi regime, many salafi-jihadis in Libya saw the 17 February Revolution and the post-revolutionary space as a means of constructing a puritanical Muslim society. Following their participation in the armed uprising which ended Muammar Gaddafi’s 42-year rule, salafi-jihadis set about promoting their ideology through education, proselytization, and charity services, although assassinations, kidnappings, and other campaigns of violence also accompanied the salafis’ communal works. Indeed, violent acts of salafi groups such as ASL were part and parcel to Benghazi’s security deterioration, which catalyzed the outbreak of violence in Benghazi in 2014.

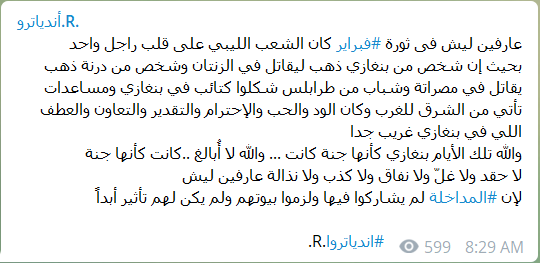

Nevertheless, having spent blood and treasure fighting against the Gaddafi regime, many Libyan salafi-jihadis view themselves as true standard bearers of the 17 February Revolution. Conversely, they view their Madkhali rivals as traitors to the revolutionary cause, as many Madkhalis either remained neutral or loyal to the Gaddafi regime until late into the revolution. As one salafi-jihadi channel rhetorically asked, “do you know why during the February Revolution the Libyan people stood with the heart of one man? Because the Madkhalis didn’t participate in the revolution. They stayed in their homes and didn’t have any influence at all.”xiii

However, to the consternation of Libya’s salafi-jihadis, Madkhalis are now deeply ingrained and influential. As mentioned above, Madkhalis are an increasingly powerful actor in eastern Libya, but they are also key players in the west as well. A Misratan Madkhali militia—the 604th Battalion—participated in some of the most intense fighting against IS in its former stronghold, Sirte. Additionally, Tripoli’s Special Deterrence Forces, or Rada, have become synonymous with the Madkhalis’ ascent in western Libya.

Since the 17 February Revolution and the dissolution of the Gaddafi regime’s security apparatus, militias such as Rada have filled the vacuum, stepping in as local security services. Rada’s leader, Abdulraouf Kara, is an adherent of the Madkhali ideology, and his militia has become Tripoli’s de facto police force, breaking up drug and kidnapping rings, securing Tripoli’s only functioning airport, and conducting counter-terrorism (CT) operations. However, in line with Madkhalis’ ultra-conservative religious and social views, Rada has also reportedly harassed and abused members of Tripoli’s LGBTQ community, as well as women walking in public without a male guardian. Additionally, Rada disrupted Tripoli’s comic book convention in November 2017 and detained its organizers for propagating un-Islamic practices and images. Rada is able to act in this manner with impunity, largely due to the militia’s role as a CT force and security guarantor in Tripoli, granting it substantial influence over the GNA. Indeed, following the September 2017 clashes between Tripolitan militias and armed groups from neighboring Misrata and Tarhouna, one Telegram channel stated that “the Madkhalis (Rada) are in one trench with the foreign agent ‘Frigate’ government.”xiv

Today, with the growing power of the Madkhalis, who support and work through two governments some Libyans perceive as illegitimate and subservient to counter-revolutionary forces in the region, salafi-jihadis consistently condemn the Madkhalis as being traitors to the 17 February Revolution. One channel bluntly claimed that “Madkhalis are enemies of the revolution and revolutionaries.”xv Another channel stated that, given their ties to the UAE and Saudi Arabia, their previous complicity with the Gaddafi regime, and their willingness to fight for Haftar, a military strongman, “Madkhalis are a refuge . . . for every tyrant of the human race.”xvi As such, Libyan salafi-jihadi channels have continued issuing a “general call to arms to young and old to wage jihad for the sake of God against injustice and tyranny”xvii and reverse the battlefield gains of Haftar, the LNA, and the Madkhalis.4 These battle calls reflect an concurrent salafi-jihadi campaign to bolster their ranks in the field, while simultaneously working to garner popular support by undermining the Madkhalis’ religious bona fides.

Nevertheless, Libya’s salafi-jihadis are currently on their back heels. They have suffered decisive blows in Benghazi, Derna, and Sirte, partially at the hands of Madkhali salafis, and as their Telegram-based propaganda reflects, salafi-jihadis largely blame turncoat Madkhalis and their foreign backers for their defeats. However, after almost five years of fighting, the Libyan conflict seems just as far away from resolution as it did in May 2014, and the country’s salafi-jihadis are down but far from out, maintaining a strong will to fight. They believe their jihad has been stolen by un-Islamic, foreign-backed traitors, and as Libya’s crisis endures, salafi-jihadis will continue to promulgate anti-Madkhali messaging in a concerted effort to cultivate religious and local legitimacy in order to undercut their Madkhali adversaries’ socio-political gains.

Nathan Vest is a research assistant and Middle East specialist at the RAND Corporation. Follow him on Twitter: @nkvest22

Author’s note: This paper is solely meant to convey and analyze what, how, and why Libyan salafi-jihadis talk about traditionalist Madkhali salafis in propaganda promulgated via salafi-jihadi Telegram channels. It is not meant to convey the author’s support for either of the two groups over the other. The author would also like to thank Jeffrey Martini and Jalel Harchaoui for their insight and guidance in support of this paper.

1 Researchers often refer to traditionalist or Madkhali salafis as “apolitical” or “quietist” salafis, in that they condemn political Islamist movements and quietly work under the auspices of the regime to pursue fundamentalist social objectives. Conversely, political Islamists and activist salafis engage in both political and military means to transform society. However, given that participation in armed conflict precludes quietist Salafism, it is the choice of the author to instead use the term “traditionalist Salafism”. Whereas salafi-jihadism is a nominally modern phenomenon, gaining prominence during 1970s and the Soviet-Afghan War, quietist or traditionalist Salafism date back to the teachings of Jamal al-Din al-Afghani and Muhammad Abdu, two the 19th century’s most prominent Islamic scholars.

2 While prominent traditionalist tenets such as irja’ and wali al-amr date back to the 7th century, the Madkhalis are a modern movement. Their spiritual leader, Rabi’a al-Madkhali did not rise to prominence until the 1980s and 1990s, when he became an outspoken critic of the Muslim Brotherhood and Saudi Arabia’s Sahwa movement, political Islamist movements calling for reform and threatening to ignite fitna in the Kingdom. However, the term irja’¸ as used in this Telegram post, refers to a longstanding traditionalist tenet of postponing or putting off contentious issues which might instigate fitna. Additionally, while this salafi-jihadi channel uses the term kharaji, or extremist, ironically, he is employs it as an added layer of condemnation, suggesting that Madkhalis perceive Omar al-Mukhtar, the lionized anti-colonial freedom fighter and father figure of modern Libya, as an extremist.

3 Salafi-jihadis often refer to the Tripoli-based Government of National Accord as the “Frigate Government”, a mocking term referencing the GNA’s original confinement to a naval base in Tripoli due to security concerns.

4 This Telegram channel specifically uses the Arabic term “taghout”. This term translates to “tyrant”, but it is particularly common within the salafi-jihadi vernacular.

i درنة ترد بعزها بإذن الله, January 23, 2019, 08:01.

ii جلاء ميديا, October 5, 2018, 11:08.

iii واقع ليبي, October 16, 2018, 18:39.

iv من 01 إلى كل الوحدات, January 8, 2019, 12:12.

v مازلنا على العهد, January 8, 2019, 04:39.

vi فوارس برقة وليبيا, November 28, 2018, 16:02.

vii درنة ترد بعزها بإذن الله, October 15, 2018, 18:07.

viii من 01 إلى كل الوحدات, January 22, 2019, 09:04.

ix واقع ليبي, November 13, 2018, 09:38.

x من 01 إلى كل الوحدات, January 20, 2019, 14:58.

xi من 01 إلى كل الوحدات. February 4, 2019, 16:30.

xii Reuters Dernia, January 14, 2019, 18:22.

xiii أندياترو.R., February 1, 2018, 08:29.

xiv كشف الحقائق, September 3, 2018, 17:55.

xvi رجال بنغازي, December 28, 2018, 14:05.

xvii من 01 إلى كل الوحدات, November 28, 2018, 07:41.